Loss and Reinvention

“There Is Much Talk about Death, But Not as Much about Mourning”

In some Afro-Brazilian religions, certain funerary rituals cannot be shared on social media. Among indigenous communities, traditions associated with death were made invisible due to the virus. In Brazil as a whole, there was more talk about the number of deaths than about ways to mourn them.

By Ana Paula Orlandi

Brazil lost six hundred thousand lives to COVID-19. Due to health measures, the act of dying became more solitary - with inadequate goodbyes and without traditional rituals like wakes. “The novel coronavirus pandemic brought even more difficulties to this moment which already wasn’t easy,” psychologist Maria Júlia Kovács points out, a professor at the Institute of Psychology at the University of São Paulo and founder of the Death Research Laboratory.

According to Kovács, mourning is a process of elaborating a significant loss. “One example is the death of people with whom we have connections. Meanwhile, there are other losses which do not result in death, but still bring a great deal of suffering because they disrupt our sense of normalcy, for instance getting sick, losing a job, or having to leave one’s country of origin,” the expert explains. “In the pandemic, we are living a series of mournings that come with significant loss to various degrees, like finding it impossible to do daily things while social distancing.”

In a pandemic scenario, Kovács reminds us, even those who have not lost someone to the virus with whom they were close end up stricken with a feeling of collective mourning. “It is a feeling of sorrow and solidarity with the sadness of people who have lost someone or who are suffering from COVID-19. At least, that is what we should feel in a situation of immense tragedy like the one we are living through in the country and in the world, but, unfortunately, the impression we have is that many people could actually care less about someone else’s pain,” the psychologist says.

Social Cohesion

In the opinion of anthropologist Denise Pimenta, Brazil did not manage to experience this collective mourning during the COVID-19 pandemic. “This because of a denialist narrative created by the federal government, which, among other things, is more concerned about the economy than with care. Collective mourning takes shape very much because of public health campaigns that show that everyone’s life is important and, therefore, each person’s death is going to be lamented by society. Today, there is much talk about death in Brazil, but not as much about mourning and lamenting so much loss,” Pimenta observes.The anthropologist is the author of the doctoral dissertation O cuidado perigoso: tramas de afeto e risco na Serra Leoa - a epidemia de Ebola contada pelas mulheres, vivas e mortas (Dangerous Care: Stories of Love and Risk in Sierra Leone - the Ebola Epidemic Told by Women, Living and Dead), which she defended in 2019, at the University of São Paulo. During her research, she spent nine months in the African country just after the end of the epidemic, which occurred between 2013 and 2016. “Sierra Leone’s population was very distraught by the deaths caused by Ebola because the local government managed to establish a narrative of collective mourning. At the time, greater social cohesion came out of that struggle,” the scholar recounts.

