Forgotten Voices

Seven Feminists You Should Know

We all know Judith Butler and Beyoncé. But most of us have never heard of many of the women who fought for equality throughout history. Seven women you should know.

Von Sonja Eismann

Cynisca (around 442 BC – unknown)

Representation of Cynisca from 1825.

| Photo (Detail): © Public Domain

Admittedly, we do not know if Cynisca (also spelled Kyniska) considered herself a feminist, women’s rights activist or proponent of gender equality. Probably not, since neither these terms nor concepts existed in ancient Greece – even though today some consider Cynisca’s contemporary Plato a proto-feminist for the thoughts on gender equality he expressed in Politeia. What we do know, however, is that the rich Spartan princess was a devotee of the art of chariot racing. So much so in fact, that she became the first woman to win at the Olympic Games (396 BC). Since women were prohibited from officially competing at the games, she hired male charioteers to race her team of four. Which garnered her the kontinos, the winner’s wreath woven from an olive branch, for the horses she trained, since back then the prize went to the animals’ owner. Four years later, she pulled the same trick with the same victorious results, and was again not allowed in the stadium. The enslaved helots were forced to do all the daily labour for the Spartan elite like Cynisca, so others paid the price for the privilege she, unlike all other Greek women, had to participate in sports. She was not lacking in self-confidence either and commissioned bronze statues of herself and her chariot for the Temple of Zeus in Olympia. The inscription proclaimed her the only woman in all of Hellas to win the olive wreath. Cynisca’s victory had a large influence on her countrywomen, and quite a few, such as the victorious Euryleonis, Zeuxo, Timareta, Cassia and Belistiche, followed her example and started racing chariots. Women would not be officially admitted to the modern Olympics until the year 1900 though, and even then, they could only compete in a few disciplines.

Representation of Cynisca from 1825.

| Photo (Detail): © Public Domain

Admittedly, we do not know if Cynisca (also spelled Kyniska) considered herself a feminist, women’s rights activist or proponent of gender equality. Probably not, since neither these terms nor concepts existed in ancient Greece – even though today some consider Cynisca’s contemporary Plato a proto-feminist for the thoughts on gender equality he expressed in Politeia. What we do know, however, is that the rich Spartan princess was a devotee of the art of chariot racing. So much so in fact, that she became the first woman to win at the Olympic Games (396 BC). Since women were prohibited from officially competing at the games, she hired male charioteers to race her team of four. Which garnered her the kontinos, the winner’s wreath woven from an olive branch, for the horses she trained, since back then the prize went to the animals’ owner. Four years later, she pulled the same trick with the same victorious results, and was again not allowed in the stadium. The enslaved helots were forced to do all the daily labour for the Spartan elite like Cynisca, so others paid the price for the privilege she, unlike all other Greek women, had to participate in sports. She was not lacking in self-confidence either and commissioned bronze statues of herself and her chariot for the Temple of Zeus in Olympia. The inscription proclaimed her the only woman in all of Hellas to win the olive wreath. Cynisca’s victory had a large influence on her countrywomen, and quite a few, such as the victorious Euryleonis, Zeuxo, Timareta, Cassia and Belistiche, followed her example and started racing chariots. Women would not be officially admitted to the modern Olympics until the year 1900 though, and even then, they could only compete in a few disciplines.

Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648 – 1695)

Portrait of Juana Inés de la Cruz by Miguel Cabrera around 1750.

| Photo (Detail): © Public Domain

She taught herself Latin at the age of three, was doing maths by age five, and mastered the principles of Greek logic as a young woman – Juana Inés de la Cruz, born near Mexico City as the illegitimate daughter of a Spanish captain and a criolla (women of Spanish descent born in Latin America), was clearly a wunderkind. Early on, she realised how misogyny was holding women back when her attempts to attend the University of Mexico City dressed as a man were thwarted at the age of 16. She declined quite a few marriage proposals, choosing instead to live a nun so she would have enough time to devote to her studies, and could turn her cloister quarters into an intellectual salon. The scholar and poet fearlessly championed the rights of women to be intellectuals in the papers she wrote in the indigenous Nahuatl language, despite repeated orders from above to limit herself to strictly religious texts. Her criticism of the misogyny of the time ultimately resulted in condemnation from the Bishop of Puebla. She was forced to sell her collection of books and devote herself to charity for the poor, where she caught the plague and soon succumbed to it at the age of just 46. She languished in obscurity for centuries until Nobel Prize laureate Octavio Paz dedicated a book to her in 1989, leading to her rediscovery as one of the earliest proto-feminists.

