The fall of the Berlin Wall

How the GDR perished in "Burgfrieden

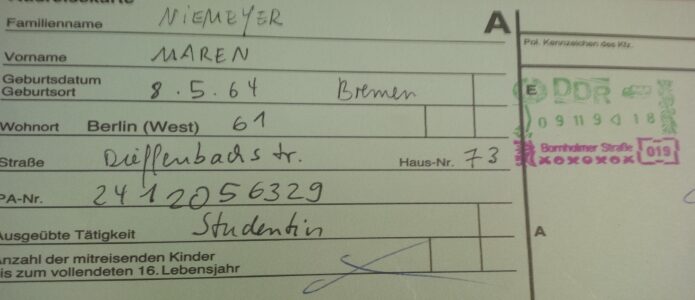

Although back then a young radio journalist from West Berlin, the current director of the Goethe-Institut Thailand, Maren Niemeyer, experienced the night of the Fall of the Wall by chance in East Berlin on November 9, 1989.

Invited by DEFA director Heiner Carow, she attended the premiere of the feature film “Coming Out” at cinema “Kino International” with her boyfriend. Since the premiere party happened to take place in proximity to the border crossing Bornholmer Straße, Maren Niemeyer had the historic fortune to be present when the wall came down and the border was opened for the first time for everyone from East Berlin.

20 years ago, she wrote down her impressions of this exceptional night in an article for the daily newspaper “Die Welt”.

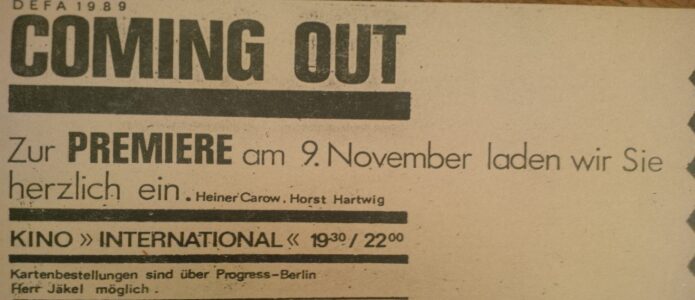

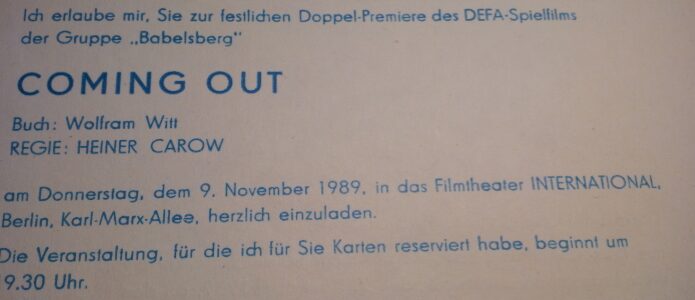

On 9 November 1989 Heiner Carow planned on celebrating the premiere of "Coming Out"—but something came in between

The premiere was scheduled for 9 November. The film was called "Coming Out". It was about the self-discovery of a homosexual teacher in the GDR. Heiner Carow’s film was set to premier in the film theatre "International", which had hosted the premieres of the DEFA film studios, at half past seven in the evening. However, a few streets away and only one hour earlier, Günter Schabowski had announced the GDR’s political “Coming Out”, reading off his legendary sheet of paper. The explosiveness of Carow‘s "Coming Out" had been considerable up to this hour, and so it still seemed to those involved: it was the GDR’s first gay film. After seven years of being banned from his profession, Carow, who was a dissident of the SED and the director of the film adaptation of Plenzdorf’s "Die Legende von Paul und Paula", was allowed to make another feature film. It was a DEFA project eagerly awaited in the East. Carow had visited us several times for research talks in West Berlin.

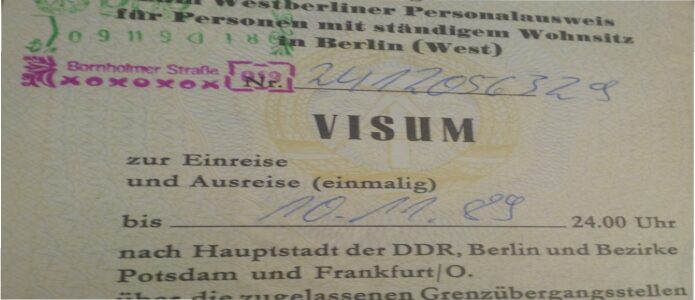

At 6 p.m. everything is as usual at the border crossing Bornholmer Straße. It is going to be late. We therefore enter the date November 10 in the "Departure" section, and the border guards routinely issue the appropriate “visa” as an "annex to the West Berlin identity card". The customs and currency declaration has the no. 2455198. Winding corridors created by check-in barriers, small hatches into which the mandatory exchange fees are handed in and travel documents are handed out. Behind each customs official there is a second one, who carefully examines the process and the travellers entering the country. Upturned military collars in the cold of November.

