Opening of the Exhibition The City of Tomorrow in Yerevan

The Communist Spirit in Everyday Life

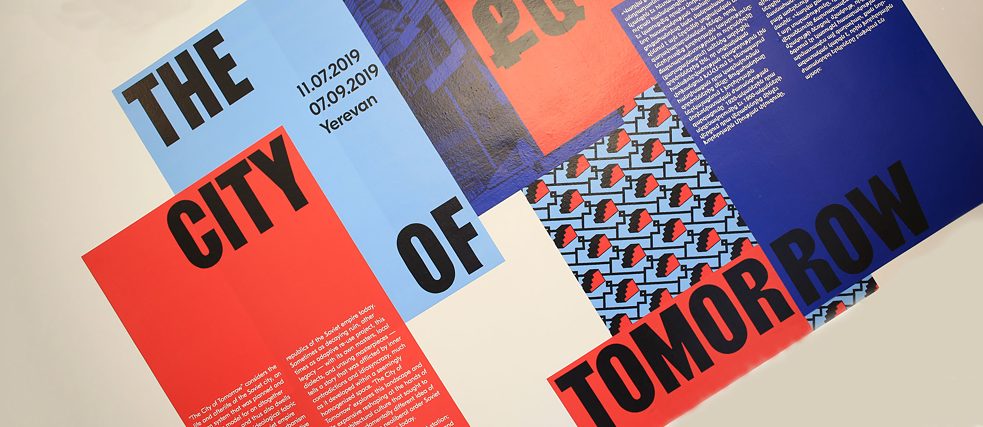

From Young Pioneer camps to artists’ houses to the Wedding Palace: The life and legacy of Soviet city planning and architecture continue to shape the urban landscape of the former USSR. Now the Goethe-Institut’s travelling exhibition The City of Tomorrow in the Eastern Europe/Central Asia region is devoted to Soviet Modernism.

By Natia Mikeladse-Bachsoliani

The Soviet city and its architecture were designed as a model for a new society. They were meant to convey a sense of social unity throughout the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The travelling exhibition The City of Tomorrow explores the architectural use of alternative societal ideas that feature emancipatory as well as oppressive and colonialist elements. Its focus is on the development of modernist Soviet architecture and its legacy today – with all its representatives, local dialects, and unknown masterpieces.

Visitors in Yerevan

| Photo: Ed Tadevossian

Visitors in Yerevan

| Photo: Ed Tadevossian

The Growth of Soviet Modernism

The ideological call for the modernisation of the USSR in the 1920s led to a radically new, modernist design vocabulary in urban planning and architecture. Soviet architecture was closely linked to the universal project of Modernism, especially the Bauhaus and Ernst May, who even made a development plan for Leninakan (now Gyumri, Armenia) on a journey through the USSR in the 1930s.After the end of the Stalin era, Soviet Modernism experienced a second heyday starting in 1955. Driven by the ideology of scientific and technological progress, architects now experimented with international concepts and adopted approaches from their suppressed legacy of the 1920s.

In search of an identity

In the 1960s, however, increasing criticism was heard about the industrialisation of space and architecture. Local elites and architects sought for a regional or national identity. Avant-gardes emerged that defied the equalising policy of the central Moscow bureaucracy.In the 1970s, another paradigm shift took place. Under Brezhnev, society adopted a more western lifestyle. The communist spirit in everyday life weakened. Architects reacted to this with new buildings: from the Young Pioneer camps to artists’ houses to the Wedding Palace.

Impressions from the past

| Photo: Ed Tadevossian

Impressions from the past

| Photo: Ed Tadevossian

The end or a revival?

With the collapse of the USSR in the early 1990s, Soviet Modernism came to an abrupt end. The majority of the utopian projects remained mere fragments or eventually failed. Many of the structures and forms have disappeared. Yet the concepts and buildings continue to leave their mark on many of the cities of the former USSR and a generation of young activists are now beginning to advocate for preservation and reinterpretation.The travelling exhibition itself is unorthodox and site-specific. In each city and each venue, it works with local archival materials, retaining only a sort of core that evolves differently in each new context.