“There was nothing to say”

Bertolt Brecht and the radio

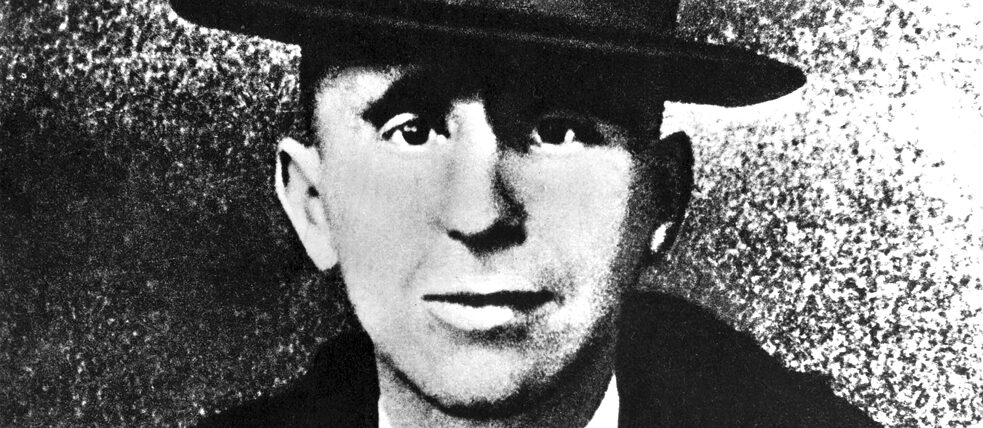

When radio in Germany celebrates its one hundredth anniversary, there is one guest who definitely deserves to be invited to the party: Bertolt Brecht. Andreas Ströhl has written about the role that Brecht played in shaping radio as we know it today.

By Andreas Ströhl

In his speech on “the function of radio” in 1932, Bertolt Brecht demanded that “art and radio should be placed at the disposal of pedagogic aims” [1]. He claimed

“that the application of theoretical insights about modern drama, i.e. about epic drama, could bring about extraordinarily fruitful results in the domain of the radio. […] Furthermore, direct collaboration between theatrical and radio performances could be organized”. [2]

Brecht’s so-called radio theory comprises a handful of notes, newspaper articles and speeches that came about between 1927 and 1932 and in which Brecht outlines his criticism of the present state of radio and his hopes and demands for its future. It was the first time that someone had made political demands that related less to the content of media than to the way in which their channels were wired.

Radio as an intercom system

From a technical perspective, radio could in Brecht’s opinion function as an intercom system. Instead it is a one-way street that permits only passive reception, that is to say distribution rather than communication. And it is precisely this, demands Brecht, that needs to be changed in order for radio to promote sound social development. His suggestion “for the director of radio broadcasting”: “In my view you should try to make radio broadcasting into a really democratic thing.” [3]“Radio must be transformed from a distribution apparatus into a communications apparatus. The radio could be the finest possible communications apparatus in public life, a vast system of channels. That is, it could be so, if it understood how to receive as well as to transmit, how to let the listener speak as well as hear, how to bring him into a network instead of isolating him. […] Radio must make exchange possible.” [4]

Yet nobody apart from those parts of the population who had hitherto been excluded from public life, political decisions and economic participation could have any interest in radio being used to criticize the ruling system.

“The results of the radio are shameful, its possibilities are ‘boundless’. […] If I were to believe that this bourgeoisie would live for another hundred years, I would be convinced that it would drivel on about the tremendous ‘possibilities’ to be found, for example, in radio.” [5]

Provocatively, Brecht asks why in fact his demands for radio are ridiculed as being so utopian: “Should you consider this utopian, then I ask you to reflect on the reasons why it is utopian.” [6]

Radio and coffeehouse music

Brecht gives no indication whatsoever of how this improved dialogic radio could actually be realized in society, however. It’s a classic Catch-22, as better radio could in theory result in a better society, yet different social conditions would be the only way to achieve better radio.In contrast to one-way media such as newspapers, conventional radio and television, dialogic media like letters, the telephone and e-mail have two-way capability. In the latter, sender and receiver switch roles constantly, jointly steer the direction of their communication and also share responsibility for their relationship. This is precisely what Brecht was demanding with his radio theory.