The cinema "International" is vibrating with expectation. The day before, the SED Central Committee had resigned just like the government before, and Walter Janka’s memories were read aloud in the Deutsches Theater and live on GDR radio—the ice melts quickly. And now a gay film. In the leading roles, the already popular actress Dagmar Manzel as well as the newcomers Matthias Freihof and Dirk Kummer. A few openly homosexual guests show up — something unheard of on an official occasion in the GDR. Still a little shamefaced, wearing the hats of the capital’s intelligentsia’s cultural communards. A scarf here, an earring there, and the scent a little less masculine.

The film receives enthusiastic applause, probably less because of its solid, unagitated narrative style. The signals of truthfulness that Carow sets are euphorically welcomed. The artists present applaud their moment of being on the verge of change, which they manifested with the large demonstration on 4 November and which Carow now crowns with images of cultural narrowness and its overcoming. Look at us, we too can show everything now, and we can do much more. Moved, Carow receives the ovations, each “bravo” an act of rehabilitation for the 60 years old SED critic, the unfaithful faithful, who always remained loyal to the country and the party and whose recalcitrance his authorities let him in return get away with.

In one of his shooting locations, a gay bar in Prenzlauer Berg, a 15-minute walk from Bornholm bridge, Carow invites the core group of guests to the premiere party. Meanwhile, news agencies are already sending the dream fabric around the world: The Berlin Wall is falling. An illegal taxi takes us out of the two-hour film screening, that no news could penetrate, to the party, which is celebrating something that will never happen again: a national GDR film premiere. The party is wild—nobody knows what is going on outside the pub door. Does nobody know or does nobody just want to know?

But the new reality out there is too monstrous to leave the islands of yesterday alone. It storms in in the shape of a fuzzy-haired man in his mid-thirties. "They opened the wall!" Facing the speechless crowd aligned at the bar in front of him, the half-opened pub door behind him, the uninvited guest waits for the effect of his words. But no one believes him. "Grab a drink, it’ll be alright", the innkeeper reassures him. The man hurries away, shaking his head. Only a second appearance of this kind makes the party crowd leave the pub and look for themselves.

Even through the small side streets an endless queue of Wartburgs and Trabbis moves towards a destination, which passers-by shout out loud from the rolled-down side windows of their cars: "To the bridge! The Bornholmer Straße crossing is open, we’re driving to the other side." The party quickly retreats back into the pub. Magnetised, the guests face Carow, sending frightful glances at the door. Who and what will, in this eerie night, want to find their way in? A different director is going to take over, a different film is going to play, everyone can feel it. General discussing of the events begins. So that’s how it is. The Wall is shaking. The Wall is collapsing. What does that mean? What is going to happen? What is going to become of the small, grey country; of its cultural protagonists, of me? For the first time, the word of the “winners” comes up. "Yes, there you have it—yes, you, from the West—you’ve made it, then!"

The rumour, the agitation results in a defiant decision: We won’t change sides, we won’t even go out. We will stay right here. We’ll close the door and open our own GDR. Whatever happens, the premiere goes on. Goes its own way. The leading actor affirms it, the film critic present, the leading actress, the director himself. Those who find words again, express fears. The film critic Margit Voss: "It’s all going way too fast." Leading actor Dirk Kummer: "Man, I hope they don’t shoot!" Heiner Carow encourages his winter guests: "Everything will take a lot of time, no need to hurry." Only scriptwriter Wolfram Witt expresses hope: "Maybe now I can finally get the meds I so urgently need." Witt is seriously ill.

We couldn’t take it any longer. We left. Our party was taking place at the border. The midnight stream of people, which was flowing in a dream through what is usually at this time a completely extinct "capital", pushed us towards Bornholm Bridge. The inconceivable was happening: Speechless, almost motionless, the border guards let the car traffic pass by. Through a wide aisle, exuberant people pushed their way past their guard houses from East to West, from West to East. The turnpike was lifted, and it was hard to imagine that it would ever come down again. Berlin, the separated couple, was literally rushing towards each other physically—more than once we had trouble explaining that we crossed the disempowered border strip from the east, but not as Easteners.

For about an hour, the unimaginable let us forget what had brought us to East Berlin that night. Then our curiosity drove us back to Carow‘s premiere party. In fact, everyone had stayed in the pub. Someone had turned off the music. Quietly, in small groups, partly in tears, they were still discussing the new situation. Nobody was interested in our descriptions of the scene of the opening of the border. "Now we have fallen from the branch we sawed for 40 years", East Berlin comedian Peter Ensikat would say on stage the next day. "Coming Out"—the film title that was conceived to convey a certain meaning and had actually materialised that night to the dismay of our hosts and had transformed our GDR visas into tickets for a closing night, starring perplexed performers. The pub in which we experienced the saddest celebration of unity of that night, was called “Zum Burgfrieden“, “The Truce”, by the way.

The film critic Margit Voss—being the one to encourage Carow to look into the film’s theme in the first place—now works for Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk and "Neues Deutschland".

Screenwriter Wolfram Witt was later accused of doing some legwork for the Ministry for State Security and withdrew from public life.

Dirk Kummer went to Switzerland, dropped out of acting school and now lives as a director in southern Germany.

Heiner Carow died in February 1997. After the fall of communism, he was unable to build on his success in the GDR.