Children and Adolescents in India

Lockdown and Its Mental Health Impacts

The pandemic has been particularly hard on children. Indian journalist Nimish Sawant writes about the consequences of lockdowns on the smallest in our society. Which impact do school closures and the ban of social contacts have? He looks at behavioural changes and disorders, while the full impact of the lockdowns on children continues to be researched.

By Nimish Sawant

Even before the Indian government announced a nationwide lockdown on 24 March 2020, many schools were already asked to shut down by 16 March. As a result, physical attendance in schools was out of the question until late 2021.

At a developmental age where contact with the outside world is necessary, not just for social, but also mental well-being, many children in India were stuck at home. Even as the lockdown restrictions eased up by October 2020, children had to face a profusion of changes in their everyday lives.

Effects on Mental Health

Lockdowns effectuated uncertainties such as social isolation, increased screen time and grief because of the loss of family members due to COVID-19-induced complications. According to Indian researches like Rishi Kumar, Prateek Kumar Panda and Juhi Gupta, depression, irritability, boredom, and fear of contracting COVID-19 were increasingly frequent for children and adolescents.Ahmedabad-based Preeti Das, a teacher by profession and mother of an eight-year-old, believes that the lockdowns definitely took a toll on her child. “Psychologically, it is affecting him. He has become more aggressive, cranky, and has developed certain tics in the last three to four months. We consulted doctors who told us that they see many such cases. It’s a manifestation of the emotional disruption children have been experiencing,” said Das.

Dr Anjana Thadani is a developmental pediatrician who counts children with special needs among her patients. According to her, the first few months of the lockdown meant a complete disruption in the medical support for children with special needs such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism, and so on. “This led to sudden spikes in their behaviour. It was only in June 2020 that most children who were on therapy started coming for online sessions,” noted Dr Thadani.

The pandemic reduced social interaction to a minimum, with fatal consequences especially for children. | Photo (detail): © Adnan Sharda

The pandemic reduced social interaction to a minimum, with fatal consequences especially for children. | Photo (detail): © Adnan Sharda

Impact on Adolescents

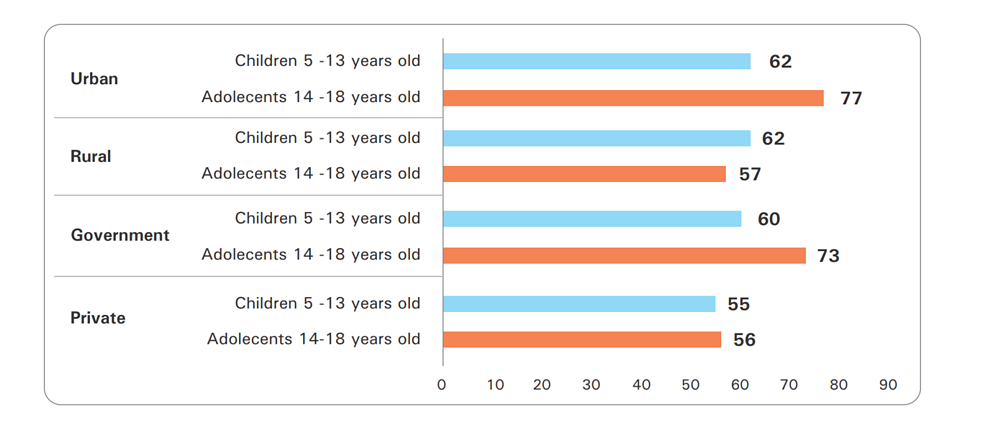

Children over the age of six could understand things such as covid protocols. According to Dr Thadani, many experienced grief either within the family or seeing images on TV. “As a parent, you have to tell children the truth. There was no escaping from bad news. There was always news about family members or neighbours contracting COVID-19. You just had to remind children why it was necessary to wear masks and maintain hygiene,” said Das, who was herself affected with the virus in April 2021 during the deadly second wave in India. UNICEF did a rapid assessment survey across six states in India with a sample size of over 6,000 parents, children, adolescents and teachers. Here is the response to the question: “Has (name) accessed any remote learning content or resources to learn while schools were closed in the last three months?” | Illustration (detail): © UNICEF INDIA

UNICEF did a rapid assessment survey across six states in India with a sample size of over 6,000 parents, children, adolescents and teachers. Here is the response to the question: “Has (name) accessed any remote learning content or resources to learn while schools were closed in the last three months?” | Illustration (detail): © UNICEF INDIA

Dr Naina Picardo, doctor and professor for otorhinolaryngology at Christian Medical College Hospital Vellore, believes the lockdown has had an impact on social as well as knowledge-based skills. “It's been noticed that social skills have regressed among children across all economic backgrounds. This can have long-term impacts in a child’s development,” stressed Dr Picardo.

