Arguments for a Cultural Transition

The Digital Stage in India

Theatre, dance, music, art, film or literary festivals - the pandemic has forced the creative sector to rethink its relationship with the digital realm. Why going digital is not a bad approach for cultural practitioners in general, explains Indian cultural entrepreneur Rashmi Dhanwani in the following contribution.

By Rashmi Dhanwani

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect the creative economies of countries across the world. In India, the British Council, Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), and Art X Company have been tracking the deepening impact of the pandemic through their three-part survey series Taking the Temperature, which was completed by 742 respondents from Indian art organisations and professionals. The second survey, released in early 2021, studied the escalating crisis and highlighted survival risks for the culture sector in India.

It reports that 67 per cent of the surveyed respondents are uncertain that they can survive for more than a year with current resources and funding; 90 per cent of the respondents fear the long-term impact of social distancing on the creative economy; 60 per cent of the respondents believe it will take nine months to over a year for early signs of recovery for the creative economy. The creative economy is contracting with 16 per cent of the creative sector facing permanent closure. Cultural organisations are closing permanently to avoid bankruptcy. 22 per cent of the sector is forecast to lose more than 75 per cent of the annual income. Individual professionals and artisans are facing short-term hand-to-mouth existence even as sectors are adapting to digital and live business models to stay afloat.

In India, the culture sector does not have a culture policy, has negligible training in arts management, is informal in nature, and often relies on its own ingenuity to survive. In the pandemic times, as the warning bells were being sounded, there was a new push to digitise offerings. Digitisation, however, comes with its own challenges.

