March 2019

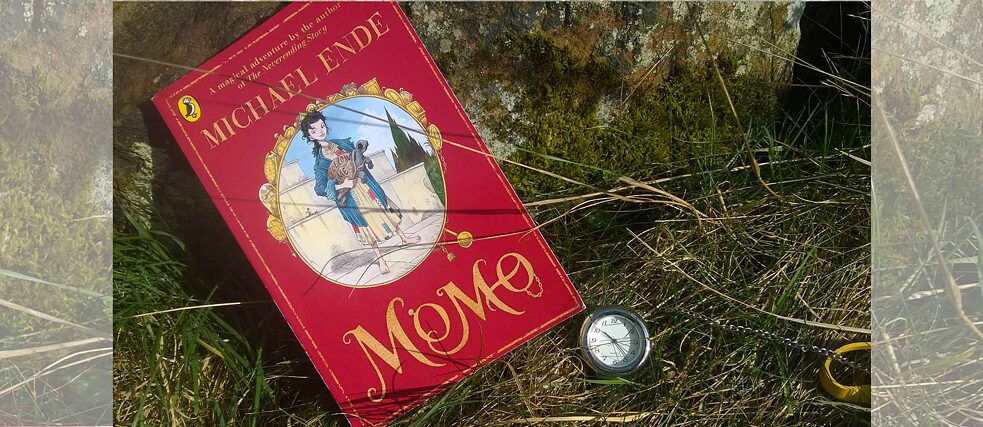

Momo: when time stood still

Unsurprisingly enough, I was an avid bookworm as a child. I still love the magic of children’s books – the way they take stories and their readers so seriously yet with so much lightness. Occasionally as an adult I come across a gem which I wish I had known as a child. If I could gift a bundle of books to ten-year-old me, that parcel would most definitely include Terry Pratchett’s Tiffany Aching series and Michael Ende’s glorious Momo (tr. J Maxwell Brownjohn).

The Tiffany Aching stories (aimed at 9 – 11 year olds) start with the novel The Wee Free Men, in which Tiffany must journey into Fairyland to rescue her brother – and to prevent the elves who have kidnapped him from returning to make people their playthings. The books are more thoughtful than much of Pratchett’s Discworld series, and Tiffany learns along the way about community, responsibility and the immense power of stories.

Like Tiffany, Michael Ende’s Momo seems an unlikely heroine at first – an apparently unremarkable child, but one who, like Tiffany, sees things for what they are. A staple of German children’s literature, Momo deserves a higher profile in the UK. Rich in only one thing – time – Momo lives in a ruined amphitheatre at the edge of a town, a good friend to the neighbourhood’s children and grown ups alike. Slowly but surely, though, Momo’s town begins to change, infiltrated by the surreptitious “grey men” who “were experts on time just as leeches are experts on blood”. Employees of the sinister Timesaving Bank, the men encourage the town’s inhabitants to thriftily save their time, cutting down on daydreaming, visits to lovers, conversations with friends. The more time people save, the less they have, and life becomes ever bleaker and more monotonous. It is up to Momo to venture beyond time in order to defeat the grey men and let the world begin to live again.

Ende, who is better known in the English-speaking world for The Neverending Story, doesn’t share Pratchett’s trademark sense of humour (who does?), but both authors use fantasy exquisitely in order to explore our own reality. Ende’s depiction of a society so focussed on productivity that its people forget how to dream is gut-wrenchingly familiar for adult readers – and the story’s reminder that “time is life itself, and life resides in the human heart” is a message to return to long after the book has been closed.

Philip Pullman once suggested that “there are some themes, some subjects, too large for adult fiction; they can only be dealt with adequately in a children’s book.” It’s a bold claim, but harbours a truth – children’s books like the Narnia series, Pratchett’s Tiffany Aching series and Pullman’s own His Dark Materials trilogy gain their depth and fascination from their exploration of the larger questions in life: where we come from, who we are and what it means to live well. Momo is one of these books – and it deserves a place on the same shelves. Child or child-at-heart, make sure you make time for it.