Feminist comics

Instead of Flowers, a Florilegium

For today's International Women's Day, we recommend feminist comics by four female artists.

By Regine Hader

Snack

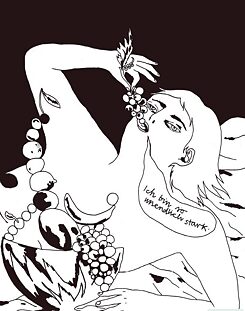

Even in ancient Greece, rumour had it that women and their pleasure were after all perhaps more powerful than the patriarchal fan-club of doctors, church and psychologists would have us believe inthe centuries that followed – or is this perhaps the very reason why so many have kept right on joining? Lina Ehrentraut's ten-page Snack explores the relationship of female pleasure, destruction and power, starting with a naked woman lying on her side eating grapes in the traditional art-historical manner. The comic does not create complex storylines or choreograph any grand arcs of tension. What Ehrentraut does capture in Snack, the way her protagonist slides unplanned from relaxed decadence with a fruit basket into self-empowerment and pleasure, works perfectly.Her dionysiac black-and white masturbation depictions play innovatively with perspectives and panel sizes, mixing filled surfaces and line art. With the latter, Ehrentraut picks up on current illustration trends in her idiosyncratic work. Snack is not only a successful homage to masturbation, but also to doodling, the untidy, the untamed. DIY wherever possible. Resistance is bursting out all over the place here, even from the conspicuously angular cursive she uses for the lettering. Reminiscent of zines or rebellious notes in a homework book, every single hook glaringly defies the dictates of harmony in a world of clean corporate designs and screams orgasmically: Obedience is dead! Empowering.

Shit is real

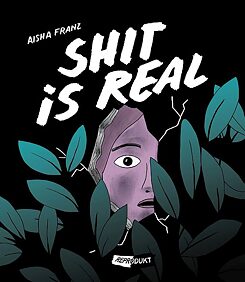

Shit is real is – in keeping with the title's phrasing – really hot shit! Aisha Franz's protagonists wear over-the-top, trendy party outfits, they are set in run-down off-spaces and kitschily furnished Asian restaurants - all of which tells lovingly of the Millennials' attitude towards life. Hardly any other comic captures so well how glamour and ironic trash combine symbiotically in this generation and how it feels to seemingly go through the whole range of possible human emotions between ordering and paying for a drink.In her drawings, Franz experiments with visual versions of personal narrative and stream of consciousness. As the figures become intoxicated, lines bend into small waves, oversized heads wobble with each step, tiny rubber bodies contort. With this trippy, psychedelic aesthetic, Franz translates visually the mood of an accelerated generation. Her images continually work on conventions of representation, traditional symbolism or seemingly avant-garde codes. She thereby also operates on a discourse level, commenting aesthetically on what actually happens on the histoire level, i.e. in the plot.

There she repeatedly interrupts the continuity by introducing simultaneity with dream-like scenes: The protagonist of Shit is Real survives in a parallel world outside civilisation. Here in the desert, where her girlfriend will later give birth to a latex egg, everything is so symbolically overblown that it reads like a case study by Sigmund Freud. Freshly separated, broke and depressed, she has ended up in this place because she no longer fits into her friends' environment. By being allowed to return only when she realises in neoliberal fashion that she is lamenting for no reason and that her happiness is in her own hands, Franz nonetheless renders the “real world” as equally distorted and plastered over with obscuring mirrors, dealing both ironically and playfully with contemporary social paradigms. The protagonist eventually steals an identity. Through the cool clothes, the parties and the minimalist flat, the lovable trickster character exposes both the classicist and financial barriers to this world that otherwise camouflage the grand freedom narratives of pop and subcultures.

Both the style and the story are reminiscent of the feminist Malmö comic scene, whose leading star Liv Störmquist astutely criticises patriarchy, capitalist and sexist systems of oppression. In it, she gives almost equal space to text and drawing. Franz differs from Strömquist's significant critique mainly through novelistic stories that are less obvious. She detects subtle intermediate and undertones, refrains from explaining jokes or polemicising. The mise-en-scene, the characters, the plot twist: everything about Shit is real means freedom without Franz spelling it out in big letters on the cover. The queer love story remains just as implicit. This queer-feminist world quickly picks up speed through increases and zooms, repeatedly violating the classic panel arrangement with relish. In moments of loss of control, the contours sometimes disappear completely, sometimes faces or enlarged sections of the picture push themselves over the geometric lateral order. They pull in a second level on which we encounter peculiar details.

Shit is real aims for a less incidental aesthetic. It celebrates pop, celebrates excessive artificiality. This is about surfaces. Materiality. Tactility. Fluid ghostly bodies waft across a roof terrace like clouds of smoke from a shisha, latex clothing reflects all over the club and even when the protagonist is watching TV on the sofa, the stained pattern of the bathrobe fights with the zebra look of the sofa blanket and the terry towel in her hair for every millimetre in the frame. Should anyone come up with the idea of colouring in this black-and-white comic afterwards, one thing has been clear for a long time: it has to be with neon markers! With this style, Franz is akin to somewhat lesser-known representatives of the Malmö School such as Moa Romanova, who sets new standards for techno and contemporary lifestyles in comics with her outstanding, innovative debut IdentiKid. Beyond the victim narrative, Aisha Franz tells of the strange thrownness into the world; of protagonists who wander between “sisterhood” and unspoken, queer love, and at least 70 percent of the time have an awful lot of fun in the process.

