Part One

BACK TO THE SKY

When I land at a new land, the first thing I do is look up at the sky. I measure my distance from home through the sky. I calibrate my sentiment for the new land through the sky.

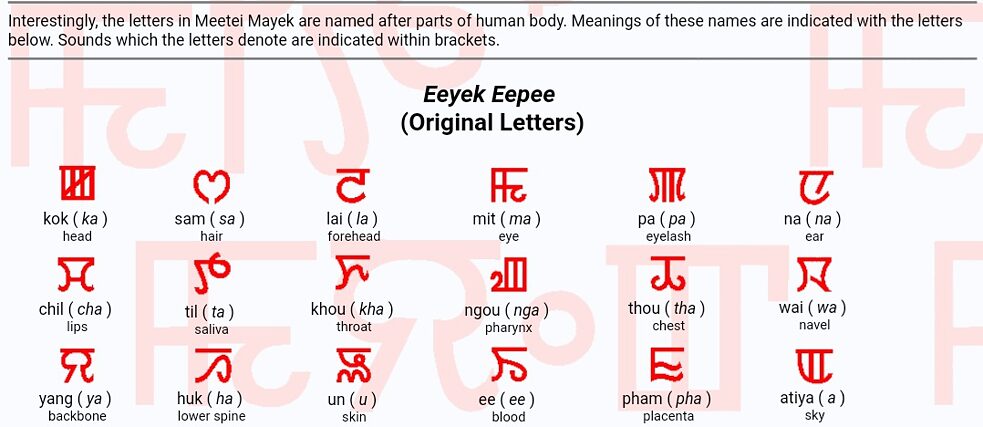

Sky is Atiya. Atiya is the last letter in the 18-letter alphabet system of Meetei Mayek, the script of Meeteilon, my mother tongue. All the first 17 letters are named after parts of the human body, starting from Kok (Head) to Pham (Placenta). My favourite personal interpretation of why Atiya is our last letter is this: we go back to the sky – our mortal bodies go back to the immortal space up there.

Why I went to Dresden has a lot to do with language, body, and atiya.

I am one of the bangaloREsidents-Expanded 2019, an initiative of the Goethe-Institut / Max Mueller Bhavan Bangalore. I did a 5-week residency at Zentralwerk, Dresden where I started work on my new project Yaang-Huuk-Uun: K(C)onfabulations. It uses the Meetei Mayek alphabet-to-body writing system to investigate the body languages and movements lost/transformed/polluted in social, cultural and political assimilation. I worked with the SouthEast Asian (SEA) community in Dresden – Asian restaurant & shop workers, teachers & students. Using a one-on-one performance conversation technique I’ve developed as my performance methodology, I used each alphabet-body part as a starting place to generate conversation about body movements in assimilation (known more as integration in Germany). I started mapping the small & big ways bodies forget/remember or lose/pick up things in the process of migration & assimilation. Meetei Mayek also acts as a mnemonic device. How fascism/colonialism/capitalism changes/erases/dismembers the body language/movement of politically vulnerable people is at the heart of Yaang-Huuk-Uun: K(C)onfabulations.

I will get to the details of my project in Dresden in my next article. This is a 3-part essay I am writing about my time and work in Dresden. We are at the first part right now.

We took the train from the Dresden airport. I was received by one of Zentralwerk artists D and his daughter E and her friend T at the airport. As soon as we got out of the Pieschen S-Bahn station and turned the corner into Riesaer Str. for Zentralwerk, I saw big patches of wildflowers hugging the footpath in a matter of fact, ordinary way. My first thought: this is good for the kids! I grew up in a hinterland with wildflowers and wild plants and as a child, the disorder of colours and shapes and smells and textures, and the different skin rashes I got from scrambling through the plant chaos cultivated my heart for active solitude and the world making of nonhumans.

The Zentralwerk courtyard is a HUGE quadrangle ringed by buildings of different sizes and style that the first thing I could really comprehend was the colour(s) of their walls. And when I saw this grand swing in the middle of courtyard, my delight shifted to it quite naturally. I later came to know that this was built during the TEH MEETING 2019 that happened in mid-May. TEH is Trans Europe Halles which is a “network of grassroots cultural centres” converting “abandoned buildings across Europe into vibrant centres for arts and culture”. It explained the stacks of event flyers I kept running into at the entrance of the main building.

Over my five weeks at Zentralwerk, I came to absorb the various histories of the buildings in bits and pieces. I didn’t actively pursue it. The stories seeped in through conversations – in fragments – and I let it be. I am averse to information overload about any place I am stepping into. Time and chance reveal a place more meaningfully, if one is lucky enough.

When I came to know that a sculptor designed the resident artist studio at Zentralwerk and many of her co-artists created this space together, I was able to put a finger on its atmospheric pulse. It looks out into another residential building and for the first time in my life, I came to know that at the sign of rain or sound of thunder, German aunties promptly bring out thin plastic sheets to shield their balcony flowers from the downpour. I never tired of watching the process – how the sheet is carefully held out and softly spread over the delicate flowers and gently clipped so that it won’t fly away.

My love for the studio was very simple. It fulfilled me – it was quiet, atmospheric, spacious, and there were neighbours’ balconies I could watch.

When I wasn’t working on my own, I spent a good chunk of time with K. A painter by training, K turned her studio into a temporary coffee room for us. We worked out a daily coffee hour. Working with her, talking with her, watching her new-born daughter, I was able to start grasping – gingerly though – the land of Dresden and the people of Dresden.

On the first day we met (my 2nd day in Dresden), she took me to the neighbourhood festival Sankt Pieschen where I found how the river Elbe runs like the backbone/spine of Dresden.

On my 3rd day in Dresden, Sunday 02 June 2019, I gave an artist talk to a group of artists working/living in Zentralwerk. I spoke about my past work and why I was at Zentralwerk. What I truly want to share again here is the trope I used to begin my talk. I used the trope of the Thijarian.

WHY? Because I come from a land whose annihilation happened while I was growing up and I was too young to know what and how to grieve. The work that I now make as an adult and identify as art is me bearing witness, across time and space, to my land and people who had perished.

Blood is Ee, the 16th letter in Meetei Mayek.

I work as a playwright, too. I read the British playwright Martin Crimp very carefully. In a long interview with theatre critic Aleks Sierz for his book The Theatre of Martin Crimp, Crimp was asked about drafts and workshops. In his answer, Crimp made one point that struck me, “There’s nothing wrong with workshops. But you need to be strong and experienced in order to benefit.”

After I completed my 5-week residency at Zentralwerk, what Crimp said made a completely new sense to me. The work that I managed to do in Dresden wouldn’t have been possible 10 or even 5 years ago for me. I wouldn’t have had the strength or experience to chart it out as clearly and as morally as possible. Zentralwerk is also the type of working artists’ space which requires a very different spirit to inhabit – I found it perfect for working in active solitude and observe the world making of a place newly foreign to me. I say newly foreign because Germany isn’t foreign to me. I lived in Munich more than 10 years ago. But Dresden isn’t Munich.

Here ends the first part of this 3-part essay. Like they say, to be continued …

Comments

Comment