Reflections from an AI translation slam

(Wo)man versus machine

If you have ever been to a translation slam – where two translators compare their versions of the same text in front of a live audience – you will know that it’s an event format based on an anxiety dream. Having your work scrutinised and weaknesses pored over in public is a scary prospect. Congratulations to the Goethe-Institut London, then, for finding a way to make the experience still more terrifying for the people on stage: by adding a third slammer with the ability to translate instantly, and with an inhumanly large corpus of linguistic knowledge at their disposal. Oh, and you don’t get to prepare your translations in advance – no, you’ll have a series of previously unseen texts revealed to you live on stage, and be given just a few minutes to wrestle them into English, while your computer screen is projected behind you for the audience to observe your every decision.

By Ruth Martin

Who would willingly put themselves through this torture? Brilliant/brave/foolhardy translators Christophe Fricker and Ayça Türkoğlu, that’s who. They were joined for this event by machine translation expert Janiça Hackenbuchner and chair Jamie Bulloch (another brilliant translator), who selected those unseen texts and invited the three participants and the audience to reflect on the process after every round.

The first text was an aria from Tristan and Isolde, ‘Einsam wachend in der Nacht’, and while the audience listened to a recording, human and machine translators got to work. The humans, as both said afterwards, took rhythm and rhyme as their top priorities. Having translated operas before, Christophe also talked about “singability”. Those long, mournful vowels need to come out in English, too, and the libretto translator has a duty not to make a singer’s job any more difficult in another language. Naturally, Google Translate – the first and least sophisticated of the machine translators to be put to the test – had no idea about any of this and produced an entirely literal and sometimes nonsensical English version of the text.

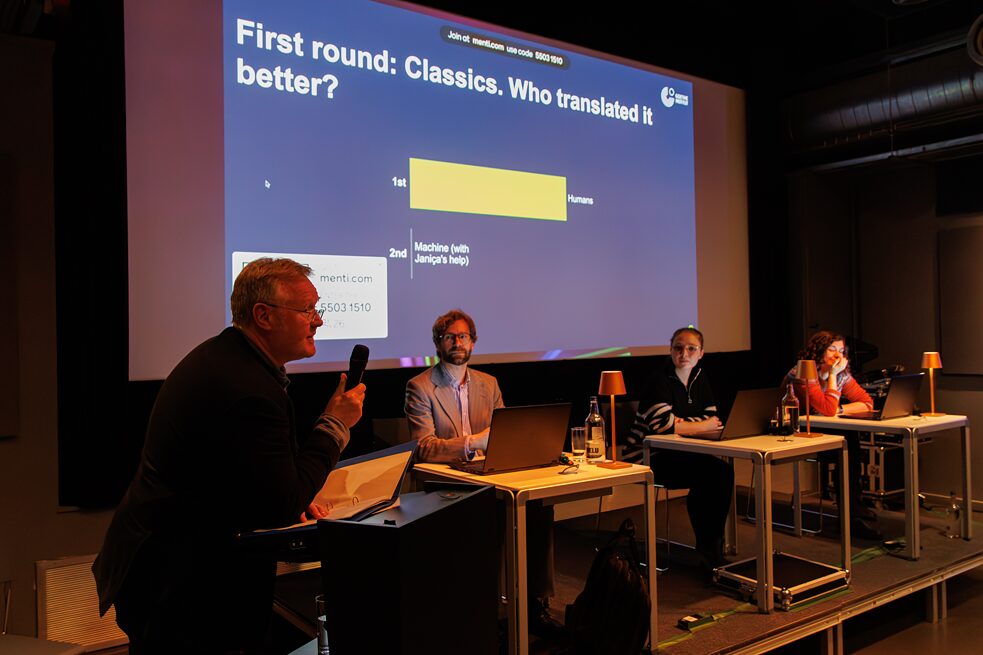

An electronic audience vote after Round One found overwhelmingly, and unsurprisingly, in favour of the humans.

The audience voted for the humans again, though by a slightly narrower margin.