In Shit is real Aisha Franz takes up the vulva motif as she does in Brigitte oder der Perlenhort (i.e. Brigitte or the Hoard of Pearls). The deliberately striking vulva icons of recent years (which can be seen on Instagram either as jewellery, stickers or illustrations of the most diverse anatomical forms) aim to create visibility and reclaim phallically coded territories. Above all, however, they aim to and ensure that people finally stop thinking that women's genitals are to be exclusively referred to with “vagina”. Franz goes beyond that: she imbues these symbols with a function for her self-empowering narrative.

By the way, the illustrator studied at the Kunsthochschule Kassel, a forge of great comic artists in Germany. The anthologies of the comic class “Triebwerk” is, like everything from Aisha Franz herself: superb each and every time.

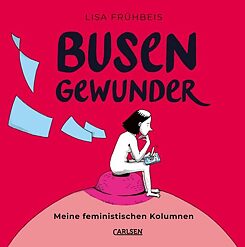

Busengewunder

In Busengewunder, Lisa Frühbeis addresses feminist issues far more explicitly. The volume gathers together her comic column for the Berliner Tagesspiegel. When you leaf through it, the debates of the last few years, from quotas to shaving dictates to the pill, are reviewed. Although the artist describes herself as a post-feminist, the selection of drawings clearly speaks of cis-sexuality in heterosexual relationships. But as we know, there is still a lot of catching up to do here.Lisa Frühbeis positions herself in the tradition of Mithu Sanyal's Vulva and Gabi Schweiger's Viva la Vulva by drawing side by side how vulval forms appear everywhere (even in religious iconography). When they line up next to each other, the objects reveal of themselves just how absurd the ambivalent relationship to female sexuality really is. Thanks to this dramaturgical elegance, the somewhat weaker drawings can be overlooked. At least as long as the figures and faces reminiscent of illustrations in language-learning books do not get out of hand. At some points, this schematism pursues a substantive goal, for example when Frühbeis discusses how little the diversity of breasts has been showcased in comics for far too long: As an ammunition-like attribute, they stand plump and militarily at attention – and of course women who don't have them aren't worth mentioning either. This is not new, but in Busengewunder it is very vivid, visually right to the point. Touchée! Frühbeis is not creating a feminist comic utopia and ignores those that already exist. Her merit is her political commentary on the not-so-utopian mainstream reality.

Unfortunately, her criticism of the limiting history of the portrayal of female characters and figures sometimes descends into downright bodyshaming: “It's me Twiggy. I have a body and skin like a ten-year-old,” reads a speech bubble next to the Sixties model. But Frühbeis adds insult to injury, spitefully drawing a speech bubble next to it and writing, “Really worth striving for.” Devaluing androgynous bodies in a heterosexist society and defaming them as “childish”? That's about as post-feminist and enlightened as the new season of Germanys next Topmodel.

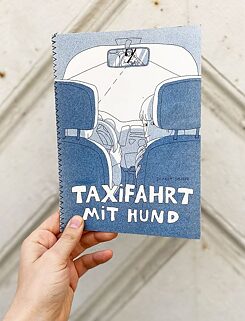

Taxifahrt mit Hund and Chivalry & Ennui

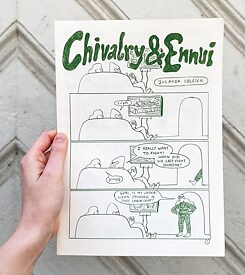

Like Aisha Franz, newcomer Jolanda Obleser studied at the Kunsthochschule in Kassel. Her comics are short stories, usually booklets of only a few pages, sewn together in cross-stitch or simply folded. In them, animistic fantasies almost always permeate the every-day situation with which everything begins.The levels mix in Chivalry & Ennui: Are we in the living room of an avatar flat-sharing community waiting for the next game to start? Or are we in a real flat-sharing community, where the flatmates slip into their adventurous roles at the console because real life is so incredibly boring?

Each individual character is fleshed out with unusual details, in this case a pretty chain-mail shirt. Those who don't understand why screenwriters first develop a character and then write the script need only take a look at Obleser's characters to understand. Much like Aisha Franz, she draws brilliant clothing with love and narrative flair. As soon as her protagonists appear in them, they are individual, perhaps ambivalent figures who are living through something. Obleser manages to put her readers into her protagonists' world. She captures the body language, the exact movements and then almost suddenly depicts their confusion. The characters are never leaden or rigid, but always portrayed in the “fertile moment”, that is, in the most suspenseful second just before something happens. This is how the stories pick up speed. The comics work in the smallest of spaces because the artist has an excellent command of composition and dramaturgy. The gamer, for example, is not merely there: a toe with a cut chain-mail shirt signals that she is about to enter the living room (and thus the next panel).

Whether Obleser is depicting a taxi ride with a dog (synonymous with “unsolicited free life assessment from the taxi driver with the quintessential message: Girls, your university studies are easy and totally pointless and you haven’t a clue about what's going on anyway”), or it's about women in video games: there's always a breeze of feminism blowing in Jolanda Obleser's world.

Lina Ehrentraut: Snack

Published in: Strapazin Nr. 141 (Dezember 2020) - Superheld*innen in der Krise

Aisha Franz: Shit is real

Berlin, Reprodukt, 2016. 288 S.

ISBN: 978-3-95640-063-6

Lisa Frühbeis: Busengewunder

Hamburg, Carlsen, 2020. 128 S.

ISBN: 978-3-551-79356-0

Jolanda Obleser's Comics are self-published.