Musa Okwonga: Excerpt

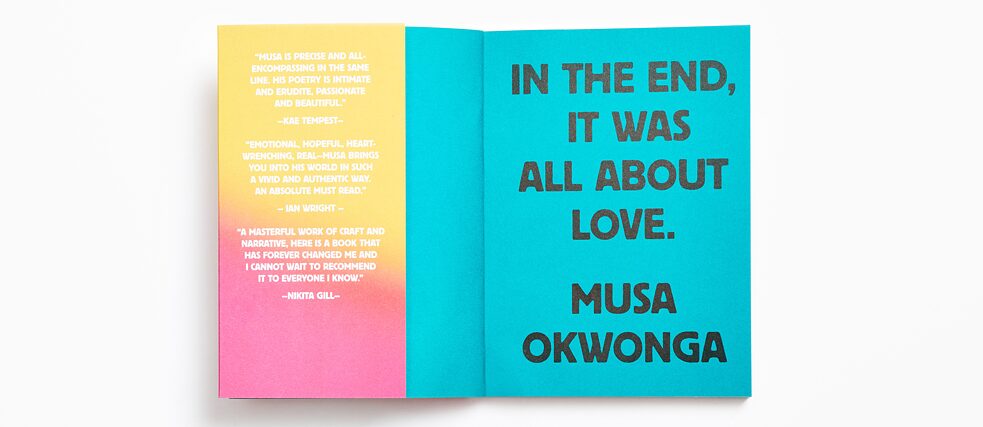

In The End, It Was All About Love.

What Brought You To Berlin?

Everyone asks you this. You answer glibly – that you came here to do four things: to write during the day, to see your friends during the evening, to fall in love, and to stay in love.

But that’s not the root of it. You came here to disappear. For the first few months you are in Berlin you are largely invisible, or at least as invisible as a dark-skinned black man in an overwhelmingly white city can be. The colours of your clothes mimic those of the city: concrete, tarmac, plaster. You wish to be as innocuous as a cobblestone.

You have had a suspiciously perfect start to life here. Perhaps Berlin can sense that it must go easy on you at first, that you are not yet battle- ready. Miraculously, you end up renting the very first flat that you view. It’s on the first floor on a quiet street in the near east of the city; all warm wooden floors and buttermilk walls, it’s your own small corner of honeycomb. Your landlady, a kind, softly-spoken knitwear designer, knows how hard it is for Africans to find places to rent here. She tells you the story of her three Moroccan friends with well-paying jobs who visited Berlin for a month, and who could barely get any apartment viewings in that time. I think, she says smiling, that my flat will be safe with you.

You feel safe here. It’s not far from the centre of town, but your nearest train station is one which few people outside your area have heard of. You’ve only been here a few months, and to your delight you are already beginning to vanish.

***

A Never-ending Blizzard Of Syllables.

There are many foods that have attracted your interest since you arrived in Germany, but the most intriguing of all these must be the schnitzel. You are fascinated by the schnitzel because it is not so much a meal as a thorough assault on the very concept of hunger itself. A thinnish slab of meat coated in breadcrumbs, it is a huge item, typically filling two-thirds of your plate. The largest one you have seen is not much smaller than a paving stone.

The schnitzel is Austrian but the Germans have adopted it with the vigour that the English have taken to curry. It is one of several immigrants to dinner tables in east Berlin, the more recent arrivals being Italian, Lebanese, Syrian, Colombian, Portuguese and Sudanese, but it stands apart from them in one crucial respect: it is generally consumed without the accompaniment of sauce. This is something you do not understand—this dish is biscuit-dry but many Germans eat it with no moisture other than a dash of lemon juice.

The startling dryness of schnitzel is in keeping with the Germans’ apparently robust attitude to discomfort. When you first have a hangover in the city, you go looking for painkillers on Sunday morning, only to find that every chemist in your area is shut till tomorrow. It feels like a punishment for getting hammered. The next time you have a hangover, you have long since invested in painkillers—but then you find that they are not as strong as the ones you bought in Britain, and still leave you with a substantial ache, as if to make you suffer a little further for your drunkenness.

