Climate change in Northern Quebec

“Everything is less predictable now”

Promoting and protecting the art and culture of the Inuit of Nunavik is the mission of the Avataq Cultural Institute in Montreal, the Canadian partner in the residency project “The Right To Be Cold” of the Goethe-Institutes of Norway, Finland, Russia and Canada. In this interview, artists Olivia Lya Thomassie and Nicolas Pirti-Duplessis, who both work at the institute, talk about their life between two cultures, the impacts of climate change on living conditions in the north, and their work at Avataq.

By Caroline Gagnon

Our goal is to contribute to the establishment of a network of museums or transmission centres dedicated to Inuit culture.

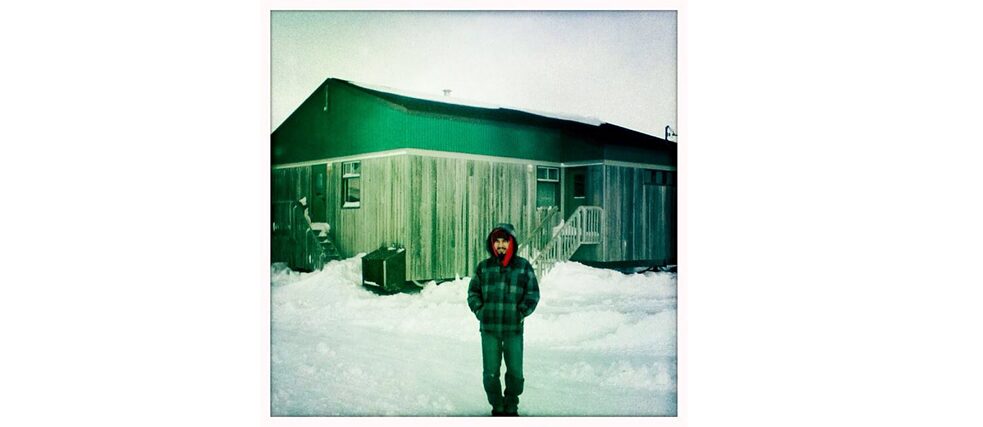

Nicolas Pirti-Duplessis

Nicolas Pirti-Duplessis

| © Avataq

Nicolas Pirti-Duplessis I am originally from Akulivik. My father is from Quebec and my mother is Inuit, hence my last name Pirti-Duplessis. Both of them are teachers, and I became one too. I am also a translator — I am trilingual — and a musician. My band is called Arctistic. I like the play on words in Arctistic, because my village is at the bottom of the Arctic Circle and the album is an art project. I’ve been working at the Avataq Cultural Institute as an information officer since 2018. Before that, I worked in the field of cartography. I travelled to eleven communities in Nunavik and conducted interviews with hunters and elders to ensure the accuracy of the toponyms collected in the 1980s and to make corrections, if necessary. I discovered many hunting sites and the territory of Nunavik, which includes fourteen communities, plus the community of Chisasibi, which is in Cree territory. That makes fifteen in all. These communities come under the Makivik Corporation, which represents the Inuit in their relations with the governments of Quebec and Canada. There are 14,000 Inuit in Quebec and 67,000 in Canada.

Nicolas Pirti-Duplessis

| © Avataq

Nicolas Pirti-Duplessis I am originally from Akulivik. My father is from Quebec and my mother is Inuit, hence my last name Pirti-Duplessis. Both of them are teachers, and I became one too. I am also a translator — I am trilingual — and a musician. My band is called Arctistic. I like the play on words in Arctistic, because my village is at the bottom of the Arctic Circle and the album is an art project. I’ve been working at the Avataq Cultural Institute as an information officer since 2018. Before that, I worked in the field of cartography. I travelled to eleven communities in Nunavik and conducted interviews with hunters and elders to ensure the accuracy of the toponyms collected in the 1980s and to make corrections, if necessary. I discovered many hunting sites and the territory of Nunavik, which includes fourteen communities, plus the community of Chisasibi, which is in Cree territory. That makes fifteen in all. These communities come under the Makivik Corporation, which represents the Inuit in their relations with the governments of Quebec and Canada. There are 14,000 Inuit in Quebec and 67,000 in Canada.Olivia Lya Thomassie I am originally from Kangirsuk, in Ungava Bay. It’s about the same latitude as Akulivik, where Nicolas is from, but Nicolas’s village is along the Hudson Bay. I am also of mixed race. My father is a Quebecer from Trois-Rivières, and my mother is an Inuk from Kangirsuk. I am an artist, I have made short art videos with Wapikoni mobile and I am interested in beading. I also do a little bit of theatre. The play I’m in now, Aalaapi, will be presented at the Festival TransAmériques.

