Translations unifying India

In the largest multilingual country

A new culture of translation could help unite the divided India: Mini Krishnan's commitment through the medium of literature.

By Martin Kämpchen

India is afflicted by multilingualism. In addition to the 22 official and scheduled languages, there are hundreds of dialects and dozens of tribal languages, many of them based on oral tradition, their treasures hardly discovered. When one speaks of “Indian culture”, one also means this overwhelming multitude of languages. None of these languages is dominant, no origin can be identified to which all languages and dialects can be traced back. Hindi predominates in northern India, but as soon as the government wants to make it the official lingua franca of India, it is bitterly contested, especially in southern India. The languages of the four southern Indian states bear little resemblance to Hindi. That is why, often with harsh resentment, English has to be used for general communication alongside Hindi. Politically, the conflict over the dominance and use of languages stretches to the point that regional governments collapse and coalitions are forged. Let us remember that East Pakistan split off from West Pakistan - both former parts of British India - under bloody fighting and became a separate country, namely Bangladesh, because the East speaks Bengali and did not wish to be imposed by Western Urdu.

It doesn't work without English

It doesn't work without English: As early as primary school age should Indian children learn the world language | © Anja Bohnhof

It doesn't work without English: As early as primary school age should Indian children learn the world language | © Anja Bohnhof

Do you speak Hindi?

As essential as English and Hindi are as second languages, the respective mother tongue constitutes an integral part of identity, precisely because India is linguistically so fragmented and educated Indians have to grow up multilingual in order to be able to communicate nationwide. The rural population has little chance of getting beyond their mother tongue. That is an essential element of their state of backwardness.

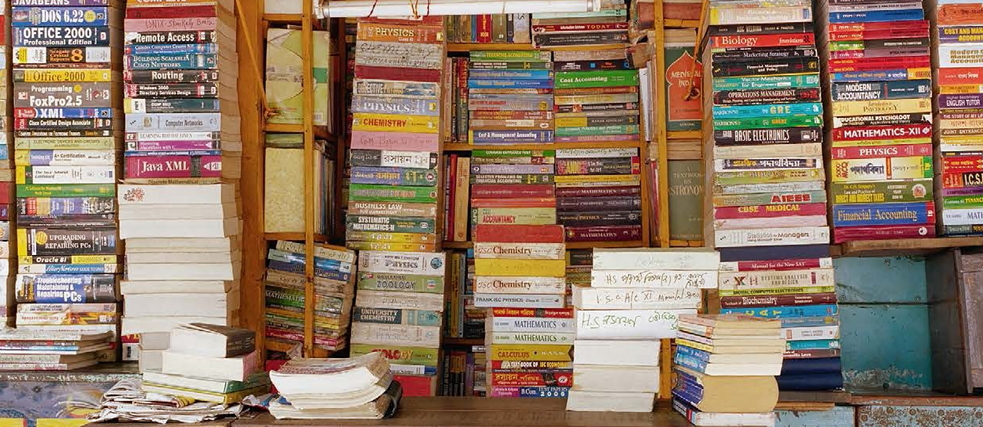

Regional writers have a hard time

Regional writers have a hard time: With their books, they are often limited to their language areas. | © Anja Bohnhof

Regional writers have a hard time: With their books, they are often limited to their language areas. | © Anja Bohnhof

The effort to make India's literature transparent to one another has only existed for a few decades. Over the years, more and more publishers have begun to have works from regional literature translated into English. The Indian Academy of Literature (Sahitya Akademi) is a pioneer thanks to its statute which obliges it to promote officially recognized literature. However, some large English-language publishers also took part. Initially, there was a lack of translators who could competently translate regional literature into English. In addition, the translation work was initially much less recognized and poorly paid.

Let us remember that Indian literature has only received a Nobel Prize once, and that very early on: in 1913 when Rabindranath Tagore was honored. Although Indian writers have been suggested again and again thereafter, the Nobel Prize Committee has not since considered worthy any other writers of this literature-besotted people. It would take some strong personalities, however, to help the project of Indian literary translation to assert itself in its importance for the self-image of the country and its international reputation.

