Looted Cultural Assets

“We are running out of time”

Six German libraries set up a dedicated database that would allow them to combine research into looted cultural assets in their collections. Tracking down the previous owners requires some serious detective work.

The cultural assets looted by the Nazi regime between 1933 and 1945 included a large number of books. In a targeted campaign, the libraries of Jewish communities, freemasons, monasteries and political parties were plundered, both in Germany and abroad. Furthermore, the Nazis stole countless books from private individuals who fell victim to their persecution.

In many cases, German cultural institutions profited from this, with huge numbers of looted books ending up in the collections of public and academic libraries in particular. Some because they were allocated directly to them by the National Socialists, and others – including in the post-1945 period – because libraries purchased them as second-hand books. For the most part these acquisitions were poorly documented, which is what makes it so difficult to trace the origin of stolen books today. Provenance researchers are therefore hard at work in many libraries in Germany to identify looted works in their own collections so that the books can be returned to the original owners or their heirs.

Late discovery

“It was long the case that the question of cultural assets looted by the Nazis was paid hardly any attention at the Central and Regional Library Berlin (ZLB)”, explains provenance researcher Sebastian Finsterwalder. In 2002, however, a colleague discovered that the ZLB’s collections contained a number of easily identifiable books that had been seized by the Nazis when the Karl Marx House in Trier was expropriated in 1933. Further research revealed that Berlin’s Municipal Library had acquired more than 40,000 books from the Municipal Pawn Office Berlin in 1943. “It is clear from correspondence and acquisition lists that these were books taken from the flats of deported Berlin Jews”, continues Finsterwalder. The more thoroughly the researchers combed the shelves of the ZLB, the more obvious it became: “This library is full of looted books.”

7,000 names, 30,000 indications

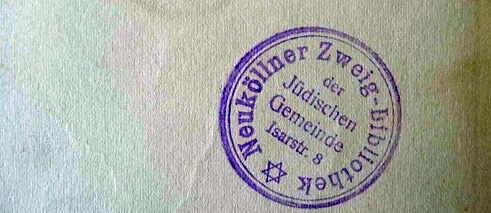

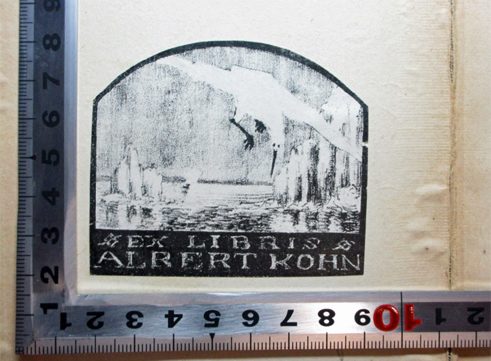

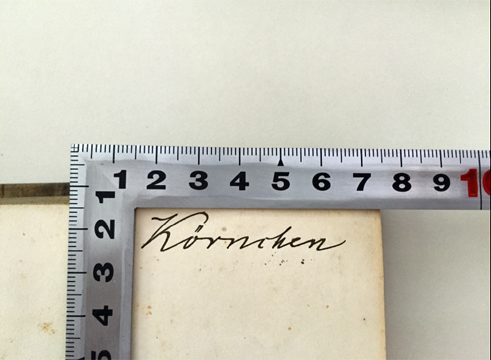

Tracing the origins and previous owners of stolen books is often a tedious and laborious business. Not infrequently the stamps or dedications that could have provided clues as to the former owners have been torn out. Consequently, a library’s provenance researchers have to work their way through an enormous number of investigative processes – using the Internet, archives from different countries, procurement lists compiled by the Nazis, newspaper advertisements and many other sources.

To relieve the burden on individual institutions and to combine and interlink the research and information, a dedicated Looted Cultural Assets database was established in March 2016. Cooperating on the project are the ZLB, the libraries of the Freie Universität (FU) Berlin and the University of Potsdam, the library of the New Synagogue Berlin – Centrum Judaicum Foundation, the Institute for the History of the German Jews (IGdJ) in Hamburg and, since January 2017, the Baden-Württemberg's State Library. Around 7,000 names of individuals and institutions, as well as roughly 30,000 indications of provenance, are recorded there in the beginning of 2017.

The database also records research findings that indicate that a particular book turned out not to be stolen – which in case of doubt can also save time. This distinguishes the database from the similar Lost Art archive of the German Lost Art Foundation in Magdeburg, which documents only information relating to Nazi-confiscated or looted artworks.

Purple ink as a clue

Following a relaunch next spring, the Looted Cultural Assets database will also make it easier for non-professional researchers to search for objects and names. Currently, the database primarily allows researchers to compare information and clues. Finsterwalder uses the biochemist Carl Neuberg to illustrate just how complex and time-consuming this work can be in some cases. Neuberg headed the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin until the Nazis banned him from pursuing his work and drove him to emigrate. Eight volumes from his collection were initially discovered in the Berlin Municipal Library – “scientific case studies whose titles alone were too specific for our collection”, as Finsterwalder explains.

However, the books also revealed things about the way Neuberg worked: “He noted page numbers on the spines of books and highlighted important passages by adding two lines in purple ink.” This eventually allowed books that he had owned to be identified even when for example the flyleaf containing his address stamp had been removed. “In total, we found another 33 volumes”, recounts the provenance researcher: “This is the biggest collection from a private library that we have been able to return to the owner’s heirs so far.”

Research as an obligation

Carl Neuberg’s heirs, who live in the USA, were not particularly interested in scientific papers in old German Gothic script. So they donated the works to the Leo Baeck Institut in New York, a centre which documents and researches the history and culture of German-speaking Jews.

The restitution of these looted works rarely makes the headlines or causes any dispute. Apart from fulfilling a legal and ethical obligation, the objective of provenance research is to “give the victims back their names and history” – as Ringo Narewksi, head of the administrative department for the restitution of Nazi-confiscated assets at the FU, put it in an interview.“ But we are running out of time”, warns Sebastian Finsterwalder. “With each new generation more of the memories die out.”

![Mark of provenance: (unbekannt), Stempel: Abbildung: allgemein, Abbildung: Emblem, Initiale; '[Sonne, Eule, Bücher, T]'.](/resources/files/jpg574/stempel-formatkey-jpg-default.jpg)

![Mark of provenance: - (Ascher, Hermann), Stempel: Name; 'Ex bibliotheca Hermann [i] Ascher Berolin. '.](/resources/files/jpg574/berolin-formatkey-jpg-default.jpg)

![Mark of provenance: - ([...], Hans ), Von Hand: Widmung: Allgemein, Name, Ortsangabe, Datum: Allgemein; 'Wenn auch weit von Dir entfernt, so denke ich doch stets an Dich Von Deinem Bruder Hans als er in Montreux war Montreux, den 12. Juli 1936 כ׳ב תמוז תרצ׳׳ו לפ׳׳ק'.](/resources/files/jpg574/montreux-formatkey-jpg-default.jpg)

![Mark of provenance: J / 297 (Naumann, Otto), Von Hand: Widmung: Allgemein; 'Herrn wirkl. Geh. Ober-Regierungsrath Dr. Nauman[n] Hochachtungsvoll [...]'.](/resources/files/jpg574/schrift-formatkey-jpg-default.jpg)