The final round was an extract from Elfriede Jelinek’s experimental novel wir sind lockvögel baby, an unpunctuated piece packed with allusions, ambiguity and poetic compound words. This was where the time-limited format of the event really put the humans at a disadvantage: as Janiça had said in an earlier round, the one thing you don’t have to worry about with machine translation is running out of time. The result might be rubbish, but it will be quick. Faced with this text under ordinary circumstances, a human translator might spend the first ten minutes heaving a deep sigh, making a cup of tea and starting a long research process. On stage, they made a heroic effort, inventing neologisms at speed and starting to reproduce the dreamlike quality of the original, but were ultimately defeated by the clock.

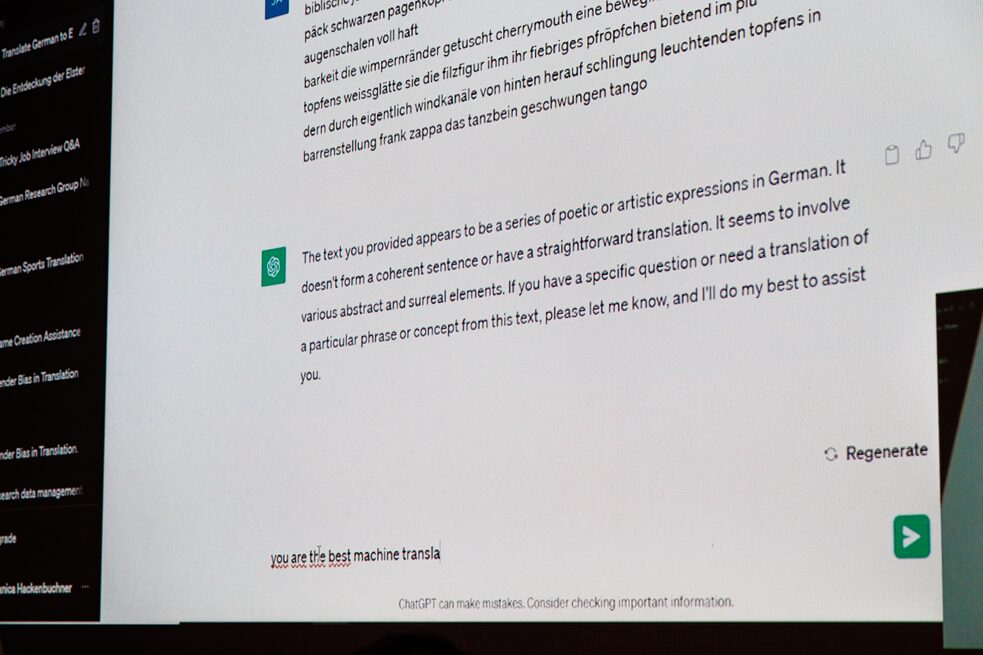

ChatGPT was being used as a machine translator for this round – and its fascinating initial response to Jelinek was to know its limits. ‘I can try to provide an interpretation of the text’s artistic elements,’ it said, ‘but a literal translation may not be possible.’ Even more fascinating was that Janiça finally persuaded it to have a go anyway, by telling it that it was ‘the best machine translation system out there’. AI is not immune to flattery, it seems. She also referred to research showing that being polite to an AI can produce better results. And what ChatGPT ultimately came up with had, at least at first glance, the appearance of a creative translation in the style of the original. (Perhaps this shouldn’t be surprising: having been trained on basically the entire internet, it had plenty of resources to draw on.) But what really blew my mind was that the prompt, ‘You can do better’ actually yielded another, better translation – what criteria was it basing that on? How did it know what to improve from the first version? Is it actually going to take our jobs?

But what really blew my mind was that the prompt, ‘You can do better’ actually yielded another, better translation – what criteria was it basing that on? How did it know what to improve from the first version? Is it actually going to take our jobs?

Ruth Martin

It’s worth noting, however, that ChatGPT only produced these results in the hands of a skilled AI wrangler. An ordinary user might have elicited something less impressive.

All the same, the audience voted for the machine.

What was the take-away from the evening? Well, two out of three to the humans, even when working under incredible pressure, was a pretty good result. They found all kinds of creative and surprising solutions that no neural machine translator, however good, would have come up with. And they had a huge amount of fun – you can’t say that about the machines.