Memory and Power

The Fictitious “Mãe Preta”

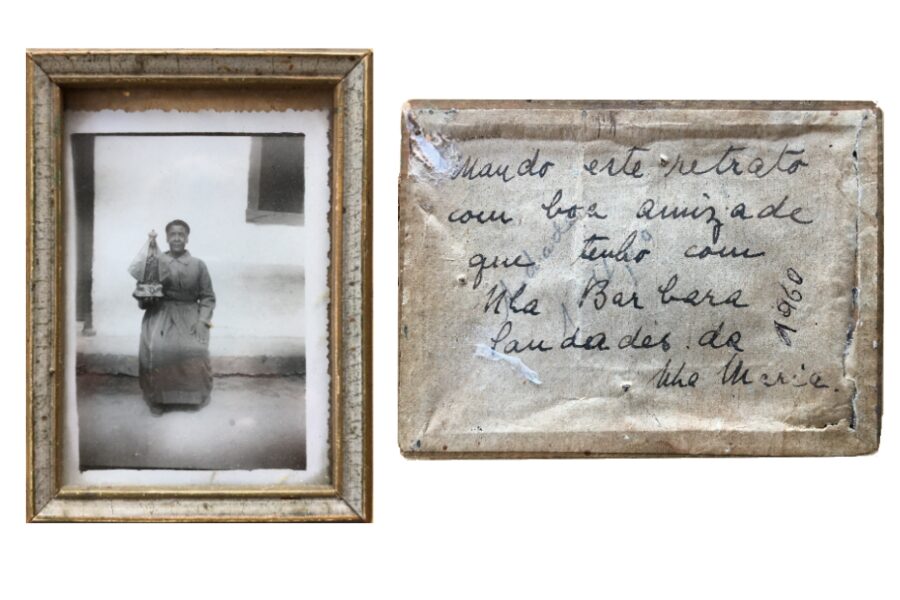

The photo of a Black woman on my white Brazilian grandmother’s kitchen wall gives rise to many questions. My grandmother calls the woman her “mãe preta”. But who was she really?

By Alma Kaiser

To what extent does absence suggest power structures? This question applies to a photo that always used to hang on my Brazilian grandmother’s kitchen wall, showing an elderly woman named Nhá Maria, referred to by my grandmother as her mãe preta – “Black mother”. My German family always imagined that Nhá Maria brought up my white grandmother, who – as the daughter of German immigrants – lived in Brazil until she was 21. However, conversations with my grandmother revealed that she hardly knew anything about Nhá Maria. Nhá Maria was neither a servant nor a nanny to the family. She simply lived in the same neighbourhood and, according to stories, was known locally for her healing powers and ministration. So, what caused my grandmother to call Nhá Maria her mãe preta?

Cultural theorist Stuart Hall has inspired me to seek the deeper meaning of the photo – and the arbitrary term mãe preta – in that which is not visible and about which my grandmother and family can only fantasise. The photo expresses the ignorance of the story of Nhá Maria. That ignorance forms the breeding ground for colonial ideas and carries them into the present. In order to disrupt the reproduction of colonial power, it is essential to track down white colonial ideas, expose them and thereby invalidate them.

The Urgency of Transformation

In the colonial establishment of Brazil, enslaved mothers were exploited twice over. On the one hand they worked on the plantations and in the master’s house, the casa grande. On the other hand, when they gave birth to a child of their own, they were enslaved as wet nurses for the children of their “masters”. The abuse of their motherhood – their milk and their affection – thereby assured the biological perpetuation of a society that was racist in structure. Furthermore, it is evident on photos and depictions of the mãe preta originating from the colonial era that the motif of the Black slave breastfeeding her little white “master” has been romanticised and fetishised. The figure of the mãe preta appears as a central element to the economic, biological and social production and reproduction of the colonial division of society.“The abuse of their motherhood – their milk and their affection – thereby assured the biological perpetuation of a society that was racist in structure.”

The Photo

An inscription on the back of the little frame reads in Portuguese: “I’m sending this portrait as a sign of my good friendship with Nhá Barbara (my grandmother). Fondly yours, Nhá Maria.” The photo, which was taken around 1960, shows an elderly woman sitting in front of her little house, looking into the camera with an expression that seems sad yet proud, holding a statue of the Brazilian patron saint Nossa Senhora Aparecida in her hands. Nhá Maria: the story of a woman, which was never told. | Photo: Private Archive Alma Kaiser

Nhá Maria: the story of a woman, which was never told. | Photo: Private Archive Alma Kaiser

White Fantasies

The photo that has been retained until today bears witness to a friendly relationship between a Black woman and a white girl in 1940s Brazil. At the same time, it tells of the ignorance of that woman’s history, because – as my grandmother herself observes – no one was interested in her during her lifetime. Ignorance – all those things we don’t (want to) see and hear – forms the breeding ground for fantasies about what we do see. In accordance with Stuart Hall I suppose that my grandmother in her ignorance regarding Nhá Maria was appropriating the colonial idea of the mãe preta to allow some leeway for her fascination with this elderly Black woman. The consequence is that my German family developed a sort of exotic legend about Nhá Maria being my grandmother’s nanny – although she never was.In her imagination my grandmother reduced Nhá Maria to three attributes: Blackness, femininity and spiritual ministration. According to Stuart Hall, reducing someone to their attributes like this is typical for the development of a fetish, which in turn is a common psychological – and unconscious – response to a taboo. Within the racist environment in which my grandmother and Nhá Maria lived, their friendship was taboo. I suspect that by unconsciously fetishising Nhá Maria as a mãe preta, my grandmother wanted to rationalise her acquaintance with a Black woman from the neighbourhood.

Because no one ever asked who Nhá Maria had been as a person, my grandmother’s colonial fantasy in relation to the photo was able to evolve into a legend until this day. The photo illustrates that no attention had been given to Nhá Maria’s real story. We don’t know what actually happened in her life. At the same time imaginations – fantasies – developed around her identity, which correspond to colonial ideologies that are thus carried into the present day. A more or less fictitious mãe preta, who de facto did not exist.

Traces

As long as we do not question the absence of Black women’s stories in white family archives, we are reproducing the colonial objectification of Black women in the present day. In that respect, friendship and closeness can mask the reproduction of power. Because the intimacy between the white baby and their enslaved wet nurse was central to the reproduction of colonial power, the use of the term mãe preta on my grandmother’s part to describe her friendship with Nhá Maria is problematic. Precisely because my grandmother doesn’t know Nhá Maria’s story, her use of the term reproduces the colonial romanticisation of oppressed Black women in Brazil.My analysis of her photo is a departure in a new direction: never again will this picture simply hang silently on a kitchen wall in Germany. Yet the photo still does not tell Nhá Maria’s story. Absent stories cannot be told by people who had no interest in – or even actively silenced – that person during their lifetime. This thought turns the photo into an archive of resistance: Nhá Maria’s story will always remain her own.

The article was first published in the edition “Macht“ of the Humboldt magazine.