What is cultural heritage?

The Würzburg Residence and the Acropolis in Athens are considered cultural heritage, and have been recognized as such by UNESCO – a fairly undisputed decision. In England, however, scholars are currently debating whether Punk can also be considered a cultural heritage. A good occasion to get to the bottom of the question: What is cultural heritage?

By Nadine Berghausen

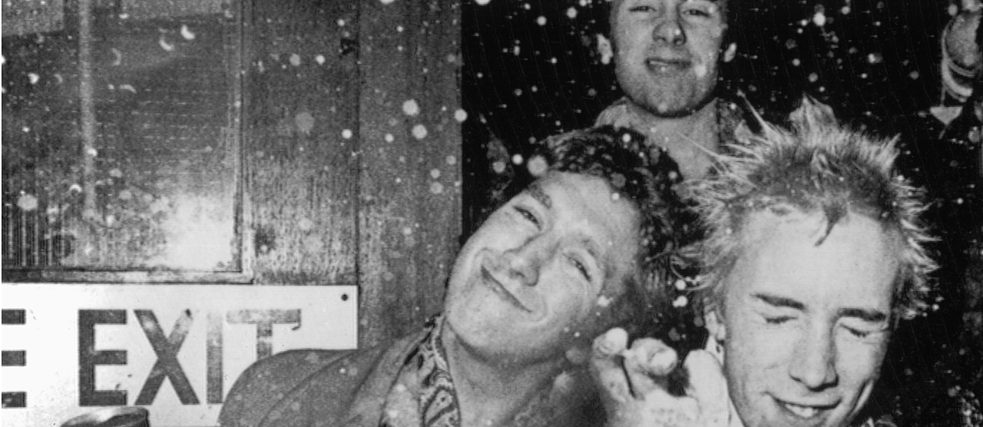

It will probably come as no surprise that the oldest surviving structures of the ancient world, like the Acropolis in Athens or the Pyramids of Giza in Egypt, are UNESCO world cultural heritage sites. But a completely different kind of cultural asset from the subculture par excellence, the provocative punk movement of the 1970s, is more likely to give some readers pause. Punk as cultural heritage, surly they’re having us on?

Yet British archaeologists are currently debating this very question: is the snotty, sometimes offensive graffiti Sex Pistols’ singer John Lydon doodled on the walls of number 6 Denmark Street in London in punk’s heyday cultural heritage or anti-cultural heritage, and is it worthy of protection?

UNESCO has recognized the Belgian tradition of shrimp fishing with draft horses, here in the Channel in Flanders, as intangible cultural heritage of humanity | Photo (detail): A. Hartl © picture alliance / blickwinkel

UNESCO has recognized the Belgian tradition of shrimp fishing with draft horses, here in the Channel in Flanders, as intangible cultural heritage of humanity | Photo (detail): A. Hartl © picture alliance / blickwinkel

The “World Cultural Heritage” title

According to UNESCO, testimony of past civilizations, artistic masterpieces and unique natural landscapes all meet the cultural heritage criteria if, “their destruction would represent an irreplaceable loss for all of humanity. Safeguarding them is not the sole responsibility of a single state; it is the responsibility of the international community.” Ten criteria were set out in the World Heritage Convention– among them artistic uniqueness, historical significance, and superlative natural phenomenon – and a potential candidate must fulfil at least one to be listed.The countries that have signed the World Heritage Convention can apply to UNESCO to have cultural assets recognized as World Heritage sites. By requesting this status, the state agrees to preserve the site or work of art for future generations. UNESCO’s objective is to globalize the conservation of culture and nature, and safeguard cultural diversity. Particular attention is paid to world heritage threatened by natural disasters, wars or decay. As such, UNESCO also employs cultural heritage status as cultural policy instrument.

While a national delegation submits the actual application, individuals, communities and organizations frequently initiate and support a bid for listed status. Applications undergo a standardized review process in which an international committee decides whether to award a “UNESCO World Cultural Heritage” title. UNESCO tries to maintain geographical and thematic balance as part of the process. Inclusion in the list of cultural heritage sites is a desirable honour that promises fame and an increase in tourism that advertising “World Cultural Heritage” status can bring.

A World Cultural Heritage list mainstay: the Acropolis in Athens numbers among the most famous structures built by the ancient Greeks | Photo (detail): Kay Nietfeld © picture-alliance / dpa / dpaweb

A World Cultural Heritage list mainstay: the Acropolis in Athens numbers among the most famous structures built by the ancient Greeks | Photo (detail): Kay Nietfeld © picture-alliance / dpa / dpaweb

What doesn’t make the cut?

Things can get quite interesting when UNESCO rejects an application. The country and citizen’s initiatives behind the bid often respond with incredulity and outrage, and demand to know why their important site not good enough to be included on UNESCO’s long list.Before making the grade in 2016, the work of Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier had to weather a few rejections and answer questions about the oeuvre’s universal significance. The serial nature of the proposal also proved problematic. The application addressed a coherent series of buildings and the experts on the UNESCO Committee feared that this might water down the tangible concept of a monument. But the Fondation Le Corbusier, which initiated the application, determinedly pursued an “all or nothing” strategy. The application-rejection cycle continued for a while, but doggedness won out in the end. The application by a select group of European spas towns labelled the “Great Spas of Europe” is a particularly complicated case. All these towns triggered a veritable boom in spa tourism in the 19th and 20th centuries, and include Baden-Baden, Bad Ems and Bad Kissingen (Germany), Baden (Austria), Montecatini Terme (Italy), Vichy (France), Spa (Belgium), Bath (Great Britain), and Františkovy Lázně, Mariánské Lázně and Karlovy Vary (Czech Republic). Here protected status would not affect an individual building, city, or landscape, but a group of component parts located in different countries. Transnational and serial applications present challenges because UNESCO requires coordinated management plans for serial nominations, and the sheer number of locations and countries involve can lead to delays and complications. The parties involved have worked on the application for a number of years and plan to submit it in 2019.