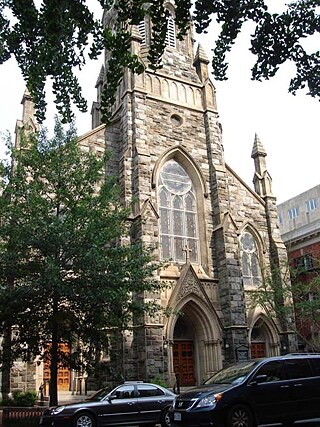

St. Mary Mother of God Roman Catholic Church

German Roots in DC

-

St. Mary Mother of God Roman Catholic Church, August 2010.

-

St. Mary's Church and Parochial School, October 9, 1949, as photographed by John P. Wymer.

From The United States Catholic Magazine, 5 (1846) p. 226, as reprinted in History of St. Mary's Church of the Mother of God Washington, D.C. 1845-1945. Second Edition, pp.16-17. (courtesy of HSWDC)

New German Catholic Church—The cornerstone of the new church intended for the use of the German Catholics under the pastoral care of Rev. M. Alig of this city (Washington) was laid yesterday, March 25th, by the Most Rev. Archbishop Eccleston with appropriate solemnities in the presence of an immense body of people who witnessed the ceremonies. A very large procession accompanied by the German band moved along Pennsylvania Avenue from St. Matthew's Church passing into Four and a half street and thence to the site of the church of St. Mary Mater Dei which is situated on Fifth Street between G and H Streets. The procession formed at the German chapel on Eighth Street and marched thence to St. Matthew's Church. When the procession arrived at St. Matthew's, there was a considerable increase of its number. As it passed along Pennsylvania Avenue, we noticed—

- The German band.

- The German Beneficial Society, two and two, wearing white rosettes and bearing a handsome banner with a representation of the merciful Samaritan.

- The German Male and Female Society: the males wearing red sashes, the females dressed in white with wreaths of flowers on their heads, preceded by their Pastor, the Rev. M. Alig.

- The Washington Benevolent Society, two and two, bearing their handsome green silk banner and each member wearing a green badge.

- The Rev. Messrs. Flannegan and Ray of Georgetown, the Rev. Messrs. Donelan of Washington and several of the clergy of Baltimore in their clerical robes.

- A numerous body of Germans and citizens walking two and two.

Dedication-The new Church, for the German Catholics of Washington city, was blessed by the Most Rev. Archbishop on the 7th of September under the invocation of the Mother of God (Mater Dei).

From the Evening Star, 26 July 1890:

CATHOLIC SOCIETIES AT CORNERSTONE LAYING TOMORROW

The ceremonies connected with the laying of the cornerstone of the new church edifice of St. Mary's Catholic Church will take place tomorrow afternoon beginning at 4:15 P.M. Bishop A. A. Curtis of Wilmington, Del., will officiate and will preach the English sermon. The Rev. R. Preiss will preach in German. The procession will move at 3 o'clock from the corner of 16th Street and Massachusetts Avenue Northwest. The route will be down 16th Street to H Street, to Jackson place, to Pennsylvania Avenue, to 5th Street, to Church.

From the Evening Star, 28 July 1890:

With imposing ceremonies and in the presence of a great concourse of people, the cornerstone of the new church edifice of St. Mary's parish was laid yesterday afternoon. The location of the new church building, on 5th Street, between G and H Streets N.W., was the central point about which the people began to gather long before the hour assigned for the ceremony. A covered platform was erected over the foundation in the front portion of the building, and this was occupied by the clergy and laity who had been invited to witness the ceremonies. At 3 o'clock a procession was formed at Scott Circle of the Catholic Societies of the city. Under the direction of the chief marshal, Mr. J. H. Buscher, and to the music of the brass bands, the line of the parade moved over the route in the order which has been printed in the EVENING STAR. The fine appearance of the marching columns, which comprised some twelve or fifteen hundred men, was commented upon by the spectators who assembled along the route to witness the display.

