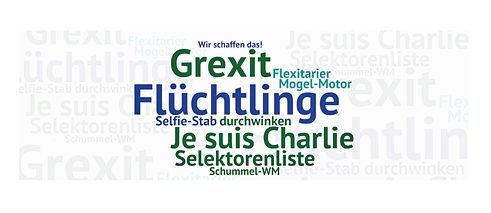

Tag Cloud from the ten words of the year 2015

| © GfdS

Can the state of a society be reflected in a word? Since 1997 a jury of the Association for the German Language (Gesellschaft für deutsche Sprache / GfdS) has been selecting the Word of the Year. Managing Director Andrea-Eva Ewels on a special kind of language retrospective.

Mrs. Ewels, how did the Association for the German Language get the idea to choose a Word of the Year?

Actually, the idea came to us. In 1972, in our members’ journal, the Mainz Anglicist Broder Carstensen, a member of the GfdS, published an essay on the 1971 Words of the Year. The article went down so well with our readers that we decided to select a list of Words of the Year every year. In 1977 this became a regularized activity.by the way, the choice of Words of the Year, by the way, has little to do with traditional linguistics. It’s a game – a “serious game” – as our former chairman Rudolf Hoberg called it in an interview.

As a matter of fact this game is now taken very seriously by the German public. The Words of the Year, a kind of annual linguistic looking back, are widely noticed and discussed. Would you say that they reflect the current state of German society?

Yes, I think so. Our archives can be read like a yearly chronicle. Anyone wanting to know twenty years from now what issues occupied people in Germany in 2015 has only to look at our Top 10.

Documenting language change

About the 2015 Word of the Year that’s certainly true.

You might well say that. Nothing preoccupies the German public so much as the issue of refugees. And it’s no wonder that we chose this word as Word of the Year. But another factor was also important, one that likewise plays a role in most decisions. Usually we choose a word that is also linguistically interesting. In

Flüchtling (i.e. refugees) we were particularly interested in the suffix

-ling. In German there are some similar words to which a negative meaning is attached – for example,

Eindringling (i.e. intruder),

Emporkömmling (i.e. upstart) and

Schreiberling (i.e. scribbler). Recently therefore there’s been a tendency to use instead of

Flüchtling the more neutral word

Geflüchtete (i.e. people fleeing). It’s unclear, however, whether this expression will prevail in general usage.

So you’re also interested in documenting language change?

Yes, definitely. The Words of the Year are specific examples of language change. Often they’re new creations such as

Wutbürger (i.e. enraged citizen), the 2010 Word of the Year. There are also words that are already known but have undergone an expansion of meaning.

Stresstest, the 2011 Word of the Year, actually comes from a medical context, but then became an integral part of everyday language and gained relevance in politics, economics and society as a whole.

-

© RioPatuca Images – Fotolia.com

© RioPatuca Images – Fotolia.com

“Flüchtlinge” (Refugees) – Word of the Year 2015

No other issue has so dominated the German public in 2015 as how to handle the numerous asylum seekers. But there was also another reason that the jury chose the word “Flüchtling” (i.e. refugee): the term is linguistically interesting. In a number of comparable word formations, such as “Eindringling” (i.e. intruder), the suffix “–ling”, which refers to a person characterized by a property or feature, tends to have a negative meaning. The term “Geflüchtete” (i.e. people who have fled) therefore may come to prevail instead.

-

© kleopatra14 – Fotolia.com

© kleopatra14 – Fotolia.com

“Lichtgrenze” (Light border) – Word of the Year 2014

The term refers to the light installation that commemorated the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Thousands of balloons, illuminated at night, marked the approximately 15 km course of the Wall through the formerly divided city. On the evening of 9 November 2014, the airworthy balloons attached to plastic rods were launched. The GfdS jury on “Lichtgrenze”: “The delicate transparency of the installation and the ascent of the balloons at the climax of the celebrations symbolized impressively the dissolution and abolition of the former demarcation line, which was dark in every sense”.

-

© bluedesign – Fotolia.com

© bluedesign – Fotolia.com

“GroKo” – Word of the Year 2013

“GroKo” is short for “grand coalition”. This is the term in Germany for a government alliance consisting of the two largest parties, the conservative CDU/CSU and the social democratic SPD. A grand coalition, such as came about after the federal election of 2013, is considered by many to be a stopgap solution, since the CDU/CSU and the SPD are traditional rivals. The neologism “GroKo”, with its echo of “Kroko”, a diminutive of the word for crocodile, gives expression to “a half-mocking attitude towards the coalition government”, as the jury put it.

