Obituary

Helmut Kohl believed in Europe’s cultural dimension

The death of the former Chancellor Helmut Kohl is the loss of a friend and advocate of the Goethe-Institut. In many ways, the Kohl era also guided the work of the Goethe-Institut, particularly in the years following the fall of the wall.

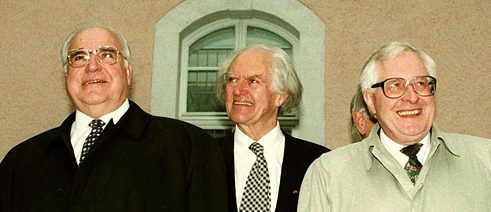

One of the most important shared milestones was the 1993 appointment of Hilmar Hoffmann as president of the Goethe-Institut. At that time, the Goethe-Institut operated 135 institutes in 75 countries. It may seem surprising that Kohl chose the former Frankfurt cultural affairs chief – an SPD figure. As Hoffmann recalled in an interview with the Frankfurter Neue Presse, party-political divisions played no part in their interaction, especially as he quickly impressed the chancellor with Hölderlin, recalling, “During a flight to South Africa, I recited a few verses.” The historian Kohl was astonished by the “well-educated social democrat.”

During Hoffmann’s almost ten-year term, twelve new Goethe-Instituts were opened, including in such politically significant places as Ramallah, Hanoi, Beijing, Dresden and Weimar. For the sixtieth anniversary of the Goethe-Institut, when asked about his happiest professional moment, Hoffmann referred to “a brief discussion mediated by Helmut Kohl with Nelson Mandela about the establishment of a Goethe-Institut in Johannesburg.”

Johannes Ebert, CEO of the Goethe-Institut, met Helmut Kohl for the first time in 1995 and says, “At the time, he welcomed the 750,000th student of the Goethe-Institut in Mannheim. In his notable speech, he spoke about dialogue, cultural collaboration, credibility and the necessity that even we Germans learn from one another. Many of these issues continue to be highly acute now – particularly in these turbulent European times, which also demonstrate to us how great the contribution made by the European Helmut Kohl was to a unified Europe.”

“He was a book lover”

In 1996, the chancellor opened the Goethe-Institut in Weimar. It was an historical moment in several respects. After all, it was the first institute in former East Germany and located at the formative site of the name-giver’s activities. “The initiative to devote more attention to the importance of classical literature and our cultural heritage for the present has taken on shape with the Weimar Goethe-Institut,” said Kohl in his speech. “We must learn from this example.” After all, Germany also has obligations to its partners all over the world. “Even to the people of France, Great Britain and Italy, a realistic image of Germany includes the presence of Beethoven and Brahms, Lessing and Heine, Schiller and Goethe.” In the spirit of the Goethe-Institut, Kohl conjured the “cultural dimension of European unification.”Klaus-Dieter Lehmann, the current president of the Goethe-Institut, also remembers a special moment with the chancellor during his tenure as a national librarian.

“In 1997, I had the privilege of inaugurating the new building of the Deutsche Bibliothek Frankfurt with Helmut Kohl. He was such a book lover that we almost put the entire ceremony at risk by excitedly rummaging through the bookshelves. While doing so, we developed a joint idea for a European Library, where the relevant literature would be translated into every European language and the library would be made available in every EU country. Helmut Kohl believed in the power of literature. That would also be an ideal programme for the Goethe-Institut and European publishers.”