An Overview of Contemporary German Plays

Bengali Translations and Productions

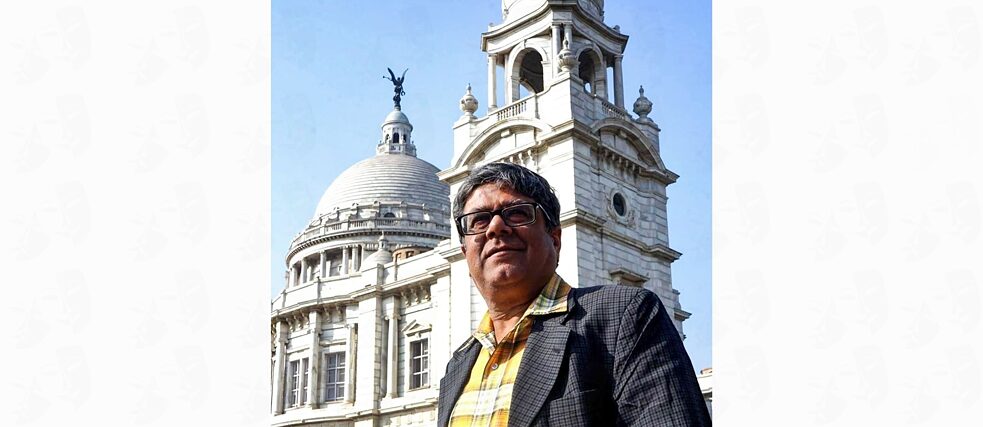

By S. V. Raman

Meaningful and thought-provoking theatre with socio-political relevance has been a deep-rooted tradition in different language groups of the Indian subcontinent since ages. In this context Bengali theatre has played a significant role in pre- and post-independent India. With the so called Group Theatre Movement gathering momentum in the metropolis of Calcutta and other districts of the state from the sixties of the last century, the search for socially relevant plays beyond the available indigenous materials moved to other parts of the world, mainly France and Germany. Thus Molière and Bertolt Brecht started making inroads into the hitherto monopoly of William Shakespeare as playwright(s) from abroad.

This piece essentially dwells on the pioneering role of the Goethe-Institut / Max Mueller Bhavan Calcutta in promoting and supporting the translation of contemporary German plays into Bengali and their subsequent staging by highly competent non-professional groups of the Group Theatre genre, based on first-hand knowledge and experience over nearly four decades. The first such endeavour that comes to mind was in the early 1970s as part of a weeklong festival of contemporary German plays staged by different groups, which included Die Physiker (The Physicists) by Friedrich Dürrenmatt, Biedermann und die Brandstifter (The Fireraisers) by Max Frisch, Der zerbrochene Krug (The Broken Jug) by Heinrich von Kleist and Der aufhaltsame Aufstieg des Arturo Ui (The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui) by Bertolt Brecht. Most of these plays were translated from the original German into Bengali by Nihar Bhattacharyya, at that time a teacher of the German language at the Goethe-Institut. Some of these Bengali translations even got published by local publishers. Most of the Bengali theatre directors at that time and even later were left-leaning in their ideology. This was reflected in the kind of plays that they opted to choose to stage in Bengali translation/adaptation.

One such director was Sekhar Chatterjee who had a long association with the Goethe-Institut. During a visit to the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic he had the occasion to witness a few theatre productions. Enthused by what he saw at the Berliner Ensemble, he designed his Bengali production of Arturo Ui (mentioned above) on similar lines and met with huge success. He also went on to stage Herr Puntila und sein Knecht Matti (Mr Puntila and his Man Matti) and Der Brotladen (The Breadshop). Puntila turned out to be a very popular production and the shows continued periodically for nearly three years. Some of the other inspirations that Sekhar Chatterjee brought back from Germany resulted in Bengali translations and productions of Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s Der Besuch der alten Dame (The Visit) and Peter Handke’s Publikumsbeschimpfung (Offending the Audience). During his stay in Germany, Chatterjee had the occasion to meet the playwright Franz Xaver Kroetz and witness the staging of a couple of his plays. He was so overwhelmed that immediately on his return he persuaded Nihar Bhattacharyya to translate Das Nest (The Nest) and Oberösterriech (Upper Austria) into Bengali. Chatterjee’s excellent non-proscenium productions of these two plays, the former in a library space and the latter in a small school compound, were runaway successes and were performed several times during the next couple of years. This also aroused a lot of curiosity and interest in other plays by Kroetz. Sensing this, the then director of the Goethe-Institut in the early 1980s, Hans-Jürgen Nagel invited Kroetz to visit Calcutta for a few weeks to witness the Bengali versions of five of his plays as well as take part in some discussions on theatre. Sekhar Chatterjee added Agnes Bernauer (Agnes Bernauer) to his above cited repertoire, while another young and promising director Anjan Dutt came up with very bold and daring productions of Stallerhof (Farmyard) and Heimarbeit (Homeworker).

