Indigenous Rap

“We don’t fit labels”

Young rappers of indigenous origins are entering the Brazilian music scene and creating a legion of fans. As they strive to defend the rescue of their own origins and denounce the violence in their communities, they also face prejudice and hate on social networks. “Music is to question the state of things.”

By Ana Paula Orlandi

Retomada (Reclamation) is the title of the album to be released this year by the MC Bros, a rap group formed by two duos of brothers of the Guarani-Kaiowá peoples. CH and Kelvin Mbarete live in the Bororó village, and Bruno Veron and Clemerson Batista live in the neighboring village, Jaguapiru. With around 16 thousand people, the communities are located on the Dourados Indigenous Reserve, created in 1917 in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, one of the centers of agribusiness in Brazil. “We want to denounce the reality of violence that our community experiences. One of the songs we sing is called Terra Vermelha (Red Earth), inspired by the story that the land here is red because there were many indigenous peoples who shed their blood in Mato Grosso do Sul,” says Veron. “We are fighting for the right to exist,” he adds.

The record title, which is also one of the names of the songs composed by the group, refers to the movement to reclaim ancestral lands which indigenous leaders in Mato Grosso do Sul started in the 1970s. There, from the end of the 19th century onwards, the government started handing over original territories to non-indigenous people, such as farmers. And to this day, the land remains a subject of dispute: Mato Grosso do Sul is the state where the most indigenous people were killed in Brazil between 2003 and 2019, according to a study by the Socio-Environmental Institute, a civil society organization based in São Paulo, that works alongside indigenous and quilombo communities in Brazil. Among the victims is the grandfather of Bruno Veron and Clemerson Batista, the indigenous leader Marcos Veron, who was murdered in 2003 over the land issue.

Prejudice on All Sides

13 years into their career, the MC Bros define themselves as “Brazil’s first indigenous rap group” and write, mainly, rhymes in Portuguese and Guarani, for instance the song Eju Orendive, which has more than 480,000 views on YouTube. In addition to their new album (the quartet’s first) CH, Kelvin, Bruno and Clemerson participated in the first evening dedicated to rap in September at Rock in Rio, the biggest Brazilian music festival. They shared the stage with Xamã, a rapper of indigenous descent, born and raised in Rio de Janeiro, who reached the top of the Spotify Brazil ranking in 2021.This acceptance, however, was not easy. Resistance to rap made by indigenous people comes from several sides, Bruno Veron points out: “When the MC Bros came on the scene, we faced a lot of prejudice. And this was both within our indigenous community as well as on the Brazilian hip hop scene. It took a while for us to be respected,” the rapper says. “But rap has no borders. Its essence is the same everywhere. Rap is denunciation, it’s activism, it’s music to question the state of things.”

Confronting Misogyny

Today, the Brazilian hip hop scene is home to other names of indigenous artists, like for example MC Anarandá, also from the Guarani-Kaiowá ethnic group. Still without a record, last year the rapper released the video of the single Feminicídio (Feminicide), in which her verses recall the death of a friend: “Enough torture of the perforated body. Enough women with bloodied faces. Enough of women living in humiliation. Enough of women getting their hearts ripped out.” Rapper MC Anarandá

| Photo: Edgard Kanayko

Anarandá’s songs mix Portuguese and Guarani to address issues related to indigenous women. “Misogyny is present everywhere, including in the villages. Men think all we can do is take care of our children and do housework, but we were born to be free, to do what we want,” defends the rapper, who promotes her work on the internet. “I am an independent artist and I take care of everything myself, but you have to prepare yourself psychologically to be on social media, which are full of racist, prejudiced comments from haters. There is a lot of hate towards indigenous people in our country. There are people who think we have no place at universities, on social networks or stages. Or that we cannot sing rap because it has nothing to do with our culture,” she observes.

Rapper MC Anarandá

| Photo: Edgard Kanayko

Anarandá’s songs mix Portuguese and Guarani to address issues related to indigenous women. “Misogyny is present everywhere, including in the villages. Men think all we can do is take care of our children and do housework, but we were born to be free, to do what we want,” defends the rapper, who promotes her work on the internet. “I am an independent artist and I take care of everything myself, but you have to prepare yourself psychologically to be on social media, which are full of racist, prejudiced comments from haters. There is a lot of hate towards indigenous people in our country. There are people who think we have no place at universities, on social networks or stages. Or that we cannot sing rap because it has nothing to do with our culture,” she observes.

