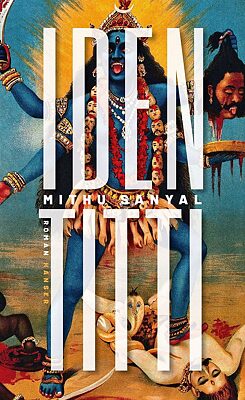

Mithu Sanyal

On the merry-go-round of identity debates

Identity policy can be difficult, polarising and confusing. Incorporating lots of topical allusions to academic life and popular culture, cultural scientist and writer Mithu Sanyal successfully presents the struggle for identity and the authority to define it in her tongue-in-cheek debut novel.

By Helena Matschiner

On her blog Identitti, student blogger Nivedita publishes excerpts from her ongoing inner dialogue with the Hindu goddess Kali. The blog’s subjects draw on the contents of the seminars of Professor Saraswati – an internationally-renowned star professor of postcolonial theory.

Woke Professor Saraswati strongly advocates the self-empowerment of black, indigenous and other people of colour and attracts considerable attention when, in her first seminar, she tells all the white students to leave the class. Later, she explains that her aim was to make the remaining students feel what it means to enjoy privileges on account of their skin colour, presumably for the first time in their lives. For Nivedita and her fellow students, Saraswati soon becomes more than just a lecturer. She makes them sit up and think and changes their self-perception, becoming their life coach and role model. Through her influence, Nivedita becomes an out-and-proud person of colour.

Race is a story

And then something happens that is not supposed to happen. It emerges that Saraswati’s real name is Sarah Vera Thielmann and that she is as German as Germany’s deposit-bottle scheme. The subsequent storm of protest on social media is directed not only against Saraswati, but also Nivedita, who, on the day of the revelation – about which she knew nothing at the time – had praised her professor to the hilt in a radio interview. Nivedita moves in with Saraswati for a while to escape the hostility. She also feels that Saraswati owes her an explanation.But the professor proves impervious to all accusations. Like gender, she says, race has to be seen as a social and political construct. That is the premise of post-colonial theory. In passing herself off as someone else, all she was doing was taking this idea to its logical conclusion. Feminist and anti-racist theory aims to gain the power to define oneself. “How can you say I don’t have the power to define myself?” she asks her critics.

Caught in the limbo of identity discourses

In the weeks following this supposed scandal, a small community with a shared destiny forms in the sweltering summer heat of Saraswati’s apartment, the “bird’s nest” high above the street where they co-habit for the sake of convenience. Their discussions are intensive, but circular, trapped in the “eternity of an echo chamber”.The outside world enters in the form of critics demonstrating outside the house and social media posts. The revelation rekindles a heated global debate about identities and who has the right to define them, about privileges and crossing red lines. The more heated the debate, the more tiring it is. “I’m giddy as hell,” posts an exhausted social media user.

A plea for love

As a cultural scientist, the author lets leading representatives of postcolonial theory have their say. But rather than providing any answers, the book gives the impression that all the questions are justified. Besides Nivedita’s blogs, the narrative is interspersed with fictional tweets of real public figures and cameos of well-known journalists, which has a beneficial effect on the reading experience in view of the sometimes rather redundant discussions.Tongue-in-cheek as the presentations of the fan cult surrounding Saraswati and her vehement critics may be, the author does not deny the significance of engaging in discussions about identities. But she also reminds us that in the end, what matters is not haggling over words but taking a united stand against society’s shift to the right. The novel ends with a plea for love by American writer James Baldwin, who once said that we can disagree and still love each other unless your disagreement is rooted in my oppression and denial of my humanity and right to exist. Or, in Kali’s word “Let love flow like a river”.

Mithu Sanyal: Identitti

München: Carl Hanser Verlag, 2021. 432 p.

ISBN: 978-3-446-26921-7

You can find this title in our eLibrary Onleihe.