November 2019

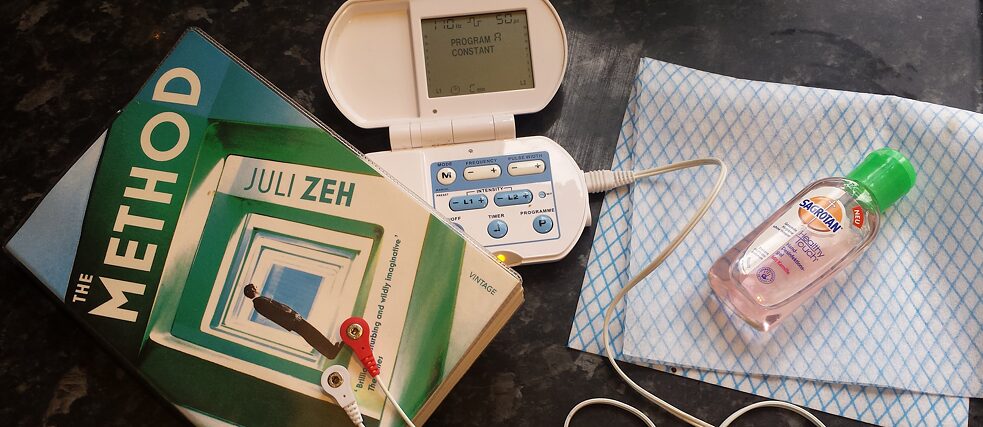

Juli Zeh: The Method

It’s become commonplace keenly espoused by earnest young men with beards that sales of dystopian novels surged in the months after Trump was elected. As a bookseller at the time, I can attest to the truth of this – although the bearded young men tend to forget that the filming of a number of these novels around the same time might also have been a factor. One such book was Dave Eggers’ The Circle, a tech-based novel set only very slightly in the future. In it, the eponymous Circle has monopolised the web, swallowing Google and Facebook, and its vision for society leaves the reader asking where transparency ends and surveillance begins.

Perhaps you enjoyed The Circle. Perhaps you thought it was a bit heavy-handed. Perhaps, like me, you felt it could have done with being 100 pages shorter. Either way, you should definitely add Juli Zeh’s The Method, translated by Sally-Ann Spencer, to your TBR pile. The Method is set in Germany in the 2050s. The common cold has been eradicated for decades, any failure to take precautions against disease is a crime and it has been scientifically proven that “individuals with non-complementary immune systems can’t fall in love.”

Mia Holl falls foul of the Method, as the state calls itself, after her brother is convicted of a crime she’s convinced he didn’t commit. What starts as a petty offence – the failure to provide her monthly urine samples and sleep pattern data – turns into a radical questioning of the state she had always believed in. Like The Circle, Zeh’s novel portrays a system “that believes total transparency exposes only those with something to hide”. The Method takes as its starting point however a truly utopian idea – who wouldn’t want to live their life a stranger to fear and pain? According to the novel, it isn’t what we believe which can lead to evil but rather how zealously we hold to and defend our convictions.

Where The Method really comes into its own though isn’t through its ideas but through its characters and their sparring, flirting, loving relationships, which are always believably complicated. All of the characters (with the possible exception of Mia’s defence lawyer, Rosentreter) are seductive in their own way, with Mia’s reflection on her brother applying equally to Mia’s conscientious judge, or to the charismatic proponent of the Method, Heinrich Kramer, or indeed to Mia herself: “She would think, though she never said so, that Moritz, although quite probably a little unhinged, was someone you couldn’t resist.”

For all that dystopias are often based around ideas of science fiction or alternate history, their depictions of people are often steeped in a depressing amount of realism and rationalism. The Method gains depth, warmth and redemption through the rich imaginative realm which Moritz and Mia share. If the book is a plea for empathetic imagination over fanatical rationalism, it is itself its most convincing argument.

Reserve your copy of the book in our library today!