Portrait of Juana Inés de la Cruz by Miguel Cabrera around 1750.

| Photo (Detail): © Public Domain

She taught herself Latin at the age of three, was doing maths by age five, and mastered the principles of Greek logic as a young woman – Juana Inés de la Cruz, born near Mexico City as the illegitimate daughter of a Spanish captain and a criolla (women of Spanish descent born in Latin America), was clearly a wunderkind. Early on, she realised how misogyny was holding women back when her attempts to attend the University of Mexico City dressed as a man were thwarted at the age of 16. She declined quite a few marriage proposals, choosing instead to live a nun so she would have enough time to devote to her studies, and could turn her cloister quarters into an intellectual salon. The scholar and poet fearlessly championed the rights of women to be intellectuals in the papers she wrote in the indigenous Nahuatl language, despite repeated orders from above to limit herself to strictly religious texts. Her criticism of the misogyny of the time ultimately resulted in condemnation from the Bishop of Puebla. She was forced to sell her collection of books and devote herself to charity for the poor, where she caught the plague and soon succumbed to it at the age of just 46. She languished in obscurity for centuries until Nobel Prize laureate Octavio Paz dedicated a book to her in 1989, leading to her rediscovery as one of the earliest proto-feminists.

Dolores Cacuango (1881 – 1971)

Wooden statue of Dolores Cacuango in Olmedo, Ecuador.

| Photo (detail): © Montserrat Boix/CC BY-SA 4.0

Everything seemed aligned against Dolores Cacuango’s rise to become one of Ecuador’s most important indigenous and feminist political activists. She grew up in bitterly poor conditions with her indigenous parents, who were forced slave away on a hacienda as basically unpaid indentured servants. Eight of her own nine children died in infancy due to poor hygiene. She never learned to read and write, but when Cacuango was forced to work as a maid for a wealthy family, she noticed the discrepancy between their children and those of indigenous parents: While the offspring of the rich went to school as a matter of course, education was not provided for her own community. She decided to found the first bilingual schools in which indigenous children were taught in both Kichwa and Spanish - and which were defamed as hotbeds of communism and closed by the junta in 1963. Dolores herself proudly identified as a communist and she was still imprisoned for her beliefs even at an advanced age. In 1930, she helped spearhead the three-month labour strike in Cayambé. Together with activist Tránsito Amaguaña, she founded the FEI in 1944, the first federation of indigenous Ecuadorians fighting for their rights. Today, the activist also known as Mama Dulu is revered as an icon by young indigenous people and feminists in her home country.

Wooden statue of Dolores Cacuango in Olmedo, Ecuador.

| Photo (detail): © Montserrat Boix/CC BY-SA 4.0

Everything seemed aligned against Dolores Cacuango’s rise to become one of Ecuador’s most important indigenous and feminist political activists. She grew up in bitterly poor conditions with her indigenous parents, who were forced slave away on a hacienda as basically unpaid indentured servants. Eight of her own nine children died in infancy due to poor hygiene. She never learned to read and write, but when Cacuango was forced to work as a maid for a wealthy family, she noticed the discrepancy between their children and those of indigenous parents: While the offspring of the rich went to school as a matter of course, education was not provided for her own community. She decided to found the first bilingual schools in which indigenous children were taught in both Kichwa and Spanish - and which were defamed as hotbeds of communism and closed by the junta in 1963. Dolores herself proudly identified as a communist and she was still imprisoned for her beliefs even at an advanced age. In 1930, she helped spearhead the three-month labour strike in Cayambé. Together with activist Tránsito Amaguaña, she founded the FEI in 1944, the first federation of indigenous Ecuadorians fighting for their rights. Today, the activist also known as Mama Dulu is revered as an icon by young indigenous people and feminists in her home country.

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (1880 – 1932)

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain

| Photo (detail): © Public Domain

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, better known as Begum Rokeya, was a pioneer of Bengali feminism. In 1909, she founded the first school for Islamic girls in Bhagalpur, which she moved to Calcutta two years later. The founding of Anjuman-e-Khawateen-e-Islam, the Islamic Women’s Association, followed in 1916. In addition to advocating for female education, sometimes going door to door to convince Muslim families to send their daughters to school, she wrote some of the earliest feminist science fiction stories. Ten years before Charlotte Perkins Gilman released her feminist utopia Herland in the United States, Rokeya, who also published essays on equality, wrote Sultana’s Dream. The book reverses the classic gender roles and women rule with the help of technologies such as flying vehicles, solar power, and weather control. The visionary story was not without humour either: daily working hours were limited to just two hours, since in the past men would have spent six hours smoking anyway. Bangladesh now celebrates Begum Rokaya Day on her birthday every year, December 9.

