Unfiltered Thoughts

The Banality of Smoking

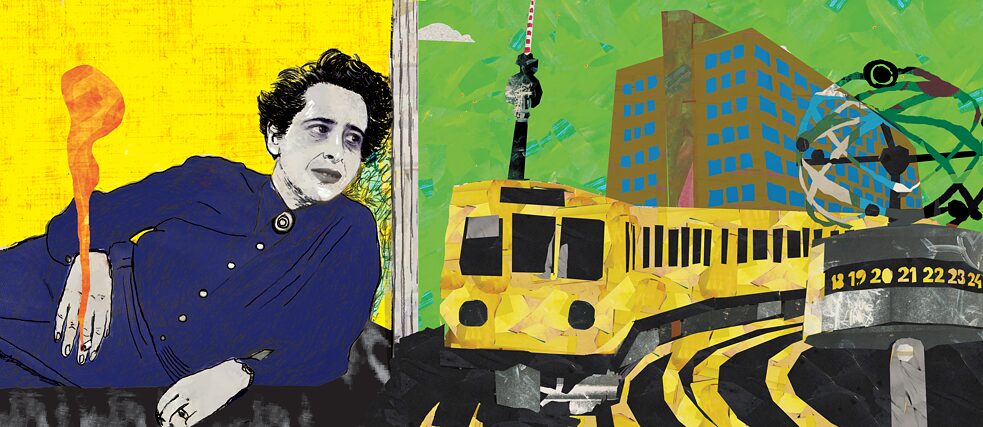

Hannah Arendt was a smoker – as countless iconic photographs reveal. Katharina Holzmann asks how this simple ritual shaped the philosopher’s thinking.

By Katharina Holzmann

Some images sear themselves into the collective memory, like the lingering smell of cold cigarette smoke on old pub curtains. One such image is that of Hannah Arendt at the speaker’s lectern, cigarette in hand. Her eyes half-closed, she gazes into the distance, wearing the detached expression so many assume when drawing deeply on a cigarette, inhaling the smoke and then releasing it in a slow, controlled exhale. Arendt was one of the great philosophers of the 20th century, known for her precise language and intellectual boldness. But she was also – let’s be honest – a chain smoker. This article seeks not to mock or ridicule, but to pay homage. Because sometimes, it seems, smoking can actually stimulate reflection. Or perhaps it’s the other way around.

Smoking today: uncool, unwise, unwanted!

The consumption of tobacco products somehow isn’t cool anymore – and certainly not sensible. Light up in a group of people, and you’re met with that peculiar mix of pity and silent judgement from those around you – as if you’re crossing a busy street as a child watches on. Modern life demands that we humans be on a mission: to remain as productive, optimised, radiant, pleasant-smelling and unobtrusive as possible – a kind of all-weather capital asset on two legs, poised for the next productivity boost. Any minor disruption to bodily functions, emotional balance or even collective well-being is deemed a faux pas. Smoking violates these new health rituals; it smells, suggests lethargy and runs counter to all trends towards self-optimisation and efficiency. Each drag feels like a pact with a shadow that slowly creeps into the lungs, settling in the delicate alveoli, dimming the pure light of breath; a thief gradually sapping strength from our muscles and stealing freedom from every inhalation. How often do friends tell me how much better their life is since quitting! They drink less alcohol (to avoid smoking), choose green tea over coffee (to avoid smoking) and spend more time exercising (because they no longer waste it on smoking). I simply smile and nod, fumbling in my pocket for my lighter. It’s not about coolness – I’m past that age. Physical addiction plays its part, certainly, but it’s more about mindset. My theory is this: smoking stimulates thought because it creates a physical and mental pause; conversely, thinking prompts smoking because intellectual effort requires a ritualised form of relaxation that smoking provides. Those who think may smoke less, ask more questions and perhaps try a little harder to understand this world.Instrument of reflection

At an exhibition about Hannah Arendt, one of the objects on display was her silver cigarette case – which was shown not as a fashion accessory but as a work tool. I imagine her placing it on the table, opening it, removing a cigarette, lighting it, inhaling the smoke – and at that very moment, allowing her thoughts to flow. It’s a pause that feels almost ceremonial. Perhaps the cigarette was not merely a habit for Arendt, but an instrument of reflection. The act of smoking creates a rhythm, a cadence in which ideas can emerge: a brief pause, a deep inhale, an exhale – and in that tiny interlude, something essential emerges from the complexity of the world.Altered state of consciousness

Not long ago – it can’t have been that long because I still recall smoking compartments on ICE trains and a rather unsavoury McDonald’s on Berlin’s Schlossstraße – smoking was less frowned upon in intellectual circles. In fact, you could almost say it was part of the “casual thinker’s” essential toolkit. In cafés and universities, in salons and seminars, the blue-grey smoke was a familiar companion to red wine, coffee or absinthe. It did look rather cool, I think – everyone sitting around, smoking at Frankfurt’s Café Laumer, Berlin’s Romanisches Café or, for that matter, Café de Flore in Paris. But it would be overly simplistic to reduce this atmosphere to mere tobacco marketing. For Hannah Arendt’s work, the act of thinking seemed to naturally and necessarily involve an altered state of consciousness: psychoactive substances can alter perception, both sensory and cognitive. Every seemingly mundane observation, every thought, can form new connections; associative and unconventional thinking becomes possible. Smoking can be a solitary pleasure, but it gains a new dimension in a group. When two or more people step outside together, a kind of temporary privacy emerges. Suddenly, there is space for an intense conversation, almost conspiratorial, because at least one thing is shared: the cigarette. For a few drags, thoughts either cease circling – or they resonate anew, now moving between the cigarette in one hand and the words of the person opposite. And sometimes, you simply stand silently side by side, absorbed in the act of exhaling smoke, painting a grey veil into the air, while watching the world drift by in that fleeting moment.Courage to be unconventional

It is a ritualised pause, a moment that holds the world at a distance, even when you’re not alone. Totalitarianism can only be examined from afar; and so the cigarette becomes more than a symbol of physical decline or risky indulgence – it embodies courage. Courage not just to think unconventionally, but to live unconventionally, to find one’s own rhythm in a world that constantly demands conformity. Thinking is not always heroic or abstract. Sometimes it’s banal, tangible, smoke-filled. The everyday and the profound, the human and the philosophical, the reach for a cigarette and the reach for ideas – they are closer than they appear.And if, today, you catch a whiff of stale cigarette smoke, don’t be irritated. Pause and think of Hannah Arendt, standing there, shaping life and thought like drifting smoke – unconventionally, unforgettably. Doing exactly what philosophers must do: think, breathe and never stop asking questions.