Gender Mainstreaming

The Gender Aspect of Climate Change

The majority of the world’s poor are women, they rely heavily on natural resources to provide for their families and they have no access to decision-making processes in many areas of the world. Dr Shouraseni Sen Roy shows how women are significantly affected more by the consequences of climate change.

By Shouraseni Sen Roy

On May 26 2021, Cyclone Yaas made landfall on the east coast of India, inundating the adjacent low-lying islands of the Indian Sundarban Delta (ISD). It caused the destruction of the main yield of the season, rice. The local communities faced food insecurity and had to think about alternate sources of livelihood. Some of them are now forced to put themselves in dangerous situations such as crab collection, where they run the risk of being attacked by tigers or move out of their familiar surroundings to big cities in search of employment. This is a common dilemma being faced by vulnerable communities living in areas most impacted by climate change and extreme weather.

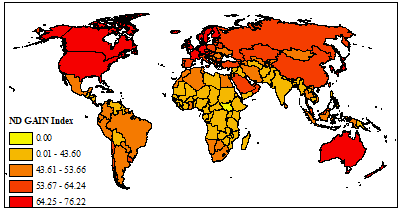

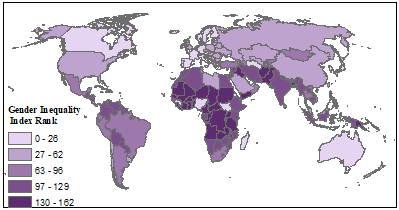

According to the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) the last four decades have been warmer than any of the preceding decades since 1850 and greater frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. The impact of the observed trends in climate processes has resulted in widespread damages to physical infrastructure and long-lasting impacts on the local economies. More importantly, climate change affects men and women differently. This is particularly true in the majority of the Global South, where gender inequality is worse due to lower levels of empowerment and limited access to resources. In most of Asia and Africa, the lower status of women and girls is caused to a large extent by societal norms, which in turn results in the disproportionately greater negative impacts of climate change on them.

The Consequences for Women and Girls

A majority of the world’s 1.5 billion people living on one Dollar a day or less are women, who rely most heavily on natural resources susceptible to climate change. In many cases, women also face greater social, economic, and political challenges than men, which limit their coping capacity.In rural areas, women are usually responsible for collecting water for families as well as fuelwood for cooking and heating. As a result of climate change related impacts, there is increasing deforestation and droughts, due to which women and girls often have to walk longer distances to collect water and fuelwood. As distances to water sources lengthen, women and girls become more vulnerable to various forms of harassment, violence, and harsher weather conditions in the form of high temperatures and heavy precipitation. Furthermore, with longer times devoted to these activities, these circumstances deprive young school-age girls of attending school and they fall behind in their studies. Over time, this often causes them to drop out of school and ultimately not be eligible for future employment opportunities.

In view of the traditionally limited role of women in decision-making processes at various levels, their needs, interests, and constraints are poorly reflected in policy-making processes and government programs aimed at poverty reduction, food security, and environmental sustainability. They also have lower access to financial resources. A greater proportion of women in poor countries engage in subsistence farming, exposing them more adversely to the effects of environmental degradation such as food shortages, poor health, and malnutrition.

In many of the larger metropolitan areas in the Global South, there is growing rural-urban migration because of the declining yields. This results in overcrowding in the cities and a clash of cultures, making women and girls particularly vulnerable to harassment, as evidenced in the recent increasing instances of violence against women in cities such as New Delhi, India. In addition, the young men leave behind the women in the countryside to take care of the elderly and children. Women and girls however are often the last to eat in the household, but because of the limited supply of food that leads to the widespread prevalence of malnutrition.

Informal Social Capital

There is increasing evidence of the direct and indirect role of climate change in triggering conflicts in various regions of the Global South, such as the current Darfur and Syrian conflict. Because of these conflicts, many people need to flee from their homelands and move to new unfamiliar surroundings making them extremely vulnerable. Reports of violence against women and girls in the temporary settlements are very high, and the dark figures are supposed to be even higher.Women are, in most cases, unable to build formal social capital, including decision-making processes, policies, and institutions, which deprive them when they require active support from social capital. In contrast, women have a much larger influence in building informal social capital, which immensely helps the entire society, males included, in addressing the aftermath of any climate-induced disaster.

The role of climate change on human health is well documented. As said, malnutrition and unhealthy conditions such as non-hygienic living conditions and indoor air pollution from wood or coal-burning stoves, are again particularly affecting women and girls. Furthermore, in most of the traditional societies of the Global South, women and girls are responsible for taking care of those who are unwell, which exposes them to transmitted infections.

The E3 Approach

Thus, it is clearly evident that women and girls in the Global South are disproportionately affected by the already occurring and impending impacts of climate change. In this context, it is critical to bring more balance and make progress for the overall society, through the integration of a gender perspective into the preparation, design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies. In order to achieve this widespread gender mainstreaming, I suggest the E3 approach: Enumeration, Education, and Empowerment.Enumeration: One of the major obstacles in accurately assessing the impacts of climate change on women and girls is the absence of gender disaggregated data collection. Gender and age disaggregated quantitative data are helpful in generalizing information for a larger population about differences based on gender and age.

Education: One of the best investments for the overall progress of society is in girls’ education, health, and safety. Investing at an earlier age ensures that they grow up as more aware and empowered human beings, who can not only speak for themselves but can also, care for their families. This ensures the overall long-term well-being of society. It is estimated that an extra year in primary school can result in increased adult wages of 10 to 20 percent, which increases to 15 to 25 percent because of an extra year in secondary school. Given the projected climate changes, the time they spend on these daily chores will only increase, so they will spend less time in school.

Empowerment: Not only is it important to address gender inequality in the Global South but there needs to be much more discussion about women's empowerment in terms of adaptation and mitigation strategies. The lack of power and limited access to financial resources puts women at a disadvantage to adapt to the impacts of climate change. Nevertheless, there is widespread evidence of the critical role of women in the conservation and reforestation efforts, particularly in the rural areas of the Global South.

Educating and empowering girls from an early age will not only reduce the gender gaps in general but also help create awareness among future generations. Creating more gender-sensitive initiatives will result in more awareness and understanding of the general well-being of the entire population. The gender gaps can be reduced by adopting an explicit gender-sensitive approach in policy development at all levels. Without that, the marginalized and the poor, the majority of whom are women, will be more and more disadvantaged. Involving them in the decision-making process related to land management and agriculture will ensure greater food security and better overall health of the family. The benefits of gender mainstreaming can undeniably contribute to climate change adaptation and the prevention of its negative impacts.