-

© Calado – Fotolia.com

© Calado – Fotolia.com

“Rettungsroutine” (i.e. Rescue routine) – Word of the Year 2012

In 2012 the so-called “euro rescue” in connection with the aid payment to Greece was particularly widely discussed in Germany. The word “Rettungsroutine” reflects both the ongoing issue of Europe’s fragile economic situation and the numerous stabilization measures. “Linguistically interesting is the contradictory meaning of the two word-components: while ‘Rettung’ (rescue) in the strict sense means an acute but completed action, ‘Routine’ (routine) refers to a recurring development based on experience”, said the GfdS jury.

-

© Tom Bayer – Fotolia.com

© Tom Bayer – Fotolia.com

“Stresstest” (Stress test) – Word of the Year 2011

Originally, the term “stress test” was used in the field of human medicine to describe numerous physical and psychological tests of stress, and then gradually also came to be used in other contexts. In 2011 the expression was already so widespread that the jury came to the assessment that the term “is to be seen as a permanent part of everyday language”. Here the controversial construction of the new Stuttgart main station (Stuttgart 21), widely discussed by the public in 2011, is likely to have played an important role. The appraisal of this project by an external expert opinion was also called a “Stresstest”.

-

© Friedberg – Fotolia.com

© Friedberg – Fotolia.com

“Wutbürger” (Enraged citizen) – Word of the Year 2010

The neologism “Wutbürger” (i.e. enraged citizen) became known mainly through an eponymous essay that appeared in 2010 in the German news magazine “Der Spiegel”. The term describes the protest of people from a middle-class milieu against what they perceive to be arbitrary political decisions. “The word documents a great need on the part of citizens to have a say beyond the voting booth in socially and politically relevant projects”, said the statement of the GfdS jury.

-

© redaktion93 – Fotolia.com

© redaktion93 – Fotolia.com

“Abwrackprämie” (Scrappage premium) – Word of the Year 2009

In 2009 the so-called “environmental incentive” was introduced in Germany with the aim of aiding the domestic automotive industry, which had been hit by the 2007 financial crisis. Until September 2009 the buyer of a new car received under certain circumstances a premium of 2,500 euros for the scrapping of his old vehicle. The term “Abwrackprämie”, which previously had been used only in the shipping industry, swiftly became established in this context. Soon the private sector too was touting a “scrappage premium” – for furniture, washing machines and bicycles. This extension of the term’s range of use was decisive for the jury’s decision.

-

© Rawpixel.com – Fotolia.com

© Rawpixel.com – Fotolia.com

“Finanzkrise” (Financial crisis) – Word of the Year 2008

From today’s perspective it may be difficult to imagine that the word “financial crisis” has not always been a part of the standard vocabulary. But in fact the term has been used by the German public only since the beginning of 2008 – as a reaction to the momentous collapse of the American real estate market. The expression “Finanzkrise” (i.e. financial crisis) “summarizes the dramatic development in the banking, real estate and financial sectors and comprises the crisis in real estate, credit, liquidity and the market”, explained the GfdS in its decision.

-

© spuno – Fotolia.com

© spuno – Fotolia.com

“Klimakatastrophe” (Climate catastrophe) – Word of the Year 2007

In its decisions the jury of the GfdS focuses above all on words that stand for important social issues in the year. This relevance was particularly evident in the choice of the term “Klimakatastrophe” (i.e. climate catastrophe): “This expression succinctly indicates the perilous development that climate change has taken“. The word is composed of the noun “Klima” (i.e. climate) and “Katastrophe” (i.e. catastrophe), and in one stroke combines linguistically the decades of debate about the changing climate of the earth with the possible catastrophic consequences of this development.

-

© Ingo Bartussek – Fotolia.com

© Ingo Bartussek – Fotolia.com

“Fanmeile” (Fan park) – Word of the Year 2006

The expression was coined during the FIFA World Cup in Germany in 2006, when so-called FIFA fan festivals with public television broadcasting were set up at all venues. The original idea was that football fans who had no tickets should there be able to follow the games. But soon the fan festivals lost their surrogate character: at the “Fanmeilen” (i.e. fan parks) hundreds of thousands of football enthusiasts from around the world came together for a shared “public viewing”.

