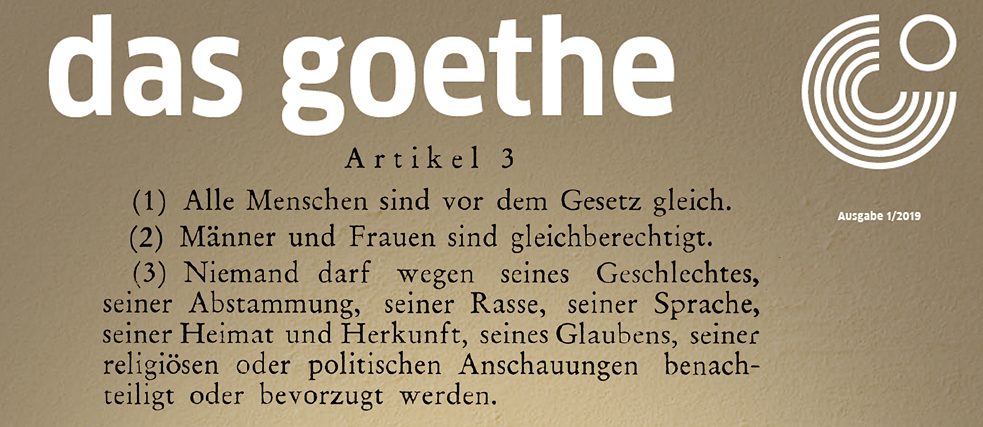

das goethe: Issue 1/2019

Blind Spots and Double Standards

On 13 June, the new issue of das goethe will be published with the theme “Cultures of Equality.” Read here in advance how the Egyptian anthropologist Dina Makram-Ebeid describes the feminism debates north and south of the Mediterranean – highlighting the responsibility of the “North” for poverty in the “South.”

By Dina Makram-Ebeid

In the summer of 2017, I spoke at the Goethe-Institut Cairo about feminisms in Europe and countries in the south of the Mediterranean. The workshop set the agenda for the Tashweesh cultural festival in late 2018. I admit I was a little concerned. On the one hand, the Goethe-Institut has been committed to social and cultural life in Egypt for many years. On the other hand, I wondered if a cultural institute would not take up the issue of equal rights in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) from a European perspective yet again.

As an academic, I had learnt how historically, the liberation of women and the fetishisation of gender relations had often been part of larger hegemonic and at times colonial projects that “pink-washed” more problematic socio-political practices by focusing on Arab or Muslim subjects, and particularly women, as the symbol of those in need of “saving.”

Feminism as a form of survival

To be able to engage in these debates, I needed to rethink and reconnect with what that feminism truly meant to me. As I pondered further, my ambivalence over the workshop invitation became clearer: feminism is both a form of survival and a disruption of the current order of things. The world is full of grave injustices, not just to women, but to people who are working class, to people of colour, to gender-nonconforming people and to all sorts of oppressed people, but also to land and ecologies and the spaces we share in common.Between killjoy and rule breaker

Instead, I would say that as a feminist, I strive to be somewhere between what academic and author Sara Ahmed would call a “feminist killjoy” – someone who makes everyone uncomfortable by asking the questions that are often silenced at the dinner table – and a “bad feminist” in the way the US author Roxane Gay puts it – as someone who isn’t doing her feminism “right” by strict standards. Gay thus criticises what she call “essential feminism” that tells us there are clear right and wrong feminisms without taking into account our own individuality, complexity, fragility and the nuanced contexts we operate within.I mean, what does it mean to discuss women’s rights and their access to public spaces without recognising how the ongoing climate disaster, which we in the South are paying the highest price for, makes our very access to the public space for most of the year a truly suffocating experience? How access to public spaces is never tied to it getting really hot in Egypt because countries in the global North are the biggest contributors to polluting this planet? Our access to public spaces is also shrinking because our streets have become open markets to international corporations competing to sell us everything they possibly can.

We need to keep queering our feminisms

Climate justice is one example that is full of potentials for new agendas and alliances. There is a lot more to build on in struggles feminists north and south of the Mediterranean are already engaged and making successes in; struggles about bodily integrity, sexuality and sexual violence and invisible and documented labour. The more we are able to locate our struggles in paradigms that consider global inequalities and sensitive intersectionalities, the more our feminisms might be grounded and relevant. Perhaps the task is to search for alternative languages and paradigms that open possibilities rather than foreclose them; that help us focus on the ambivalences, the missed conversations, the ambiguities and the bits we feel fragile about.The story of thinking of how to contribute to a workshop on feminist debates in a European cultural institute suggests that ambiguities, ambivalences, discomforts could be in fact generative. In a sense, there is a need to keep queering our feminisms. Not just by making them around LGBTQI rights, but also by queering our agendas, making them about the weird and the eerie, making them a sort of nuisance, a source of disruption and a destabilisation of the current order of things, mostly if we hope for feminism to continue to be, for many of us, a form of survival.

This is an abridged version of the essay. You can read the full version in das goethe.