Europe’s Kitchen

What Europe’s Fringes Have to Say to Its Centre

The Zagreb writer, dramaturge and theatre director Ivana Sajko put on a play in Marseille in mid-November for “Europe’s Kitchen”, a project by the Goethe-Institut for Germany’s EU Council Presidency in 2020. In preparation for her work, she wrote the following essay as a commentary on the situation of south-eastern European cultural professionals during the pandemic.

By Ivana Sajko

On the eve of the parliamentary elections in Croatia, I came to Zagreb from Berlin. Before leaving, I had sent letters to friends from former Yugoslavia inviting them to a virtual dinner that I was preparing for the artistic project “Europe’s Kitchen” in Marseille. As my virtual guests, I deliberately chose those who come from the countries on the European fringes, from the lower end of the economic hierarchy, people who speak languages that hardly anyone else speaks and who invoke experiences that hardly anyone understands. I will only mention a few here by their first names: Goran from Zagreb, Petra from Ljubljana, Siniša from Belgrade. In my letters, I asked them a few questions, including how they interpret the symptoms of the disease that is now present everywhere and what they think is going on with the organism of Europe since the pandemic is also bringing other acute circumstances to the surface.

Europe is always somewhere else

The first reply came from Zagreb. Goran wrote to me that he didn’t think about Europe at all, because for him, that is for us, it was always somewhere else, somewhere across the border. “If I were to translate my own idea of Europe into a metaphor,” he wrote, “Europe would be like a block of flats full of smart apartments for the wealthy. You can walk past them. You can also go inside for a moment. But that’s all. I would preferably write Europe in lower case: europe. If europe were to sit at the table with us, it’s a guest I would never turn to.”Then a reply came from Ljubljana. Petra emphasised that the start of the pandemic in Slovenia coincided with the takeover of government by a right-wing coalition. They used the health measures to silence dissidents. The Slovene people have been protesting every Friday since the end of April. During their demos they ride through the city on bicycles and scooters, they try to develop new forms of public gatherings in order to circumvent increasingly rigid bans. She wrote me that everything possible was done in her theatre to be able to continue working, they tore the chairs from the auditorium and reduced the audience to a tiny group.“ I wonder why that wasn’t done in airplanes, for example?”, she wrote. "Is what we offer people less important than a trip to the other end of the world?” After so much effort to accomplish relatively little, her interpretation of the symptoms of the illness was filled with worry that culture and art might easily disappear from our lives.

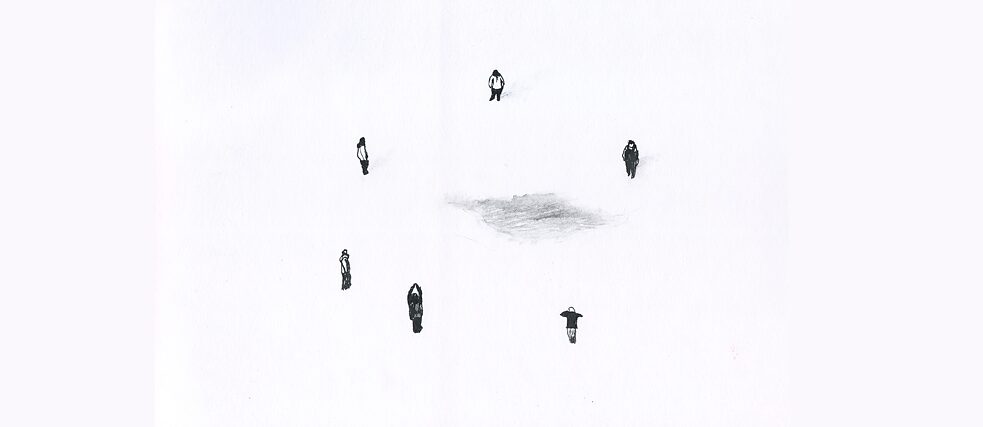

Siniša Ilić, “Social Distancing 5”, ink on paper | Illustration (detail): © Siniša Ilić 2020

Siniša Ilić, “Social Distancing 5”, ink on paper | Illustration (detail): © Siniša Ilić 2020

The pandemic directs the action

At the beginning of July, I went to a Zagreb theatre for the first time in a while to see a performance for which a group of authors, including myself, had written from the quarantine. The audience was divided into three small units that were scattered throughout the theatre so that they rarely met when possible. The first part was played between the clothes racks in the cloakroom, the second in the mirror opposite the ladies’ room, the third in the storage room for stage sets, the fourth in the sound booth, the fifth in the rehearsal room and the sixth on the roof. I stayed at the end of my audience group, feeling that I couldn’t get enough air under my mask. I felt stage fright as if I were on stage myself, which was true to a certain extent since the epidemiological measures actually helped to direct the action and since the success of the performance also depended on our collective improvisation. We as an audience were an authentic reflection of the crisis, but also an example of how it can be overcome.In the days when clouds of tear gas were floating over Serbia, Siniša reported from Belgrade. Forced to spend a full four weeks in self-isolation, he worked on a series of drawings on contemporary Europe. His specific imagery offers a picture of the world determined by the economy, in which gaps and spaces are particularly visible, while human bodies only exist as erased forms on which clothes, uniforms or masks hang. In the graphic cycle entitled “Social Distancing”, groups of people gather around an imagined centre. But this centre is just a smeared spot, alleged content with no message and no meaning, a void that points to something lost and that reminds us that the centre of our cohesion is empty.

A world of gaps and spaces

As in Siniša’s drawing, we have been caught looking at this situation for which we were not prepared. We lack the words to describe the state in which we find ourselves and we fail to see what we are looking at. In the state of emergency in which we are immersed, our survival can only be pure improvisation, like those that can be experienced in the middle of an auditorium or on the streets of Ljubljana circled by cyclists, or in front of the national parliament of Serbia where the students stop the police thugs with messages of peace like “You shall not beat these people,” or even in the results of the parliamentary elections in Croatia.In these elections, the leftist, green political platform called Možemo (“We Can”) managed to play a significant role as part of the opposition for the first time. They were able to win their votes for an election campaign without a budget by using social networks, through the help of many volunteers and thanks to their great reputation, which they enjoy due to their many years of work for the common good. The results of their campaign also depended on how much we, all of us who supported and trusted them for years, would manage to lure our neighbours out of political apathy and distrust of democratic processes.

For days, I sent messages and links to my mother, explaining the programme and plans of the Možemo platform and reminded her of the elections as soon as I got to Zagreb. She replied that she was disgusted by politics. But I persisted, and the next day I took her by the hand and almost dragged her to the polling station. Many of my colleagues did the same. That was an example of collective improvisation. Every vote counts. Every gesture is important. The success of our social performance depends on them. We learn that from the theatre. We learn that from each other. That is what europe’s fringes have to say to its centre.

This essay was first published in the taz on 14 November 2020.