Offline and Online Violence

Parents were already under stress due to economic insecurities and the pressures of working from home and managing the households amid the lockdown protocols. As a result, the mounting frustrations were witnessed by children.Childline India Foundation, which has a dedicated helpline for children in distress, noted a spike in calls pertaining to abuse and violence on children. Within the first ten days of the lockdown in 2020, Childline received over 92,000 calls related to violence against children. Since the pandemic, they have seen a 50 per cent spike in calls. In the online sphere as well, children were the target of many cybercriminals.

According to Das, spending so much time online also exposed kids to unwanted areas of the internet. “One drawback of online classes was that we noticed our child accessing Youtube videos which were not appropriate for his age. This is a nightmare for parents and you cannot afford to be a helicopter parent during such time,” said Das.

The digital inequity in India is apparent from the graph above where parents surveyed voted for internet recharge costs and device affordability as the major challenges in children’s education during the pandemic. | Illustration (detail): © UNICEF INDIA

The digital inequity in India is apparent from the graph above where parents surveyed voted for internet recharge costs and device affordability as the major challenges in children’s education during the pandemic. | Illustration (detail): © UNICEF INDIA

According to Dr Picardo, this inequity has an impact on the academic knowledge skills. “For children from well-off families, there hasn't been as much of a loss when it comes to education. But those who come from economically weaker backgrounds, will definitely lack in academic skills.”

Beyond Education

Another aspect of school shutdowns paired with the economic weakness of families and had a direct impact on children’s nutrition. For example, in India, the mid-day meal programme, launched in schools in 1995, is considered the most extensive school-feeding program globally and helps reduce calorie deficiencies in children by 30 per cent.According to a UN report, due to the COVID-19 lockdowns, around 100 million schoolchildren missed their meals till February 2021. This meant many children from marginalised families were deprived of nutritious food, which affected their cognitive abilities. According to government numbers from November 2021 place 1.8 million children in India as severely malnourished. According to the Global Hunger Index, India ranked 101 out of 116 countries in 2021.

In many states where schools were shut, take-home rations were being sent. However, Puja Marwaha, CEO of CRY India, notes that this wasn’t the most effective solution. “If earlier a child was allocated so much food, she was the only one who had it when she was in school. Now, it is going to her home, where there is already hunger, so her access (to food) is definitely compromised. Nutrition has an impact on mental health and growth,” noted Marwaha.

A major chunk of children now have a fear of returning to school. “This is a fear of falling severely sick. It will take time for children to adjust to going back to school. Most of the schools have opened in a hybrid format, so the transition is going to be slow,” said Dr Thadani.

Lost Youth and Childhood

According to Dr Picardo, the lockdown has definitely resulted in lost youth and childhood as children were stuck at home. “During growing years, as long as there is stimulation at home, that's good - even at the cost of not going to school. But during the lockdown we have seen children becoming comfortable with spending long hours on phones and being in their own world. This creates an attitude where they think they don't need the outer world. There is a lot of lost childhood there. For college going kids, they have missed out on an exciting part of their academic lives due to lockdowns,” noted Dr Picardo stating that this lost time will have a social impact on them.But, not all is lost. Barring children who were already suffering from health issues before the pandemic, Dr Picardo is of the opinion that children will catch up on the lost pandemic years in terms of social and knowledge skills.

Literature

- Psychological and Behavioral Impact of Lockdown and Quarantine Measures for COVID-19 Pandemic on Children, Adolescents and Caregivers

- UNICEF rapid assessment survey

- Childline India Foundation helpline calls

- UNICEF report on learning loss in South Asia

- Malnourished children in India

- Interview Puja Marwaha