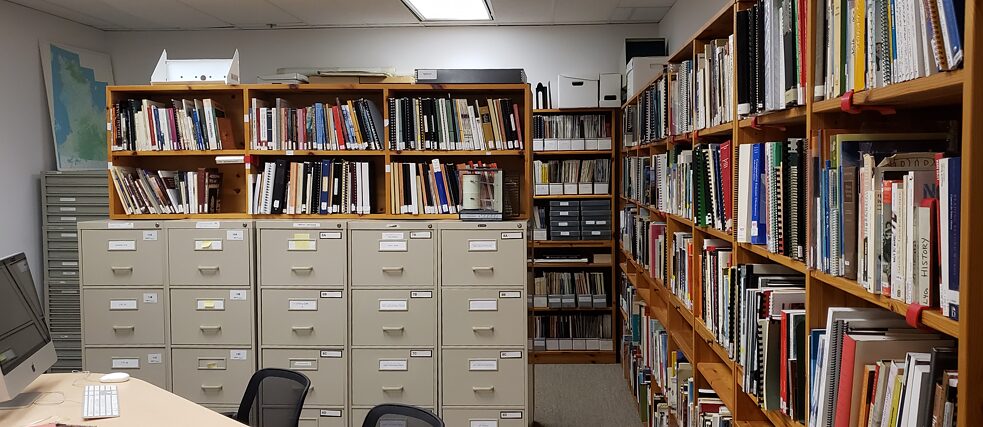

Nicolas Pirti-Duplessis The mission of the Avataq Cultural Institute is to protect and promote the language and culture of the Inuit of Nunavik (Northern Quebec). The institute includes different departments: archaeology; local cultural committees; research, libraries and archives; museology; Inuktitut language; communications and publications; arts secretariat. The head office is located in Inukjuak, a village on the Hudson Bay. There are three full-time employees. We also have an office in Montreal, where we keep the archives and the objects that have been entrusted to us. For instance, we have many interviews with elders from the 1950s and 1960s. Our goal is to contribute to the establishment of a network of museums or transmission centres dedicated to Inuit culture. We are mainly active at the local level, but we also participate in international projects.

© Avataq

Olivia Lya Thomassie I work in the Aumaaggiivik department, the Nunavik Arts Secretariat, within Avataq. Our mandate is to support Nunavik artists. We have a grant program, but we also help artists write grant applications at the federal, provincial and municipal levels. We promote events by Inuit artists, and every month we feature a Nunavik artist on our website. I interview the artist of the month and write a text in English, which is translated into French and Inuktitut. We also organize events, such as recent live shows on Facebook.

© Avataq

Olivia Lya Thomassie I work in the Aumaaggiivik department, the Nunavik Arts Secretariat, within Avataq. Our mandate is to support Nunavik artists. We have a grant program, but we also help artists write grant applications at the federal, provincial and municipal levels. We promote events by Inuit artists, and every month we feature a Nunavik artist on our website. I interview the artist of the month and write a text in English, which is translated into French and Inuktitut. We also organize events, such as recent live shows on Facebook.

The Ice Breaks

The theme of The Right To Be Cold project is climate change and its impact on the circumpolar regions. You both come from these regions and you have the opportunity to go there regularly. What do you see? How is climate change being felt in your communities?Olivia Lya Thomassie I’ve discussed this issue with many people in my community, including elders. Everything is less predictable now as far as the weather is concerned. What struck me are hunter and fishermen accidents. The ice breaks more and more often when they travel by snowmobile.

Another change is that materials are no longer reused as they were before. In the past, seal or caribou skin was used to make kayaks or sleds. The animal that was killed was used to meet different needs. Today, we travel mainly by snowmobile. So we have to bring snowmobiles to our regions or bring in spare parts to repair them. It’s very expensive, and it’s not environmentally friendly.

I met indigenous people from South America who told me about mining projects in their region. Even though the mines are hundreds of kilometres away from the main centres, they impact a whole country, because all the regions are connected by nature, whether it’s rivers or trees affected by mining activity. So it’s a global issue.

I would also add that more and more biologists are coming to the north to study the effects of climate change by taking samples from animals or fish. I’m looking forward to seeing the results of these studies

More Snow than Before

Nicolas Pirti-Duplessis I remember that in the 1990s it was already cold in September. I also remember that on Halloween we had to wear our costumes over our winter coats because it was so cold. Now the cold comes later. We used to be able to go out on the ice on snowmobiles in October, but now it’s more like December. So there’s a time lag of at least two months. Also, in the last few years, there’s been a lot more snow than before. When this snow melts, it floods the village. That’s another problem.I’m not a scientist by any means, but I think the solution must be renewable energy sources. In Kuujjuaq, for example, there is a geothermal power plant. There are also geothermal plants in Iceland. I think that would be a good way to produce electricity with the energy sources we have.

Do you return to Nunavik often?

Olivia Lya Thomassie I try to go as often as I can, but at the moment it’s not possible because of the pandemic. There are a lot of people in the houses and I wouldn’t have room to quarantine. Normally I go two or three times a year.

Nicolas Pirti-Duplessis Airline tickets are very expensive, costing an average of $4,000, but as beneficiaries of the Makivic Corporation, we get a 75% discount. The biggest problem, as Olivia explained, is finding a place to stay. In Kuujjuaq, there is a house for quarantine, but not elsewhere.

The interview was conducted by Caroline Gagnon, Program Curator, Goethe-Institut Montreal.