July 2018

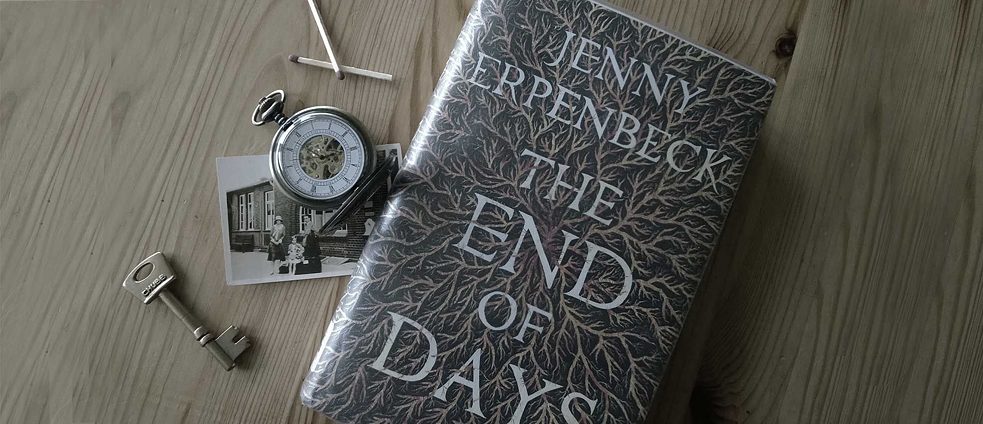

Jenny Erpenbeck’s The End of Days: A whole World of Reasons

Dominating literary shortlists and book club’s to-read lists, Kate Atkinson’s novel Life After Life was one of the standout books of 2013. Five years down the line, this wry, heart-wrenching, clear-sighted book continues to startle readers with its tale of a life lived many times.

The novel imagines the many possible lives (and deaths) of Ursula Todd, born into a stereotypically middle English family in 1910. Her lives are notably interwoven with the momentous events of the twentieth century: several versions see her fall victim to the Spanish Influenza of 1918, while in others she survives, later becoming a rescue worker during the Blitz, or a surprising friend to the notorious Eva Braun.

Remarkably, just one year earlier, a book with a very similar concept appeared in Germany: Jenny Erpenbeck’s The End of Days, which was published in English, translated by Susan Bernofsky, in 2014. Like Atkinson’s book, The End of Days considers the possible lives of a (this time unnamed) woman living through the milestones of the twentieth century. A remarkable and exciting book, The End of Days offers a fascinating counterpoint for British readers to Life After Life. Both are books about fate and chance, complicity and defiance.

Atkinson’s novel hones in on WW2 as the years which changed everything. The End of Days, however, offers a much more international, further reaching vision of the century. Born in a small town in Galicia in the early 1900s, Erpenbeck’s protagonist (in her various lives) grows up in Vienna, emigrates to Stalinist Moscow, and later becomes a successful writer in the German Democratic Republic. Poverty and prejudice are achingly present, at least in the first half of the book: food queues in post-WW1 Vienna last all night, and the spectre of the girl’s dead grandfather – killed long before her birth in a pogrom – shapes the course of her family’s lives.

Erpenbeck’s protagonist is no passive victim though. It is hard not to cheer when, about to “return home empty-handed after hours of waiting [at the WW1 food lines], she felt such fury that she called on the other women to march on the Rathaus with her to complain, she’d waved her handkerchief in the air above her head like a flag, and sure enough, hundreds of desperate women fell into step behind her – a girl of only fourteen.” As the girl grows up, Erpenbeck also captures the excitement of Communism following these hard years, the thrill of the promise of a new, better world.

While Kate Atkinson grants Ursula a vague awareness of her other possible lives, which allows her to learn from and avoid mistakes made in other lives, Erpenbeck instead focuses beautifully on the vagaries of chance, recognising the many minute details which can change the course of a life: the choice to turn right instead of left at a junction, or the chance encounter with an old friend at a café. After the death of the protagonist as a young woman, she reminds us that:

“There was an entire world of reasons why her life had now reached its end, just as there was an entire world of reasons why she could and should remain alive.”

Susan Bernofksy has translated a number of Erpenbeck’s novels, and she really captures the alternating distance and intimacy with which the author regards her characters, and the musicality evoked by repetition. The latter is strengthened through the interweaving of fragments of other texts. Most striking, perhaps, are the use of the Jewish scriptures in Book 1, in which the protagonist dies as a baby, and the confessions and suspicions of different Soviet citizens in the section set in Moscow.

I won’t lie: this is hardly a joyful read, and it lacks the redemptive humour which brightens Life After Life. Nonetheless, it is exquisitely written: a remarkable, necessary book.