-

© Bundesregierung/Guido Bergmann

© Bundesregierung/Guido Bergmann

“Bundeskanzlerin” (Lady Chancellor) – Word of the Year 2005

At the end of November 2005, Angela Merkel was elected the first “Bundeskanzlerin” (i.e. “chancellor” with the feminine grammatical ending). Today we make a point of specifying the feminine suffix -in in descriptions of jobs and personal designations. In 2005 the GfdS looked upon the feminine form of the word “Bundeskanzler” as an important sign of this linguistic change. “A few decades ago a woman at the head of the government would have been called the ‘Bundeskanzler’”, explained the jury in its statement.

Pithiness instead of frequency

Speaking of language change, must the Words of the Year always be single words? In Great Britain, the editors of the 2015 “Oxford Dictionaries” chose a pictograph, an emoji of a face with tears of joy, as Word of the Year.

We still choose words in the traditional sense as Words of the Year. It’s only in tenth place in the list that you sometimes find a noun phrase or a sentence. But I think the idea of choosing an emoji as Word of the Year is as witty as it is creative.

In addition to linguistic peculiarities, is the frequency of mention a main criterion of selecting the Word of the Year?

It’s not the frequency of an expression that’s important but its pithiness. This is especially evident when the word has a high semantic content. The term

Flüchtlinge, for example, stands for the entire refugee problem. The issue dominates not only politics but also the whole of society. It has found its way into almost every area.

Exactly this approach has brought you a lot of criticism. Can you understand that?

As a matter of fact there’s much discussion every year about the Word of the Year. We receive many letters from people who don’t agree with the choice because they don’t know the particular word or would have chosen another. Sometimes the chosen Word of the Year is perceived as boring because it’s almost too obvious, as for instance in 2010 the word

Abwrackprämie (i.e. scrappage allowance). Or the word is too little known and therefore criticized, as for instance in 2010 the word

Wutbürger. This word is now firmly established in everyday language. The linguistic development and subsequent degree of recognition of a particular word can’t be predicted – neither by the jury nor by the wider public.

Worst Word of the Year

It’s important for you not to give evaluations or recommendation with the selection. That’s different with the so-called Worst Word of the Year (in 2015 it was „Gutmensch“, (i.e., do-gooder), which since 1991 has been made known parallel to the Word of the Year and was also originally an idea of the GfdS. How do the two concepts differ?

The Worst Word of the Year is about objectively inappropriate or inhuman formulations in public parlance. The Word of the Year is not primarily about inappropriate formulations, but rather about words that make history, are linguistically interesting and are quite capable of exercising criticism.

Are Words of the Year also chosen in other countries?

There’s long been a number of imitators that afford a view of the social and political issues that were current in other countries in a particular year. Austria has been choosing its own Word of the Year since 1999; in 2015 it was

Willkommenskultur (i.e. welcoming culture). Switzerland introduced its own voting for the Word of the Year in 2003. In 2015 the victor was

Überarztung (i.e. over-doctoring). And the United States has had a Word of the Year since 1991.

Dr. Andrea-Eva Ewels, Managing Director of the Association for the German Language (GfdS)

| © GfdS

Andrea-Eva Ewels has been Managing Director of the Association for the German Language (GfdS), an association for the fostering and study of the German language, since 2010. Previously, she was a research associate in Linguistics at the University of Mainz and worked as a journalist.

Dr. Andrea-Eva Ewels, Managing Director of the Association for the German Language (GfdS)

| © GfdS

Andrea-Eva Ewels has been Managing Director of the Association for the German Language (GfdS), an association for the fostering and study of the German language, since 2010. Previously, she was a research associate in Linguistics at the University of Mainz and worked as a journalist.

Discuss this with us

What is your personal “Word of the Year”? Share it with us via the comments function.

Dr. Andrea-Eva Ewels, Managing Director of the Association for the German Language (GfdS)

| © GfdS

Andrea-Eva Ewels has been Managing Director of the Association for the German Language (GfdS), an association for the fostering and study of the German language, since 2010. Previously, she was a research associate in Linguistics at the University of Mainz and worked as a journalist.

Dr. Andrea-Eva Ewels, Managing Director of the Association for the German Language (GfdS)

| © GfdS

Andrea-Eva Ewels has been Managing Director of the Association for the German Language (GfdS), an association for the fostering and study of the German language, since 2010. Previously, she was a research associate in Linguistics at the University of Mainz and worked as a journalist.