Radio, however, “as a substitute […] for theatre, opera, concerts, lectures, coffeehouse music, the local pages of the newspaper and so forth […] has […] imitated practically every existing institution that had anything at all to do with the distribution of speech or song” [7], yet has created nothing of its own.

“I can remember how I heard about the radio for the first time. There were ironic newspaper accounts about a virtual radio hurricane that was in the process of devastating America. Nonetheless one had the impression that it was not just a craze but something really modern. This impression evaporated very quickly as soon as it was possible to listen to radio here too […] It was a colossal triumph of technology at last to be able to make accessible to the entire world a Viennese waltz and a kitchen recipe.” [8]

Radio – who commissioned it?

The reason why radio is used only as a distribution apparatus rather than as a two-way communication apparatus, which is what really would be desirable, is by no means technological in nature. The radio is an invention “that was not commissioned” and that first needed to “conquer its market” [9]. “It was suddenly possible to say everything to everybody but, thinking about it, there was nothing to say.” [10] The demand for the new technology first needed to be artificially created; it was the “technological development” that drove the social development. “It was not the public that waited for radio but radio that waited for a public”. [11]Radio by the fireside

As is the case with the development of all types of media technology, the radio was initially a wartime innovation that was invented during the First World War to coordinate tanks, aircraft and submarines. It was not approved for civilian use until 1923, the Wehrmacht – Germany’s armed forces – having fiercely opposed any such move.In 1929, while still governor of New York, Franklin D. Roosevelt discovered that the radio could be used to communicate with his citizens in a way that was as powerful as it was intimate. Between 1933 and 1944, at that time as president of the United States, he systematized and perfected this format in 30 so-called Fireside Chats that allowed his warm and sympathetic voice to come across yet helped conceal the symptoms of his polio. The technology had removed the separation between public and private space.

Radio during the National Socialist era

At the same time, the Nazis in Germany had other – though at least equally effective – ideas for the radio. In August 1933, just a year after Brecht had published his speech about the function of radio in July 1932, the Volksempfänger was unveiled, a “people’s receiver” whose development had been commissioned by Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda Joseph Goebbels. From this point on, the “people” were to receive, and nothing more. Anyone who receives radio, and ideally with just a single channel, is receptive to orders from above – this was what the Nazis were counting on. “The National Socialists […] knew that broadcasting gave their cause stature as the printing press did to the Reformation.” [12] The number of radio receivers in the Third Reich grew from year to year.Bertolt Brecht’s voice and the voices of his numerous fellow political campaigners could no longer be heard, however. Brecht was unable to get people to embrace his visions of the participatory use of radio technology. In the year that the Volksempfänger was introduced, he escaped with his bare life from Germany.

Gonna keep my radio on

Till I know just what went wrong

The answer’s out there somewhere on the dial [13]

Footnotes

[1] Bertolt Brecht: "On Utilizations". in: Brecht: Writings on Literature and Art I 1920–1932. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1967, 127.

[2] Brecht: "The Radio as an Apparatus of Communication". in: Brecht: Writings, 138 f.

[3] Brecht: "Suggestions for the Director of Radio Broadcasting". in: Brecht Writings, 124.

[4] Brecht: The Radio as an Apparatus of Communication, 134 f.

[5] Brecht: "Radio – An Antediluvian Invention?" in: Brecht: Writings, 122.

[6] Brecht: "The Radio as an Apparatus of Communication", 135.

[7] ibid., 133.

[8] Brecht: "Radio – An Antediluvian Invention?", 121.

[9] Brecht: "The Radio as an Apparatus of Communication", 132.

[10] ibid.

[11] ibid.

[12] Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno: Dialectic of Enlightenment. Philosophical Fragments. Frankfurt am Main 2008 (first published: 1969), 168.

[13] Ray Davies: Around the Dial, 198