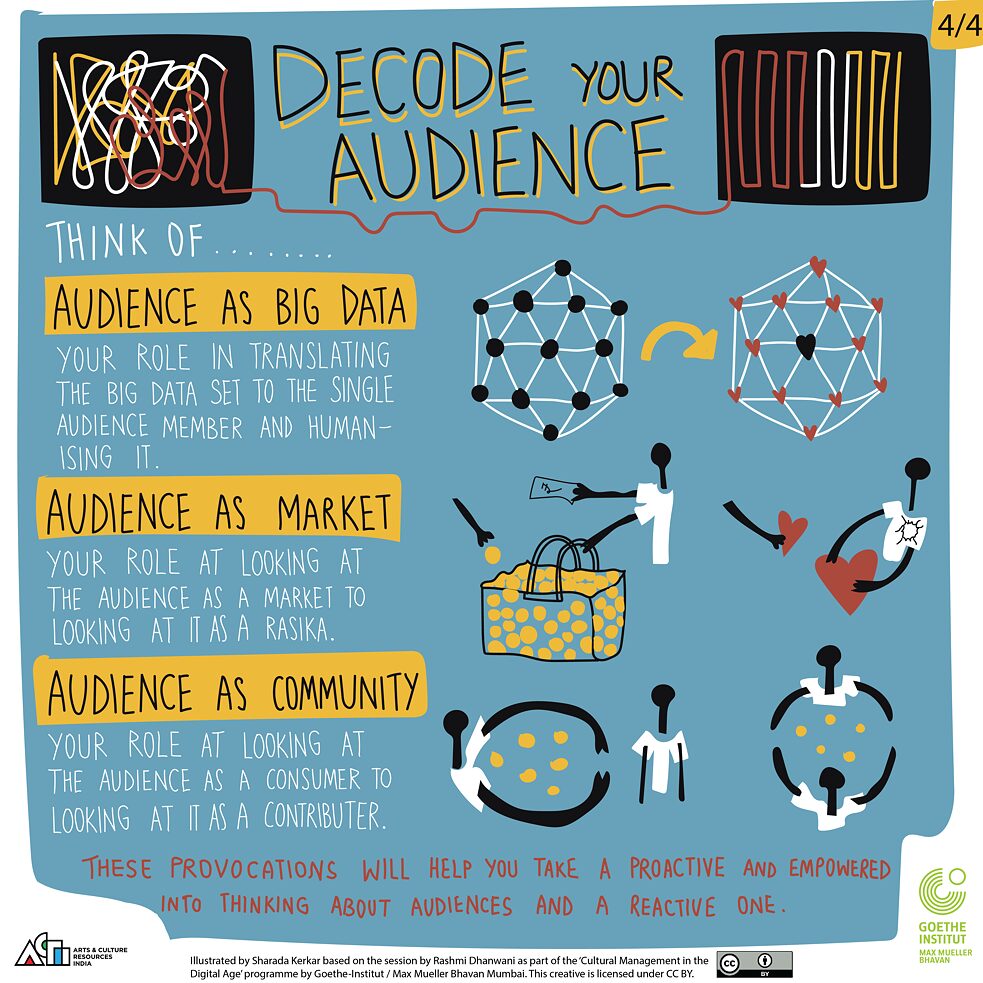

One is assuming that digitisation equals democratic access. Access to digital infrastructure and devices differs by location, gender and socio-economic status, thereby the need to know how to attract more audiences digitally. Another concern is the inadequate reflection on machinations of big tech and its impact on aesthetic and social autonomy. Digital platforms are designed for varied reasons, and digital offers are generally adapted to them. For instance, Zoom was designed as a meeting platform, which was further used to create “digital theatre”. Most new digital spaces are not custom designed for digital cultural activities and events, leaving arts and events managers to experiment, resulting in a high learning curve.

Getting more audience in the digital realm

The onset of the pandemic was both an opportunity and a threat. The threat of losing audience, jobs and livelihood due to restrictions on physical events. And an opportunity to rethink culture. Devising new ways of reaching the audience whilst maintaining the charm of cultural offerings.The literature festival Tata Literature Live, held digitally in 2021, sets an example on how the digital relations with an audience can be build or strengthened. The festival announces its dates on Instagram and a friend of yours shares it with you and influences you to sign up. If you like reading and are motivated to sign up, you would open up your device (mobile, tablet, computer) to find out more. You are likely to find the information on the social media or website of the event you like, thereby determining the platform where you find the said information. Depending on the reach of that platform and their communication with you (registration information, day-calendars, invites to special events, finding out how many of your friends have also signed up), it will influence your attendance or non-attendance behaviour.

Rethinking digital

Does digital mean the opposite of physical? Dr Padmini Ray Murray, founder of the feminist design collective Design Beku, suggests looking at them not as opposites, but instead see how the two can co-exist. Going digital allows for the possibility of scale, for example for reaching masses. But it also allows for a different type of intimacy – cutting through distance and time. Concurrently, being digital doesn’t mean being networked; that one is connected to a large group just because one is online.Dr Murray suggests shifting the focus from economies of scale to economies of intensity – the former is a network that circulates information as a default, en masse, but the latter intensifies and circulates with care. Zoom boxes can be tiring, but they also offer the opportunity of intimacy in a way that is only otherwise possible by traditional travel across continents. It can allow for boutique experiences encompassing custom workshops and brainstorms, and allows for a different kind of imagination and flexibility.

The type of event and audience also brings to forefront the choice of platforms. Digital platforms are designed for varied reasons, which can be adapted as per the nature of the electronic event. For instance, as mentioned above, Zoom was designed as a meeting platform, which was adapted for “digital theatre”. A few others such as HopIn, Harkat Virtual Interactive stage and GatherTown, allow for newer experiments around, workshops and cultural conferences, and digital theatre.

In a post-pandemic world - or rather a mid-pandemic universe -, going digital requires both thought and capacity, the latter being scarce both in terms of funding and skill development in India’s cultural sector. This begets an approach that is collaborative and democratic – one replete with sharing, equitable access and translatability. If the pandemic has proven anything, it is the vulnerability of the cultural sector in the face of inadequate support structures and skill gaps in operating in the digital world. For cultural institutions sharing data, information and resources, as an act of collectivisation is an ideal way to confront the challenges of operating in the digital realm.