Zero Hour in Film

Rubble, Utopia, New Beginnings

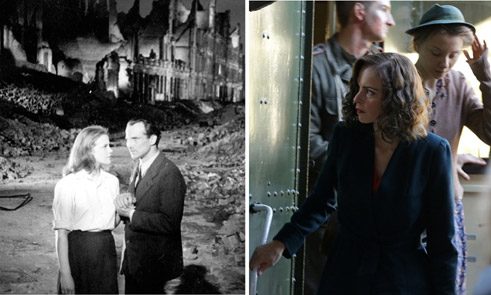

From “The Murderers Are Among Us” to “Phoenix” – the period immediately after the Second World War has also been dealt with time and again in cinema, such films always reflecting the way in which Germans view themselves.

The former German Empire was in tatters when the Second World War came to an end in 1945 – not only literally but also in terms of morale. Cinema was one of the functions and institutions that had been thoroughly discredited by National Socialism. It had faithfully served the Hitler regime as a propaganda tool, so by the time the era ended there were very few filmmakers who still had a clean record, that is to say who were regarded as politically and artistically “untainted”. So what form should new German cinema take? It certainly got off to a promising start.

The first German post-war film was a “Trümmerfilm”

The first German post-war film, with its telling title of The Murderers Are Among Us, was a major cinematic event when it premiered on 16 October 1946. In the bombed-out city of Berlin, two people find themselves forced to share a flat – one is a woman who has survived life in a concentration camp, the other a soldier recently returned from the front. Their roles became representative of many films about “returnees”: the pragmatic woman gets to work clearing up, while the man – traumatized by his wartime experiences – remains paralysed by cynicism and lethargy. At the end, however, he brings his former superior officer, a war criminal, to justice. Wolfgang Staudte, a director who had managed to get through the Nazi period with his record untarnished, made this film – a dark and expressionistic shadow play – under the supervision of the Soviet occupation authorities at the newly-founded DEFA.The clear appeal to address and punish Nazi crimes was an exception in the short-lived “Trümmerfilm”– literally, “rubble film” – genre. Although realistically depicting existential fears and hardship, they also offered hope and provided a visual indication of a new direction: really quite successful films such as Somewhere in Berlin (Gerhard Lamprecht, 1946) and Love ‘47 (Wolfgang Liebeneiner, 1949) made a visually aesthetic process of renewal seem possible, a non-sugar-coated depiction of reality in the spirit of Italian neorealism. The rapid economic upswing soon put paid to such approaches, at least in the West. Ultimately, the wider public was no more interested in realism than it was in the question of guilt – there was no room for either in the optimistic idealized cinema visions of the 1950s, the most successful epoch of West German post-war film.

Zero hour: a missed opportunity ...

Without this period of artistic suppression, it is impossible to understand the political wake-up call of New German Cinema, when directors like Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Volker Schlöndorff and Werner Herzog launched their attack on German self-perception post-1968. Fassbinder even went a step further with The Marriage of Maria Braun (1978), one of his most successful films. The tale of the supposed war widow Maria Braun, who takes part in the economic miracle with unscrupulous charm and sheer assertiveness, is the story of the young Federal Republic of Germany – and one of a missed opportunity. A year earlier, Edgar Reitz’s Zero Hour (1977) had already depicted the end of the war as offering a kind of utopian freedom: between the retreat of the US Army and the advance of the Soviets, a disused railway station near Leipzig becomes a blind spot in history in which a colourful and motley bunch of individualists is enjoying life. There is no government, and just for a while anything seems possible. Fassbinder also describes this vacuum in which a young woman takes control of her own life. She fails, however, as the male order is restored behind her back.... or a test that has been successfully overcome

The critical thrust of New German Cinema was not destined to last long, either. In the 1991 film Rama dama (the Bavarian title, roughly translated, means “let’s clear up”), Joseph Vilsmaier presents women of Munich clearing away the rubble to a soundtrack of upbeat swing music. Nylons and lipstick are finally back, not to mention flirting with the American occupying forces – nostalgia is the order of the day in the “modern Heimatfilm” (a Heimatfilm is traditionally a sentimental depiction of homeland). Zero hour becomes a test that has been successfully overcome, a fondly remembered part of one’s own life’s achievements. In any case, the myth of the doughty “rubble woman” has long become part of Germany’s collective visual memory. Yet Vilsmaier’s approach to depicting history, which had little political content but was visually pleasing, quickly became the artistic standard when it came to examining German history, and one that was also suitable for more challenging subject matter such as the rape of German women by Russian soldiers after the end of the war in A Woman in Berlin (2008). This allowed TV films depicting events in a modern style such as Tannbach (Alexander Dierbach, 2015) – about a village on the inner German border that was divided in 1945 – to tackle formerly awkward questions of guilt and continuity without being provocative. Indeed, zero hour does now offer freedom – to tell fascinating stories.Is nostalgia all that remains?

“Phoenix” (Trailer) | © Piffl Medien via youtube.com

In his film Phoenix (2014), author filmmaker Christian Petzold recently supplied a counterpoint to this image of a successful critical engagement with history. Petzold, well-versed in film history, styles his heroine Nelly Lenz much like the two major female stars of zero-hour film: the imperturbable Hildegard Knef in The Murderers Are Among Us and the glamourous Hanna Schygulla in The Marriage of Maria Braun. At the beginning, however, Nina Hoss who plays Nelly is a Jew who has escaped from the hell of Auschwitz, emaciated and facially disfigured – the kind of genuine concentration camp survivor that Knef was not yet allowed to portray. Her uncanny transformation is on the one hand a cinematic puzzle with references to Alfred Hitchcock, Ingmar Bergman and François Truffaut, and on the other a serious engagement with the real horror of the Holocaust and the suppression mechanisms employed by German post-war society. It would appear that zero hour continues to concern the Germans and is a narrative that is far from complete.