Series: German filmmaker in India (2)

A Repository of Salvations

In this present series we examine a series of films produced by German authors in India. The series identifies these as being useful examples of a ‘visitor-film’. The second article obeserves Franz Osten’s Shiraz.

Franz Osten’s 1928 classic – the second part of a trilogy of mythological epics he produced in the 1920s as part of his collaboration with Himansu Rai – achieves a singular confluence: it renders the legend of the creation of Taj Mahal in terms that are purely empirical, purely chronological. This achieves a curious effect, for when the apocryphal story is rendered in terms that are scientific and banal, the romance inherent in it becomes even more pronounced.

Restoration finds itself, especially in the present day and context, as an act that intersects spiritually with another: the erection of a monument. In so far as one may consider the desire to install a monument as an act that calcifies – that renders eternal – the essence of a memory, the restoration of a filmic object too can harness its inherent energy and project it into an infinite future. ‘These’, says Shiraz, as he presents Khurram, the Emperor, with a model of the Taj Mahal, ‘are my memories rendered in stone’ (and similarly, Tagore declared, as only a poet can, the great monument to be: ‘…a tear on the cheek of time’) – the parallels with film restoration are obvious, but worthy of exploration. And while restoration provides the ghost of the film with a new embodiment, its true séance – the force that truly induces in it a new consciousness – is the musical accompaniment. A number of discussions abound in the fields of silent film preservation and presentation around the subject of the musical accompaniment: its ethical implications, its position in the artistic hierarchy and a pending, due recognition as an autonomous form.

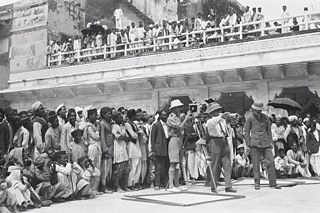

For one, in most cases, the director of the film, or its writer, is dead. The composer of the score must therefore assume the status of the medium – if not to exactly speak on behalf of the departed, then atleast, not in lieu of them. The assumption of the status of a medium is of course, akin to an erasure of the self: the medium is expected often to willingly submit to an annexation of her own being, her identity and her shape by her client, the recipient of her assistance. It is therefore interesting that in their presentation of Shiraz in New Delhi, the organizers (the British Film Institute) placed the musicians in front of the screen - directly under a spotlight. Whether this is due to the demands of the architecture or the celebrity of the composer (Anoushka Shanker), one can speculate. Insofar as this strategy yields a curious, essential effect of distantiation, a nearly auto-reflexive revelation of the construct behind the exhibition of a silent film to a local audience not accustomed to an event of this nature, its success is undeniable. The layout of the screen vis-à-vis the group of musicians is revelatory and explicit in another regard: the musicians assume, as if to say, the avante garde – they seem to, like carriage drivers with reins in their hands, lead the film to a waiting, eager audience. Through their accompaniment – or perhaps, through their headship – a final salvation of the night becomes possible: of the film itself.

It helps that Shiraz is a significant title too - notwithstanding the various poetic implications it yields by being a film about faith, harmony, romance and finally, homage and resurrection - for it displays, much like Osten’s 1929 masterpiece, A Throw of Dice, an interesting, Lang-ian habit: to cultivate a realm of ancient myth through the effects of modern science (tidbit: Lang and Osten did share a cinematographer in Josef Wirsching). In his 1929 masterpiece, A Throw of Dice, Osten chooses to depict the central, microcosmic event of the Mahabharata, the gambling match, as an event whose outcomes are influenced not by the arbitrariness induced by luck or mere chance, but instead, by scientific, completely empirical maneuvering (the scheming villain induces in the instrumental dice an unnatural tilt by tampering its internal mechanism).

The history of cinema features a considerable tradition of films produced by individuals who travel to a land not their own – an ‘alien’ country, a ‘foreign’ landscape – to record local ‘reality’. Over the years, however, this tradition has been subjected to immense scrutiny by commentators, who have identified it in strains that mimic imperialism, exoticism, primitivism and also, pure fantasy. ‘How’, the critics of these films ask, ‘can an individual not acquainted with a land be entrusted with the task of translating its basic truths?’

In this present series, entitled, ‘A Procession of Masks’, writers from Lightcube, a film collective based out of New Delhi, examine a series of films produced by German authors in India. The series identifies these as being useful examples of a ‘visitor-film’ that perceives the subject of its study through a system of dignity, empathy and curiosity. The four articles contained in the series explore different mechanisms by which to locate value and merit in the films produced by ‘outsiders’ – as also, to look for new ways in which to talk of these titles. The series includes discussions of three primary examples: Werner Herzog’s Jag Mandir (1991), Franz Osten’s Shiraz (1928) and the films of Paul Zils.