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain

| Photo (detail): © Public Domain

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, better known as Begum Rokeya, was a pioneer of Bengali feminism. In 1909, she founded the first school for Islamic girls in Bhagalpur, which she moved to Calcutta two years later. The founding of Anjuman-e-Khawateen-e-Islam, the Islamic Women’s Association, followed in 1916. In addition to advocating for female education, sometimes going door to door to convince Muslim families to send their daughters to school, she wrote some of the earliest feminist science fiction stories. Ten years before Charlotte Perkins Gilman released her feminist utopia Herland in the United States, Rokeya, who also published essays on equality, wrote Sultana’s Dream. The book reverses the classic gender roles and women rule with the help of technologies such as flying vehicles, solar power, and weather control. The visionary story was not without humour either: daily working hours were limited to just two hours, since in the past men would have spent six hours smoking anyway. Bangladesh now celebrates Begum Rokaya Day on her birthday every year, December 9.

Inji Aflatoun (1924 – 1989)

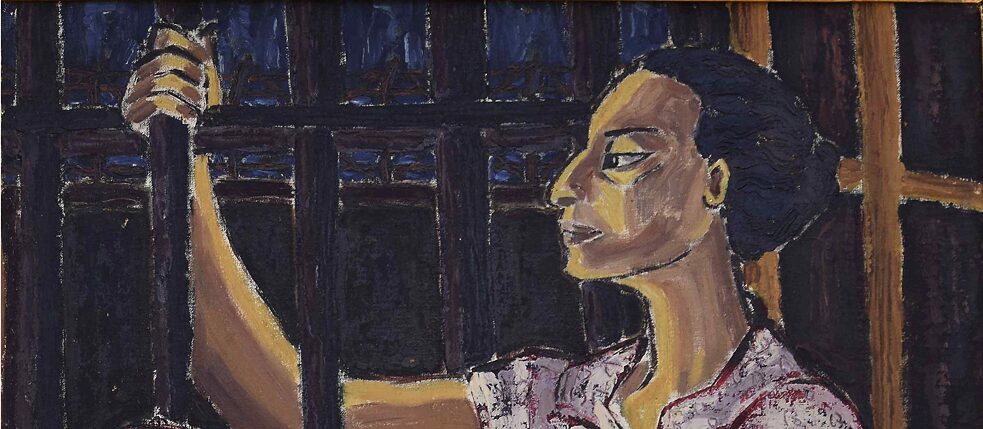

Inji Aflatoun

| Photo (detail): © Fair Use

What torments could a girl from a rich family possibly have gone through? This is what contemporary viewers of Inji Aflatoun’s early surrealist paintings are rumoured to have wondered. Born in Cairo in 1924 into a wealthy, traditionally Muslim family, the Egyptian painter and women’s rights activist was actually rebelling against her own class. She discovered Marxism at the Lycée Français in her hometown and later joined a communist youth organisation. By her mid-20s, she was already writing popular pamphlets such as Thamanun milyun imraa ma’ana (80 Million Women with Us) and Nahnu al-nisa al-misriyyat (We Egyptian Women), in which she linked her analysis of sexism to that of classism, placing both in the context of imperialist oppression. Under President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s persecution of communists, she was even imprisoned from 1959 to 1963. While she had painted mostly portraits in a style influenced by Cubism and Surrealism up to that point, she turned to landscape painting while in prison. This remained her subject matter even after her release – as a way, art historians posit, of using light and expansiveness to counteract the constrictions of imprisonment and the political situation. Today, her painting can be seen in museums and private collections worldwide.

Inji Aflatoun

| Photo (detail): © Fair Use

What torments could a girl from a rich family possibly have gone through? This is what contemporary viewers of Inji Aflatoun’s early surrealist paintings are rumoured to have wondered. Born in Cairo in 1924 into a wealthy, traditionally Muslim family, the Egyptian painter and women’s rights activist was actually rebelling against her own class. She discovered Marxism at the Lycée Français in her hometown and later joined a communist youth organisation. By her mid-20s, she was already writing popular pamphlets such as Thamanun milyun imraa ma’ana (80 Million Women with Us) and Nahnu al-nisa al-misriyyat (We Egyptian Women), in which she linked her analysis of sexism to that of classism, placing both in the context of imperialist oppression. Under President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s persecution of communists, she was even imprisoned from 1959 to 1963. While she had painted mostly portraits in a style influenced by Cubism and Surrealism up to that point, she turned to landscape painting while in prison. This remained her subject matter even after her release – as a way, art historians posit, of using light and expansiveness to counteract the constrictions of imprisonment and the political situation. Today, her painting can be seen in museums and private collections worldwide.