CEREMONIES ON THE SITE

When the procession drew near the church site, the clergy attended by acolytes came out from the adjoining residence of the pastor, Father Glaab, and proceeded to the platform. … The ceremonies were conducted by Bishop A. A. Curtis of Wilmington, Del., and after the foundation walls had been blessed and sprinkled with holy water the stone was blessed and set in place. The trowel used was the one that figured in the ceremony forty-four years ago, when the cornerstone of the old church was laid. It is owned by Urban Geier, a member of the church. The articles placed in the copper box sealed in the cornerstone included copies of several English and German newspapers, foreign and American coins, including United States coins of every denomination, photographs of Father Glaab and the church building committee and a written history in brief of the parish.From The Catholic Mirror, 4 July 1891

ST. MARY'S GERMAN CHURCH-THE DEDICATION CEREMONIES

… The German Catholics have a right to feel proud of their new Church, for it is among the handsomest of the many beautiful Church edifices of the city. …In architecture the new church is pure Gothic, built of Potomac bluestone with Ohio sandstone for trimmings. The Gothic style has been closely followed thru-out, and a graceful high tower gives the outside of the building an imposing appearance, while no less attention has been shown in the interior arrangements, which are almost perfect in detail, and number some genuine treasures in foreign art which were imported at great expense. The stained glass windows are from Munich and are the finest with perhaps the exception of those in the Catholic University in the city. Those near the entrance on the south side represent Sts. Aloysius and Michael. Others on the same side contain representations of Sts. Theresa and Elizabeth, St. Boniface performing Baptismal rites, the Assumption and the Resurrection. The sanctuary windows contain representations of the four Evangelists, while on the north side of the church appear delineations of the apparition to Mary, the Annunciation, St. Joseph's worship, and Sts. Peter and Paul. The baptistry is lighted by three smaller windows, decorated with a representation of Christ's baptism, the angel and Tobias, and a Guardian angel and a child. One large and several small windows in the gallery complete the natural lighting facilities of the church.

The stations of the cross are beautiful specimens of bas-relief work and come from Vienna. The altars are of Italian marble of exquisite design. The pews are of polished oak and of elegant design.

John Phillip Wymer, Photographer

About John Philip Wymer

(October 19, 1904 - January 12, 1995)

From an article by Charles Paul Freund, "Photo Synthesis: Midcentury Washington from a Man on the Street's Capitol View," Regardie's, May 1986, pp. 56-59

One weekend morning in the spring of 1948 a resident of Cleveland Park swung out of bed and embarked on a mission he'd been mulling over for some time: capturing Washington. John P. Wymer was no general; he was a statistician at the nearby Bureau of Standards. But he was a methodical and remarkably single-minded man, and by the time he was done Washington had become his in ways that such besiegers as Admiral Cockburn and Jubal Early could never claim.

Wymer's idea was to make a photographic record of Washington, all of it, neighborhood by neighborhood, virtually block by block. The project took him until 1952-four years of weekends and vacations. In the process he snapped about 6,000 black-and-white photographs, discarding a third of them and pasting the rest into some 50 photo albums. Washington has inspired a number of large-scale photographic projects, both amateur and professional, but Wymer's 4,000 images make up the most extensive and wide-ranging one-man effort that has yet surfaced.

Wymer carefully grouped his pictures by area; he split the city (omitting the suburbs altogether) into 57 sections that were keyed to a map he created for the purpose. Each area is introduced by a painstakingly typed descriptive and historic preface and features "sample blocks" (the statistician's mind at work). Every shot has a short typed caption pasted under it, identifying it and, in most cases, giving the date Wymer photographed it.

Why'd he do it? Essentially because it was there.

"I thought it would make a nice hobby for me," says Wymer, who's 81 and still lives in Cleveland Park. He was neither an inveterate photographer nor an amateur historian. In fact, he isn't even a native Washingtonian; he had come to DC from California 10 years before starting his project.

It was all just a way to pass the time, he says, that "came to me out of my own head."

But if there were a muse of photography, one might be tempted to think of Wymer's project as a classically inspired obsession, for pressed between the photo albums' cheap pages, which are already brittle and crumbling, is a Washington that's been caught in remarkable variety at a singular moment. Wymer's Washington is a far smaller national capital basking in the sun (all of his shots were taken on nice days) just after its explosive World War II growth and just before suburbanization and the aftereffects of school integration altered the city forever.

. . .

Wymer finished the shooting, selecting, cataloging, typing, and pasting in the early 1950s, and then put his giant stack of albums away. Except for a few times when he showed them to interested friends, he rarely opened them again. In 1978 James Goode, the author of Capital Losses and one of the city's premier social historians, was told about them while he was searching for a shot of an all-but-forgotten downtown restaurant. Goode immediately recognized the collection's value as a portrait of a fast-disappearing community. He notified the Columbia Historical Society, and soon afterward Wymer deposited his albums, negatives, and guide map there.