With stars like Gentleman, internationally renowned sound systems like Pow Pow and world-famous festivals like Summerjam, reggae has long since become a matter of course in Germany. In the space of only three decades, a reggae culture modelled on the Jamaican paradigm has established itself here in Germany – though producing a great many variants of and distinct approaches to reggae.

Welcomed by hippies as laid-back music from the “Third World”, romanticized by punks as rebel music, and celebrated by Schlager fans as Caribbean exoticism, reggae in Germany caught on between these three poles in the late 1970s.

1980s activists

Before that, there were no visible manifestations of a home-grown German reggae culture: no reggae artists, producers, sound systems (i.e. mobile deejay crews with their own equipment), no record shops and hardly any journalists who were really in the know. And how could it have been any other way? After all, it wasn’t Caribbean immigrants, but middle-class white kids who co-opted reggae, as relayed by the media and record albums, mostly to construct a countercultural identity for themselves. But those who played reggae – whether actively as musicians or passively on records – could do so only as fans on the fringes of a movement that was happening abroad.

Fortunately, there were some journalists and musicians who wanted to find out for themselves and travelled to Jamaica or England to gain insight into reggae culture. Thanks in large part to these activists, a fledgling reggae culture eventually sprouted in Germany over the course of the 1980s, with bands like The Vision (Hannover), Herbman Band (Varel) and Dub Invaders (Munich), deejays like Natty U (Dortmund) and the Bavarian rebel Hans Söllner (Bad Reichenhall), sound systems like Conquering Sound (Hannover), festivals like Summerjam (Cologne), and the first reggae record shops and labels like Irie Records (Münster) and Fotofon (Aachen).

Generation Gentleman

© Pow Pow Movement

© Pow Pow Movement

But reggae didn’t really make it big in Germany until the 1990s with the second generation of activists and listeners, who became fans via digital dancehall, hip hop and jungle. The codes and rituals, techniques and styles of reggae culture first had to be learned, tested and laboriously culturally configured. Sound systems like Pow Pow (Cologne) and Silly Walks (Hamburg) pioneered those developments and gave Gentleman (Tilmann Otto) from Cologne his first shot at the microphone.

Besides his musical talent and perseverance, Gentleman owed his first regional, then nationwide and ultimately international success chiefly to his striving for authenticity. From the outset, his goal was not just to copy the “original style” from Jamaica, but to internalize it. His street cred is grounded in his perfect mastery of the symbolic codes of reggae culture, which he picked up while living in Jamaica for many years.

Most of Gentleman’s cohorts shared his unconditional identification with Jamaican musical culture, which ultimately became the model for large swathes of the German reggae scene. Artists as diverse as Dr. Ring-Ding, Martin Jondo, Jahcoustix and Cornadoor, sound systems like Soundquake, Supersonic and Sentinel, producers like Ingo Rheinbay (Pow Pow) and Pionear (Germaican Records) still swear by “original style” reggae between roots and dancehall.

Vast array

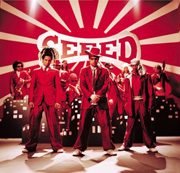

© Warner Music

© Warner Music

But progressive reggae men have also been making their voices heard since the late 1990s. The Afro-German artist Patrice initially cultivated a free-spirited singer-songwriter style, expanding the stylistic ambit of reggae, over the course of his career, to include elements of pop, African rhythms and soul. Meanwhile, beyond the reggae scene, Rhythm & Sound from Berlin were internationally acclaimed for their innovative brand of reggae groove that involved a synthesis of dub and techno. The 11-member dancehall combo Seeed achieved similar recognition, evolving in the space of only five years into the world’s most impressive live band at the interface between dancehall, reggae, pop and hip hop. Like Patrice, Seeed are no longer striving to get reggae culture established in Germany – it already is. And its popularity is due in no small measure to the magazine

Riddim as well.

Seeed, and for a while Jan Delay and D-Flame, too, won over a new generation of listeners at the turn of the millennium with their distinctive admixture of German lyrics, humour and a fat sound. Above all, singing and toasting reggae in German dispensed with the quandary of trying to comprehend lyrics in the

patois spoken by Jamaicans (alongside the official national language: English): a creole mix of African dialects peppered with Portuguese, Spanish and English expressions. And using German brought out the subject-matter of the songs more clearly. Following in the footsteps of Seeed and Jan Delay, artists like Nosliw, Mono & Nikitaman, Maxim (all on Rootdown Records), Ganjaman and Ronny Trettmann now reflect for the most part German realities and countercultural lifestyles and attitudes in their lyrics. They are, in a word, gravitating towards the subject-matter of “ordinary” pop songs, though without neglecting reggae’s particular musical code. Reggae has spread in every direction in present-day Germany.