German bureaucracy makes you work for it too. You have learned to treat each new avalanche of admin as different stages of an assault course, at the end of which you will achieve integration in German society. The language sometimes seems like a neverending blizzard of syllables, even to someone who studied it at school. But slowly, gently, you make your way, dealing with the Künstlersozialkasse, acquiring your Anmeldungsbestätigung. Each month, you pass a new test; each month, the place you fled fades from view.

***

You Wish Your Skin Were A Visa.

You wish your skin were a visa, since there are several places it cannot travel. It cannot go to certain European towns, because when it does it may be set upon by local youths, provoked by its confident passage down the middle of their streets. It cannot visit certain boardrooms, certain hearts. What a time to have a migrant body. What a time to live within this terrifying vehicle, this dark bulk.

What a time to be in this migrant body. When there are several of you in a particular train carriage in Hamburg, a cluster of dark-skinned men of African heritage, you begin to think: are there too many of us to make them comfortable? There are five of you, sitting in adjacent booths. Five! The other men are strangers but they have just boarded the same train and in their dress, Puffa jackets, oversized trousers and trainers, they are indistinguishable from you. Maybe if you dressed differently from these black men, the other people in the carriage would feel safer, that you were not part of a pack. Maybe you would feel safer, because you would not be seen as one of Them.

Look at the way you think about yourself now. African. Dark-skinned. Migrant. Fifteen years ago you were simply British, part of an apparently thriving whole. But now, with each passing year, your identity is being divided up, with each element progressively more dangerous.

Sometimes you forget you are in this migrant body and then the news reminds you. You are heading back to Berlin from Hamburg, tired but elated after a day of recording new music, when you see some troubling footage being shared on social media. A black man is lying on the street in one of Berlin’s busiest districts and the police, instead of simply arresting him for whatever offence they have perceived, are striking him. You send a text to a friend, asking if they will meet you for a drink when you get back to town, and when you see them that evening you plead if you can spend the night at theirs, because you do not want to be alone in your flat just now: alone with thoughts of just how hated you are, in this migrant body.

***

Berlin Is Not A Bubble.

Berlin is not a bubble. Many people will call it that, even those who should know better. It is not a bubble. A bubble is a carefully-sealed world whose occupants are oblivious to everything that happens beyond it. Berlin is something different. It is a refuge, an enclave, a safe haven. If Berlin were your bubble then that would mean you were incurious about whatever happened in other parts of the world. But you are acutely aware of those happenings, and that is why you are here. There is a very good chance that you are here because you fled the true bubbles of our societies—the small suburbs and villages where you were raised, where your difference was at best tolerated. There is a very good chance that those places, those bubbles, will resent how you see them now, that they will interpret your distance as elitism and snobbery as opposed to an essential act of self-protection. Those places, those bubbles, will not stop to think about what they did to you, that you were so traumatised that you had to flee at the earliest opportunity.

Berlin is not a bubble because that implies that there is some kind of protective force-field about this city, and there is not. Looking at history, looking at the Stolpersteine, those bronze plaques that mark the doorways Jews were abducted from, you can see that this city has not protected everyone.

Note: Excerpt from the book In The End It Was All About Love. With the kind permission of the publisher Rough Trade Books.

© Creation Company

Musa Okwonga (born 1979 in London) is a writer, broadcaster and musician. The co-host ofthe Stadio football podcast, he has published one collection of poetry and three books about football.

© Creation Company

Musa Okwonga (born 1979 in London) is a writer, broadcaster and musician. The co-host ofthe Stadio football podcast, he has published one collection of poetry and three books about football.

His work has appeared in various outlets, including Africa Is A Country, Byline Times, Foreign Policy, The Guardian, The New York Times, The Economist and The Ringer. He lives in Berlin.