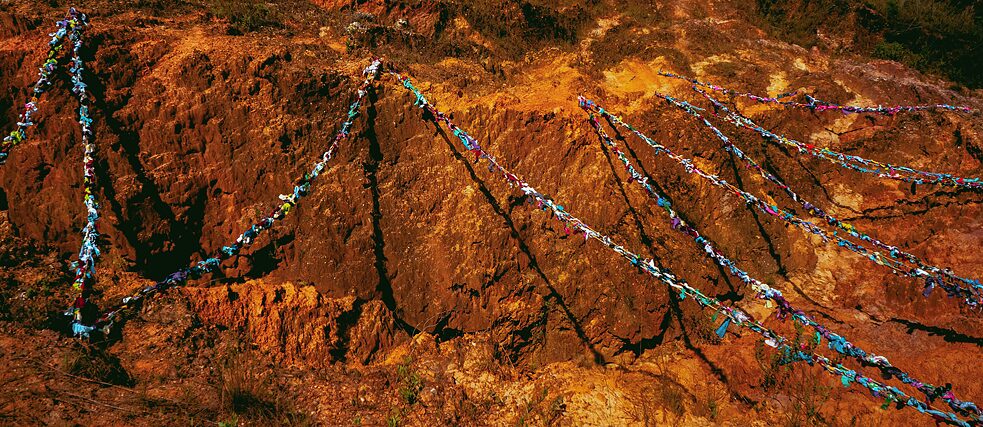

Pimenta reminds us that mourning is a collective phenomenon, where pain about loss needs to be shared with relatives and friends. “There are various rituals. In some communities, women cry or scream to symbolise the passage to death. In others, a string is cut, or something is left on the grave, for instance. It is one way to understand that that person is going, being taken away, that ties have been broken and new ties need to be made,” she observes. “However, during pandemics and epidemics, those rituals are suspended. We cannot meet one another, we cannot perform this mourning, ritual practices collapse, which are very important for what we are going through, for what we are feeling. This is deeply unsettling for people.”

A Biopolitical Virus

Regarding Brazil specifically, the ways people mourn are varied, according to anthropologist Emerson Sena, a professor who trained in the Science of Religion at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora. “Funerary rites in rural Brazil, which are still very influenced by mainstream Catholicism, are profoundly different from urban rituals. In rural areas, before the COVID-19 pandemic, wakes were held at home and had a whole moral and religious code to adhere to. The relatives of the dead would stand around the casket in concentric circles that radiate toward the kitchen where the guests would tell picaresque stories about moments in the deceased’s life. These rituals, obviously, have been temporarily suspended because of the COVID-19 syndemic,” he says.In his academic talks and articles, the anthropologist prefers using the term “syndemic” instead of “pandemic.” This is a concept, defined in 2009 by American anthropologist and doctor Merrill Singer, which seeks to understand illnesses based on biological and sociocultural determinants. “So, like the black plague (1346-1352) and the Spanish flu (1918-1920), the situation we are living with COVID-19 tends to generate profound change in cultural and practical terms as well as ideas. It is a biopolitical virus,” Sena says.

Between the Sacred and the Virtual

According to historian and anthropologist Andréia Vicente, a professor at Western Paraná State University, habits associated with death have transformed in the past because of pandemics and epidemics. “Cemeteries have been moved away from churches. They have been institutionalised, and they have become walled. The dead have come to be buried in closed caskets, under a specific amount of dirt,” the researcher says, an expert in death.Today, the story is not different. “The impossibility of being able to perform rites that help us to deal with death, like wakes and burials, brought a great deal of resentment to people who were nevertheless coming up with other ways to ritualise this moment. And this is still happening, especially on social media,” the scholar observes. “These media tools were already present in churches and temples, but, with the syndemic, their use has intensified,” Sena states.

According to Vicente, funeral homes, even those located in peripheral regions and in the countryside, are currently investing in audio and video equipment, besides improving internet access. “I think that type of innovation is here to stay including once the pandemic is over. For one, it allows a person who is unable to attend a funeral because of geographical distance to participate in the ritual remotely,” the researcher says.

Indigenous Rituals

However, the virtual world cannot span all death-related rituals, as is the case of some associated with indigenous peoples. “Among the Yanomamis, for example, the funerary ritual consists of ingesting the ashes of the dead in order to distribute the energy that the deceased enjoyed in life among those who remain in terrestrial life. This became impossible in cases of indigenous victims of COVID-19 who were brought to hospitals and buried in public cemeteries in cities,” Vicente says.Concerning other impediments to the relationship between the divine and the virtual, Sena recalls: “In some religions, certain rituals are so intimate, meant exclusively for initiates, that they cannot be shared openly on social media,” the expert notes. “That is the case of Axexê, a Candomblé funerary ritual, where you have to demarcate the border between the sacred world and the profane world.”

It’s not only today that our relationship with death and mourning is changing “There are those who say that mourning was already in crisis even before the COVID-19 pandemic. But I do not agree with that idea,” Vicente contends. “What we have today is a transformation of institutional mechanisms of mourning. Since the Middle Ages there has been a series of very rigid funerary norms, dictated by the church, that established how people had to experience mourning, for example the obligation to use black clothing or the commemoration of a seventh day mass. Today there is flexibility regarding how this is done, more in line with what the one in mourning wants,” he concludes.