New Edition of “das goethe”

Digital Colonialism

The new edition of “das goethe” with the theme “Digital Civil Society” will be issued on 16 January. On The Latest at Goethe, journalist Ina Holev explains how colonisation continues in the digital space.

By Ina Holev

Everyone is equal on the Internet; at least that’s what many people optimistically thought at the beginning of the millennium. When it gradually found its way in the late 1950s from military think tanks into academia and then initially a small public sphere, the Internet was considered a utopia. Hidden behind the mask of anonymity, all users would be equal and therefore would all have equal rights. There would be no hierarchies – not even among users in different countries.

Yet this hope that the Internet would be a non-discriminatory space remains an illusion to this day. Quite to the contrary, power structures are already firmly established in its technical infrastructure. They continue the history of colonialism in the virtual sphere in the form of “digital” or “electronic colonialism.”

Racist technologies

For example, many artificial intelligence algorithms are racist. Many face recognition programs used for surveillance are unable to recognise people of colour. Black women in particular are often incorrectly categorised by these technologies. This is mainly due to the programmers of these applications: Most of them are Western white men. It is much more difficult for them to differentiate people of colour than white people. This more or less subconsciously shapes their worldview and thus the technologies they develop.So things remain as they always were. Even when it comes to global networking, there is a global division into “North” and “South.” The colonial structures that emerged from the sixteenth century can be found in a new form today. The high-tech industry relies on the raw materials of the south. The rare earths now travel north along the old routes of slave ships. They are extracted in the countries of the south under sometimes horrendous conditions – cobalt in central African mines, for example.

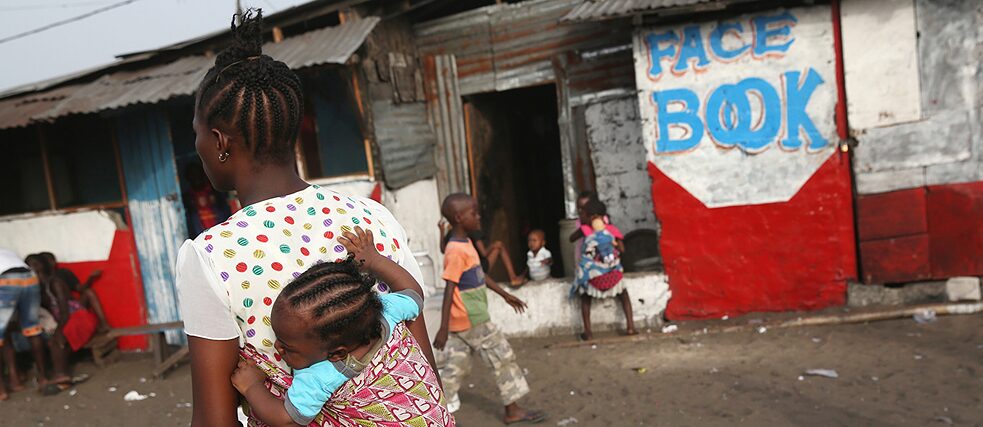

In Liberia, people pay to use the Facebook service Free Basics with their data.

| Photo (detail): © John Moore/ Getty Images

In Liberia, people pay to use the Facebook service Free Basics with their data.

| Photo (detail): © John Moore/ Getty Images

The cartels of the Internet giants

But digital colonialism goes much further. It penetrates the web almost completely and is “a new, quasi-imperial power structure imposed by dominant powers on a large number of people without their consent.” This is how human rights lawyer Renata Avila defines this continuation of colonialism.Avila is an activist from Guatemala and is one of the best-known critics of digital colonialism. In the Internet Health Report of the Mozilla Foundation, officially listed as a non-profit, she particularly criticises the close links between politics and technology. In autumn 2019, for example, in response to the unrest in Venezuela, the US government instructed the American company Adobe to block cloud services in the South American country. Avila therefore advocates stronger cartel regulation and a technology that serves the common good. She calls for alternatives to the corporations dominating the global Internet: Amazon, Facebook, Google and others. Local initiatives need to be strengthened. Her demand: “Decolonise the Internet!”

Payment method: personal data

However, local alternatives often fail because there is no access to the Internet in many regions of the world or the connections are far too slow. It’s a dilemma because the offers of the global players are, of course, also used in many regions of the Global South. And there, too, the Internet giants are happy to provide their services – but not for free. Since money is usually scarce here, the customers of these services pay primarily with their personal data.In 2014, Facebook started its Free Basics Internet service in some countries in Africa and South Asia. It’s an app that provides a slimmed-down version of the web. It is especially designed for regions with poor infrastructure and shows selected pages free of charge, many others cannot be accessed at all. The prerequisite for using Free Basics is logging in via a Facebook account – in other words releasing personal data.

India banned this service in 2016 and, along with other countries, is one of the major critics of these forms of digital colonialism. As a rule, these are states that have a colonial history and that today have comparatively well developed infrastructures. They are able to fortify their own national services and thus also the local economies.

The utopia of fairness

More and more stimuli are coming from the visual arts – especially media art – in the examination of digital colonialism. As “cyber feminists,” many artists criticise the colonial power structures on the Internet, but by using exactly the same digital means.The human rights lawyer Renata Avila from Guatemala wants the critics of digital colonialism to join forces to redesign the Internet bit by bit in many places. She knows quite well that the hope that one day there will be a decolonised, fair and non-discriminatory Internet remains a utopia. The digital world is still no different from the analog world.

This is an abridged version of this article. You can read the complete version in “das goethe”.