Pride in Language

At 25 years old, Anarandá is mother of a five-year-old boy and is raising two teenage nieces in the village of Guapoy, in the municipality of Amambai in Mato Grosso do Sul. To sustain her family, she works as a Guarani teacher, talks about cultural diversity in schools in the region and promotes local shops on her social networks. Anarandá also participates in the Voa parente project, from the Azuruhu music label, created with the aim of promoting works by artists of different ethnicities and musical styles. Nativos MCs from Mato Grosso

| Photo: Claudio Reis

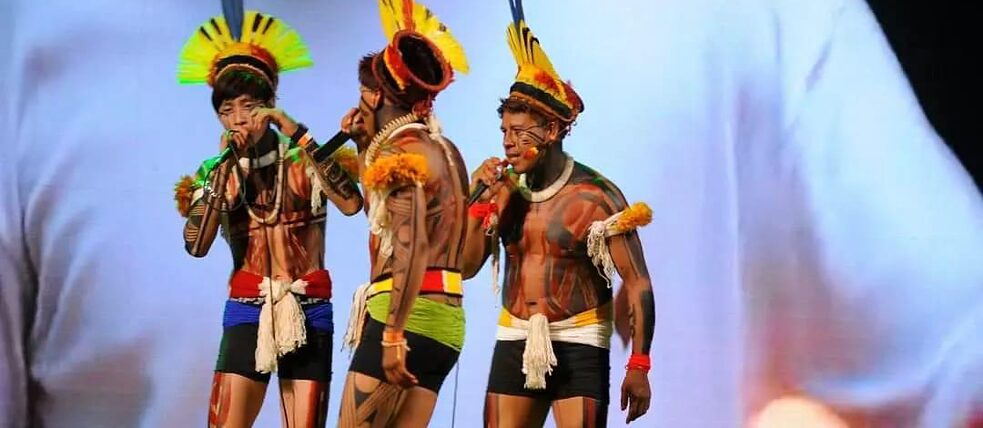

The first fruit the project reaped was released last January: the video Tente entender (Try to Understand) by the Native MCs. Formed in 2021, the rap group includes Macc JB, Urysse Kuykuro and Pajé MC – the three belong to the Kuikuro ethnic group and live in the Afukuri village in Alto Xingu in the state of Mato Grosso. “Our rhymes are expressions of pride in our language. Indigenous languages are alive, although many non-indigenous people believe they have died. Rap is a way of showing this vitality,” says Urysse Kuykuro. “In our shows, we wear necklaces, headdresses, armbands, and urucum in our hair. Our body is political, and it also conveys a message of struggle and permanence,” she adds.

Nativos MCs from Mato Grosso

| Photo: Claudio Reis

The first fruit the project reaped was released last January: the video Tente entender (Try to Understand) by the Native MCs. Formed in 2021, the rap group includes Macc JB, Urysse Kuykuro and Pajé MC – the three belong to the Kuikuro ethnic group and live in the Afukuri village in Alto Xingu in the state of Mato Grosso. “Our rhymes are expressions of pride in our language. Indigenous languages are alive, although many non-indigenous people believe they have died. Rap is a way of showing this vitality,” says Urysse Kuykuro. “In our shows, we wear necklaces, headdresses, armbands, and urucum in our hair. Our body is political, and it also conveys a message of struggle and permanence,” she adds.

Reconnecting with Origins

Rescuing indigenous ancestry is also the central theme of Ritual (Ritual), the first record by rapper Souto MC, who was born 27 years ago on São Paulo’s periphery, where she still lives today. Released in 2019, the album opens with a poem written by the artist and read by her father, Pedro Neto, from Ceará now based in São Paulo’s capital and a descendant of the Kariri ethnic group from the Brazilian Northeast. Next comes the track Caça e caçadora (Hunting and the Hunter) the lyrics of which evoke the search for one’s own identity.For the rapper, Ritual is a collective album. “It’s an album that talks about my very intimate process of reconnecting with my origins, but also seeks to talk to other people who are going through the same experience. At home we always talk about the indigenous roots of our family, but in a superficial way. Over the last four years, I decided to dive into that history to understand my place in it,” says Souto, whose ten-year career has mostly been dedicated exclusively to rap. In 2015, she also started composing sambas, such as Altamira, a track in Ritual. “Indigenous people are on the outskirts of large cities not only in Brazil, but throughout the world. Here, people listen to samba, rap, funk, and it ends up influencing our sound. We don’t fit labels,” she concludes.