Life in Paris

Eight Rather Happy Years

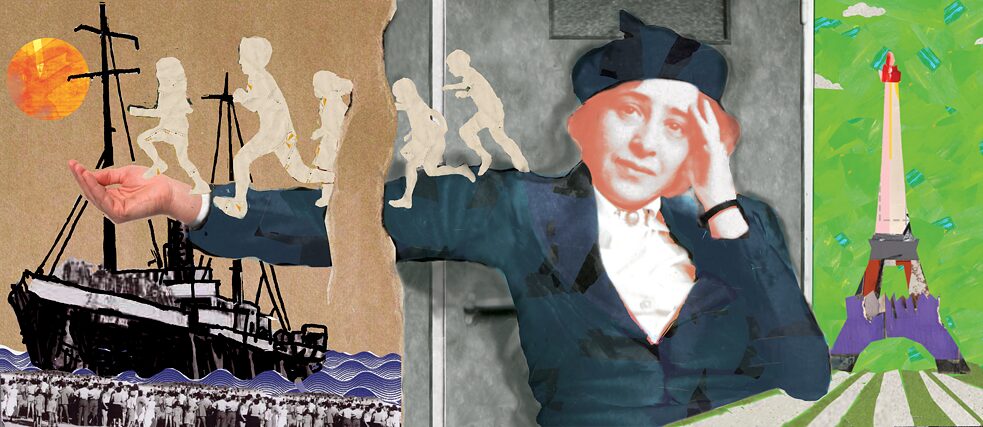

In 1933, Hannah Arendt left Germany and fled to Paris. The eight years she spent there before emigrating to the United States had a profound impact on the life and work of the political theorist. Yet for a long time, researchers largely overlooked this period of her life.

By Gina Arzdorf

When Hannah Arendt emigrated to Paris in October 1933, she was determined to leave behind for good the academic circles she had moved in during her studies in Marburg and Heidelberg. For the 27-year-old, it was too painful to watch Martin Heidegger – the man who had been both the first great love of her life and a pivotal figure in her philosophical education – embrace National Socialism, joining the Nazi Party in 1933. Confronted with what she saw as betrayal, Arendt resolved never again to “touch any kind of intellectual history”. Years later, in 1964, during her most famous interview with journalist Günter Gaus, she reflected on this turning point: “The personal problem was not what our enemies did, but what our friends did.”

Activist commitment

Indeed, the eight years Hannah Arendt spent in France were not those of contemplation. As the political climate darkened and antisemitism in Germany intensified, mere reflection was no longer an option. She firmly believed: “When one is attacked as a Jew, one must defend oneself as a Jew.” So in Paris, Arendt worked for several Jewish relief organisations whose mission was to prepare young German Jews – arriving in the French capital in the 1930s with little hope for the future – for emigration to Palestine.For a long time, scholars paid little attention to Arendt’s years of social work, or to her time in France more broadly. Yet what she lived through between October 1933 and May 1941 not only shaped the course of her later life, but also laid the groundwork for her writings in the United States. Her direct experience of antisemitism and its history, which she began to study in Paris, underpin the first chapter of her seminal work, The Origins of Totalitarianism. In France, Arendt also experienced firsthand what it meant to live without freedom. When German troops invaded in May 1940, she was deported as an “enemy alien” to the internment camp at Gurs in southern France, from which she was released a month later. Two years after fleeing to the United States, she recalled in her essay We Refugees how she and her fellow German exiles had “for seven years played the ludicrous role of people trying to be French” – only to be interned as Germans at the outbreak of war, despite having long since lost their German citizenship.