Cherrypicker

All this violence

Anne Rabe’s remarkable family novel impressively traces a history of violence in (East) Germany. It stretches from the Nazi era to the present day.

By Michael Krell

Mere fragments

Stine did not experience the “real socialism” of the GDR in her lifetime, but the regime shaped the lives of her parents and her beloved maternal grandfather, Paul Bahrlow. His life story, researched by Stine in the course of the book, forms the book’s central narrative thread. Up to the end of his life, grandfather and granddaughter share a close relationship, but Paul’s past remains largely hidden from Stine. He only tells her about his life in fragments, so that Stine is left with some questions after his death: Why did he keep silent about the National Socialist era? How far did his love for the socialist regime extend? The research into Paul’s past is the glue that holds Anne Rabe’s fragmentary narrative together and gives the book the dense tension that makes it stand out.Pervasive cruelty

Stine’s experiences of violence, which occur again and again over decades and in the most diverse forms, are the central theme of the book. One of its most important statements is that the structures of violence that shape the system in a dictatorship like the GDR have an effect even in the smallest niches of the private sphere. Stine’s mother in particular, a staunch communist and teacher, is capable of the worst cruelties in the upbringing of her two children; due to his passivity, her father – with one exception – becomes an accomplice. Things are also rough at school. The “Nazis,” xenophobic idiots, not only torment one fellow pupil with a migration background or supposedly different-thinking “ticks.” They also spread fear and terror without ideological motivation, just for the fun of it – in part because they are allowed to operate in a kind of right- and morality-free space.Seeking and finding happiness

But it’s not only others – Stine’s own self-injurious actions, or the break in friendship with Ada provoked by her and the lack of empathy for her experiences of violence, make clear how deeply the system is also in her, in this first post-reunification generation. This indifference to her own and others’ suffering seems almost pathological, although she is able to detach herself from it later after the birth of her first child.She does not quite succeed in turning away from her past, as painful as it may have been. Unlike her brother (“my partner in crime, my best friend, my brother animal”), who moves far away from northwest Mecklenburg, she remains in the East. But then the horizon expands and the story comes full circle. It ends as it began – with a holiday, only this time it is Stine’s holiday with her own two children in Sweden. Non-violent and without ideological mendacity. The possibility of happiness.

Plea against indifference

Despite the non-linear structure, the novel reads quite smoothly, the characters are interesting and believable, and protagonist Stine, this brave and upright woman with all her imperfections, grows on you. Precisely because it presents so much harrowing brutality, the book serves as a powerful plea for a more social and less indifferent community. Ideally, it can thus make an important contribution to the discussion about how to deal with East Germany’s past.

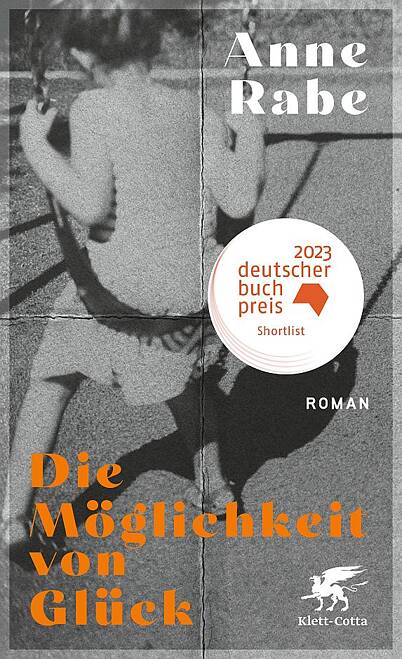

Anne Rabe: Die Möglichkeit von Glück. Roman

Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 2023. 384 p.

ISBN: 978-3-608-98463-7

You can find this title in our eLibrary Onleihe.