500th Anniversary of the Reformation

“Guided by the People’s Tongue”

“There is a time for everything.” Figures of speech used by 500 years ago have been passed down to our daily usage. The exhibition "Aufs Maul geschaut. Mit Luther in die Welt der Wörter" (roughly: "Guided by the People’s Tongue: With Luther in the World of Words") invites us to feel, hear, read and experience these words. We spoke with the curator, Friedrich Block.

What is the subject matter of the travelling exhibition “Aufs Maul geschaut"?

Friedrich Block: Martin Luther’s influences on the development of the German language and on today’s German are the focus of the interactive exhibition. Luther used phrases like “There is a time for everything,” “In your hand,” and “Our daily bread,” in his writings, especially in his translations of the Bible, and thus made them literary and preserved them for centuries. We still use them today. Eight installations illuminate linguistic history as well as aesthetic qualities such as the script and the sound.

How did Luther influence the German we use daily?

Far beyond the expressions I just mentioned, Luther harmonised written German: Lower and Upper German were united. He made significant contributions to the German that we speak today. We all know expressions that he himself partly invented; words and phrases that we use without knowing where they come from. “Dem Volk aufs Maul schauen” (literally, “Looking at the mouth of the people”), for example, is a common saying that originated in his Open Letter on Translating. He wrote, of the common people, “We must be guided by their tongue,” to learn about current language usage. Such phrases become condensed and thus develop the power to last for centuries.

How can language be exhibited?

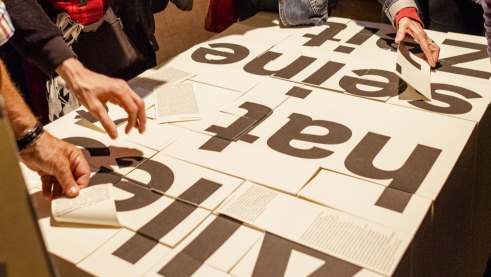

Exhibiting language means conceiving it for the exhibition space: in four dimensions and using multimedia. Language isn’t two-dimensional, but visual, tonal and it takes place in time. For example, to make it possible to spatially experience the phrase “There is a time for everything,” we dealt with the meaning of the word “time” (German: Zeit).

Originally, in Indo-Germanic, the word Zeit was associated with a process of tearing and breaking up. As a result, we have an installation in the form of a huge pad of paper, divided into fragments that can be torn off, each of which bears literary and documentary aspects of time. The meaning is symbolized in interactions with the visitors, in the process of tearing off the sheets of paper.

Can you give me another example?

“Man is born to work as the bird is to fly” is a quote from “The Sermon on the Estate of Marriage,” which is worded like an adage. During the Reformation, the word “Arbeit” (work) was positively revaluated. Work was no longer seen as burdensome and tormenting, but as a service pleasing to God. In order to show that “work” is always given different meanings, we selected a long list of compound words using Arbeit (work). Every few seconds, the display changes from “Fronarbeit” to “Arbeitsüberlastung.” This also highlights Luther’s creativity with words, as he invented many compound words himself, like “Lückenbüßer,” “Feuereifer,” “Machtwort,” which are still used today. The eight installations are also explored tonally. Phonetic principles of the expressions are filtered and intoned by an eight-voice choir consisting of individual sound elements, wood or copper. Dissected and re-arranged in a sound event, rhythmic forms become audible to the audience.

What can we still learn from Luther’s linguistic genius today?

We showed the exhibition at the new World of Grimm in Kassel in the context of the Brothers Grimm. The fact that they began their great dictionary of the German language with Luther sources reveals the esteem they had for his linguistic power. What we can still learn from Luther today is his effective use of down-to-earth language that did not trivialise the meaning, the imagery and tonal richness of the words and, of course, his attempt not to make the language an elite or geographically limited medium, but an accessible medium.