One editor of translations who towers above everyone is Mini Krishnan. Born in Bangalore, South India, she learned the Malayalam language of her Kerala parents as a student. She calls herself “without roots” - perhaps a favorable prerequisite for finding translation as a life's work? The seventy-year-old now lives in Chennai (formerly Madras). As a result of forty years of tireless efforts to spread regional literature in English, Mini Krishnan has become the Grande dame of Indian literary translation. She dynamizes a process of national integration that goes far beyond its literary relevance and leaves traces in this multilingual society.

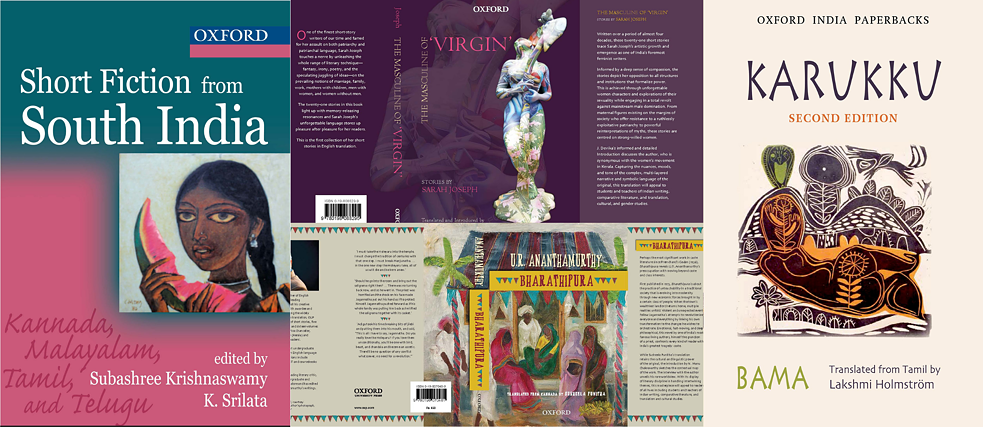

Making India's literatures transparent to one another

Making India's literatures transparent to one another: Mimi Krishnan has above all brought the so-called Dalit literature to light. | © Mini Krishnan

Making India's literatures transparent to one another: Mimi Krishnan has above all brought the so-called Dalit literature to light. | © Mini Krishnan

Her work is pioneering in all its facets. She has to look for translators for certain languages and certain authors, those who relate to the social milieu and the particular subject of the books. India's society is so diverse that the same translator could not accurately reproduce all the novels from a particular language. To a certain extent, Krishnan trains translators, checks their suitability, and usually calls in other translators or language specialists for advice. She does not make it easy for herself; Even more than within European languages, translation from Indian languages into English is a complex, creative endeavor. Krishnan describes a translation as a "Reconceptualization" of the original. Translators are co-creators of the literary work; she, therefore, gives translators greater freedom and responsibility than is customary in Europe.

Offering niche literature to the mainstream is a publishing risk that Mini Krishnan has taken time and again. Above all, she has brought so-called Dalit literature to light: she has had writers from the lowest castes, the tribes(Adivasis), who write authentically about their lot of poverty, discrimination, and contempt, translated into English from various languages. The novel "Karukku" by Bama, a Tamil author who portrays caste oppression within the Catholic Church, was so successful two decades after the original was published that the book made it easier to publish other Dalit novels.

The second focus of Krishnan is on women's literature, not only modern novels, but also historical biographies and novels. A significant success was Sarah Joseph's classic novel “Othappu” in Malayalam, which received an important literary award in English translation (“The Scent of the Other Side”). His sensitive subject is the fate of a nun who leaves her monastery and thereby causes a scandal. Translations should also bring works by Muslim and Christian authors into the focus of literary interest.

Mini Krishnan's intuition is revealed when discovering thematic gaps and hidden literary talents. She not only sees herself as a lecturer and editor, she also wants to promote literature in general. That is why she is on the road to seminars, literary festivals and as a member of various juries, constantly expanding her contacts and looking for new opportunities to network cultural and social India through translations. She was probably the first to have managed to publish a column on literary translation in the daily newspaper 'The Hindu', a topic that generally only interests specialists.

It is only too understandable that Mini Krishnan also faces limits: difficulties in marketing, limited funds, the sometimes futile effort to make publishers and readers aware of the importance of the project. The literary missionary proclaims, not without bravado: "If I had a million, I would commission a hundred translations, distribute hefty fees to the translators and writers, deliver the translations to the publishers and, like the Creator God command: 'Thou shalt publish!'"