Meanwhile, the obsession of Bengali theatre with Brecht continued, almost like a leitmotif. Apart from the fact that a Left Front comprising communist parties and allies took over the governance of the state of West Bengal in 1977 – incidentally, they remained in power for 34 long years, till they were overthrown in 2011 – Bengali theatre also had a strong tradition of using songs in theatre, a style adopted in several of Brecht’s plays. Being an established musician and musicologist himself, Hans-Jürgen Nagel motivated and even actively helped Anjan Dutt stage Bengali versions of Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera) and Happy End using the original scores by Kurt Weill. It was not unusual to find several Brecht plays being performed simultaneously on Calcutta stages – at one point there were three parallel productions of Der Augsburger Kreiderkreis (The Caucasian Chalk Circle) by different groups in the city.

A South Asia tour of Tankred Dorst organised by the Goethe-Institut in 1979 provided the opportunity to translate and stage some of his plays in different Indian languages. Thus Groβe Schmährede an der Stadtmauer (Big Diatribe at the City Wall) and Eiszeit (Ice-Age) got translated into and staged in Bengali. In the interim Peter Weiss also briefly caught the attention of a couple of theatre directors, resulting in two of his works being translated into and performed in Bengali – namely Mockinpott and Marat-Sade. It was during the rehearsals of the latter that the actor/director Anjan Dutt enamoured world renowned film director Mrinal Sen with his acting talent, which gave him his first break in Bengali cinema.

A rather difficult Bengali translation of Botho Strauβ’s play Trilogie des Wiedersehens (Trilogy of Reunion) was rendered in a stage version directed by Sohag Sen. Shortly thereafter, the much publicized visit and 6-month stay of Günter Grass in Calcutta in 1986-87 saw an array of events organised in the city in honour of the author, who thirteen years later was bestowed with the Nobel Prize. One such event, triggered by the author’s own wish during his stay, was the translation and staging of his play Die Plebejer proben den Aufstand (The Plebeians rehearse the Uprising) directed by Professor Amitava Roy. It created a few ripples that died down soon.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 brought the works of Heiner Müller to the notice of Bengali theatre directors. Anjan Dutt took up that challenge of staging three of his plays in Bengali translation. While Der Lohndrücker (Lowering the Wages) turned out to be somewhat of a damp squib, the double bill of Der Auftrag (The Mission) and Mauser on the same evening made audiences sit up and take notice of the inherent political power in these works.

In the year 1990 War and Peace was the overarching theme for a year-long series of events conceived of in various disciplines. These were to culminate in an ambitious and elaborate Bengali theatre production of Thomas Brasch’s play Frauen-Krieg-Lustspiel (Women-War-Comedy). The job of translating this rather challenging text from the German original was assigned to Suman Chatterjee, an erstwhile employee of the Deutsche Welle Radio, Bengali Service, in Cologne, who after returning to his native country had now become a celebrity singer of a new trend of Bengali thought-provoking, self-composed songs. The mantle of direction fell on Amitava Roy, who had earlier had a tryst with Günter Grass. Involving a stage and set designer from Germany, the production was mounted on a large scale in a vast open ground which was converted into an arena. The shows which ran every evening for five weeks on the trot attracted huge audiences, not only because of the play’s content but also on account of the grandeur of the sets.

Closer to the turn of the millennium and in the first decade of this century, interest in scouting for plays from European shores was on the wane.

The reasons for this could be any one of the following, or a combination of them

:

- Despite apparent irreversible globalisation the living conditions in Europe and India were vastly different, at least as far as the bulk of the middle class was concerned;

- Non-availability of immediate English translations of contemporary German plays as source material for inspiration and motivation;

- Technology had made huge incursions into theatre productions in the West, an area that local theatre practitioners did not dare tread on, given the uncertain local production conditions and the fact that none of the theatre groups had a theatre space of their own.

The praiseworthy initiative of the Goethe-Institut Munich’s theatre department in annually making a folio of selected contemporary German plays featured at the Mühlheimer Theatertage available in English translation, sometimes with video excerpts of the German productions, provided a very useful platform of primary resource material for interested theatre practitioners to delve into. In Calcutta, the outcome of this exercise was a very powerful translation and production of Marius von Mayenburg’s Feuergesicht (Fireface) which successfully ran for several shows over months in the Goethe-Institut Kolkata’s own theatre hall. It was thought-provokingly directed by the young director Suman Mukhopadhyay, who later endeared himself to audiences in Germany with two of his acclaimed films at the Munich International Film Festival in the year 2010, where they were presented as part of the section Country Focus India that year.

Let us fervently hope that this new initiative of the Goethe-Institut Mumbai to create a repository of translations of contemporary German plays into South Asian languages will trigger a renewed interest in grappling with and coming to terms with contemporary German plays among theatre practitioners in the subcontinent. We look forward to a very positive and meaningful outcome.