Ruth Bleier (1923 – 1988)

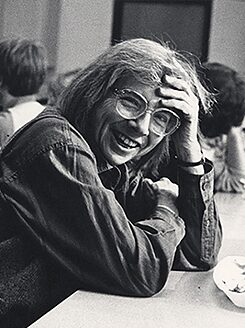

Ruth Bleier

| Photo (detail): © Public Domain / NIH National Library of Medicine

Is science always objective? U.S. neurophysiologist Ruth Bleier did not believe so – and in her work impressively proved how the foundations of biology were permeated by gender stereotypes. The daughter of Russian immigrants, she worked as a doctor in Baltimore’s poor inner city until her support of the Civil Rights Movement led to her being blacklisted as “un-American” by the government and banned from practicing. She then chose to further her education in the field of neurophysiology, and in her new position at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, she advocated for the establishment of a Women’s Studies programme, among other things. In the mid-1980s, she published two works on stereotypical gender assumptions in biology, Science and Gender: A Critique of Biology and Its Theories on Women (1984) and Feminist Approaches to Science (1986). Following the dissolution of her marriage, she came out as a lesbian and helped organise the lesbian-friendly restaurant Lysistrata in Madison as well as the A Room of One’s Own bookstore. Together with her partner Elizabeth Karlin, she fought for abortion rights before succumbing to cancer at the age of 64.

Ruth Bleier

| Photo (detail): © Public Domain / NIH National Library of Medicine

Is science always objective? U.S. neurophysiologist Ruth Bleier did not believe so – and in her work impressively proved how the foundations of biology were permeated by gender stereotypes. The daughter of Russian immigrants, she worked as a doctor in Baltimore’s poor inner city until her support of the Civil Rights Movement led to her being blacklisted as “un-American” by the government and banned from practicing. She then chose to further her education in the field of neurophysiology, and in her new position at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, she advocated for the establishment of a Women’s Studies programme, among other things. In the mid-1980s, she published two works on stereotypical gender assumptions in biology, Science and Gender: A Critique of Biology and Its Theories on Women (1984) and Feminist Approaches to Science (1986). Following the dissolution of her marriage, she came out as a lesbian and helped organise the lesbian-friendly restaurant Lysistrata in Madison as well as the A Room of One’s Own bookstore. Together with her partner Elizabeth Karlin, she fought for abortion rights before succumbing to cancer at the age of 64.

Maaliaaraq Vebæk (1917 – 2012)

Maaliaaraq Vebæk, 1982

| Photo (detail): © Hans-Erik Rasmussen / Fair Use

The first novel by a Greenlandic woman did not appear until 1981. The themes covered in Búsime nâpíneĸ (Katrine’s Story) explain why we had to wait so long. In her debut novel, Maaliaaraq Vebæk, daughter of the Greenlandic poet and catechist Josva Kleist who was primarily educated in Denmark, thematised the power relationship between Denmark and its colony through the fate of a woman. Louise, a young Greenlander, meets a Danish craftsman working in her homeland and follows him to Denmark. She soon discovers that she will never be recognized as an equal there because of her gender and her origins. She meets a compatriot, Katrine, who eventually takes her own life because of this exclusion. The sequel published in 1992 looks at the life of Katrine’s daughter and the racism she experiences. The planned third volume never materialised. Vebæk, who returned to Greenland after her education but later spent a lot of time in Denmark with her Danish husband where she also assisted him in his ethnological studies, acted as a translator and literary critic in addition to her busy literary life. In 1990 she published Navaranaaq og andre – a history of Greenlandic women.

Maaliaaraq Vebæk, 1982

| Photo (detail): © Hans-Erik Rasmussen / Fair Use

The first novel by a Greenlandic woman did not appear until 1981. The themes covered in Búsime nâpíneĸ (Katrine’s Story) explain why we had to wait so long. In her debut novel, Maaliaaraq Vebæk, daughter of the Greenlandic poet and catechist Josva Kleist who was primarily educated in Denmark, thematised the power relationship between Denmark and its colony through the fate of a woman. Louise, a young Greenlander, meets a Danish craftsman working in her homeland and follows him to Denmark. She soon discovers that she will never be recognized as an equal there because of her gender and her origins. She meets a compatriot, Katrine, who eventually takes her own life because of this exclusion. The sequel published in 1992 looks at the life of Katrine’s daughter and the racism she experiences. The planned third volume never materialised. Vebæk, who returned to Greenland after her education but later spent a lot of time in Denmark with her Danish husband where she also assisted him in his ethnological studies, acted as a translator and literary critic in addition to her busy literary life. In 1990 she published Navaranaaq og andre – a history of Greenlandic women.