Dance

Choreography as a form of protest

Politically motivated flash mobs and performances react to current questions of society with popular and contemporary forms of dance. For example, is it possible to give answers to oppression with the body? The theatre and dance scholar Susanne Foellmer explains how such a kind of protest can have a public impact.

Mrs Foellmer, you deal with the topic of “choreography as a medium of protest”. A well-known example of political protest is the action Standing Man in Istanbul - in Turkish Duran Adam - by the Turkish dancer and choreographer Erdem Gündüz. What is so special about it?

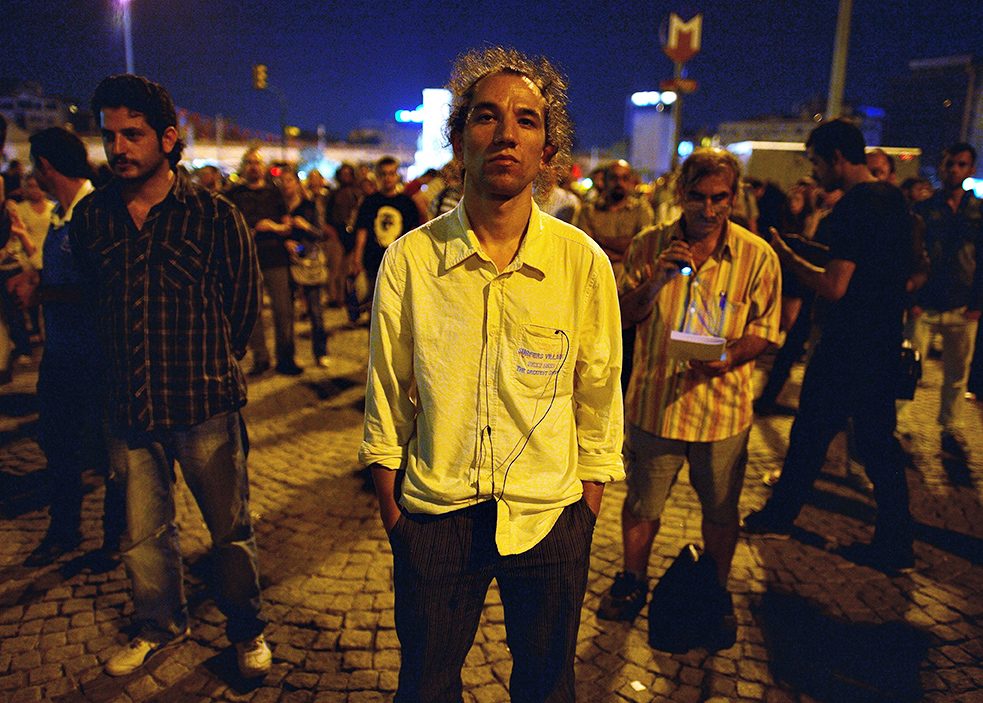

Erdem Gündüz’s Standing Man was originally a response to the ban on public assembly imposed after the 2013 protests in Gezi Park in Istanbul. Gündüz just stood there, looking at the Atatürk monument and not leaving. Others later followed his example and stood next to him. The action quickly went viral on social media. Maybe it wasn’t extreme in expression, but in any case it was a very much an action of resistance to which the police didn’t know how to respond. Because obviously it’s not forbidden to stand alone in a place. In this sense, it was a subtle action that subverted the ban on public assembly and demonstration. That it then suddenly began to spread at a media level, that it was shared multimedially, that there were repetitive effects, and that it became a political action wasn’t originally in the power of the "standing man".

Standing as a form of protest: the “Standing Man” in Gezi Park, dancer and choreographer Erdem Gündüz.

| Photo: © Vassil Donev/picture alliance/dpa

In most cases, protest is associated with a “louder” form of expression. Are standstill or slow movements even dance?

Standing as a form of protest: the “Standing Man” in Gezi Park, dancer and choreographer Erdem Gündüz.

| Photo: © Vassil Donev/picture alliance/dpa

In most cases, protest is associated with a “louder” form of expression. Are standstill or slow movements even dance?

The idea that standing can also be dance was formulated in the 1960s by Steve Paxton, one of the members of the Judson Church Theatre in New York. He called it “small dance”. Small dance because you don’t really stand completely still, because the body has to keep its balance. Some body part is always moving, even if imperceptibly. One example of this is the performance Constructing Resilience, which the Israeli choreographer Ehud Darash, who lives in Berlin, organized in the summer of 2011 in Tel Aviv. The occasion was protests against real estate price hikes. Darash, along with other dancers, took part in these protests; they counterpointed the forward movements of the demonstrations by standing in the crowd and slowly collapsing. A similar example already existed in the 1980s, at a time of social upheaval and protests, when the British choreographer Rosemary Lee performed what were called “melt down” performances in New York to protest against the ousting of artists from urban space. The performers met in public places, stretched their arms to the sky and slowly began to collapse, to melt, so to say. You can speak here of an artistic tactic that in fact becomes political.

In flash mobs, on the other hand, the dancing is often with lots of movement. What role do dance and choreography play here in the protest?

With a flash mob, to begin with, choreography is quite traditionally a pre-script. Users can watch a video on YouTube and learn the dance. For example, participants preparing to attend the annual Valentine's Day flash mob, “One Billion Rising”, where women around the world protest against violence. After watching the video, the protest is then carried into the street with your own body, a body that exposes itself to the existing social problems. It was similar with the protest in Gezi Park. Interesting is when the choreography makes its way back onto the Net after the flash mob and the dance spreads there. The question for me is: How is movement used to protest, and how is choreography - literally “writing down movement” - used to rewrite public space for a moment? It’s exciting to see how, for example, the forces of order re-choreograph by limiting the protests, by trying to wipe them out or by prohibiting online movement by censoring websites. Choreography has to do with how power is exercised, but also how power can be suspended or undermined for a moment.

Do you believe in the idea of the so-called “Facebook revolution", according to which the uprisings of the Arab Spring were possible only through the massive mobilization in social media?

I think you have to take a closer look here. In principle, it can’t be argued that a protest is effective only because of new information channels. There were also effective protests in the days of analogue media. Communication options such as Facebook or Twitter are particularly influential where access to public media is heavily controlled. But now even the social media are often under state control in autocratic regimes. Often they even allow activists to be tracked down. Here social media also have a downside. The question is always how power relations in these media are shaped.

Photo (detail): © Studio Menarc

Photo (detail): © Studio Menarc

susanne foellmer

Susanne Foellmer is a researcher in Dance Studies at the Coventry University Centre for Dance Research (C-DaRE) in the United Kingdom. She has collaborated with colleagues from the faculties of Communication Science and Sociology of the Free University of Berlin in an interdisciplinary research project on media practices in social movements, and is now conducting research in England on choreography as a medium of protest.