Brutalist Architecture

Back to concrete!

Grey, rough, inhuman: Brutalist architecture has a bad reputation. But that is currently changing. Fact is that the concrete monsters that arose from the 1950’s through the 1970’s can also be seen and described in other ways: as distinctive monumental sculptures – engrossing, immediate and bold.

“Nothing about these buildings is fake. They display their material, whether concrete, brick or steel, purely and openly. Nothing has a hollow ring to it, like these insulation facades these days. Nothing is cladded, refined or smoothed away. This architecture stands right in the rough-and-tumble of life,” says Oliver Elser, a fan of Brutalism and curator at the German Museum of Architecture (Deutsches Architekturmuseum) in Frankfurt am Main.

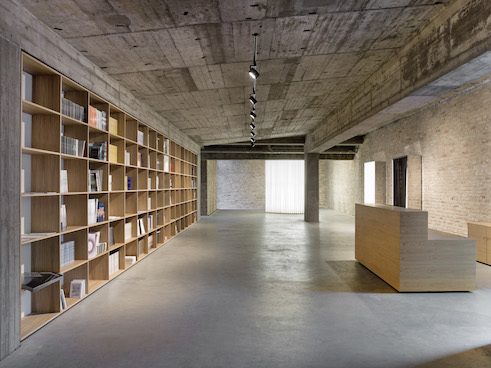

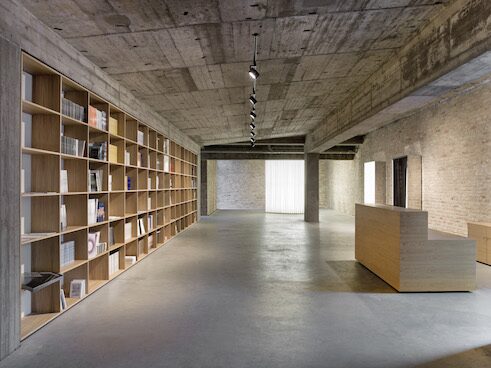

St. Trinitatis in Leipzig | Academy of Architecture and Building

| Photo: Uwe Pilz

Originating in the United Kingdom and starting in the 1950’s, Brutalist buildings arose as a reaction to the endless sameness of glass fronts and smooth, grid-like facades of post-war architecture. Brutalism is more of an attitude than a style, according to Oliver Elser. An attitude that made the raw building material (béton brut) into a design element. Butted edges, grain and knotholes of the wooden shuttering into which the concrete was poured are left un-plastered and therefore visible.

St. Trinitatis in Leipzig | Academy of Architecture and Building

| Photo: Uwe Pilz

Originating in the United Kingdom and starting in the 1950’s, Brutalist buildings arose as a reaction to the endless sameness of glass fronts and smooth, grid-like facades of post-war architecture. Brutalism is more of an attitude than a style, according to Oliver Elser. An attitude that made the raw building material (béton brut) into a design element. Butted edges, grain and knotholes of the wooden shuttering into which the concrete was poured are left un-plastered and therefore visible.

Spectacular houses of worship

A conspicuous number of church buildings are Brutalist. Gottfried Böhm’s Mariendom in Neviges, a small place in North Rine-Westphalia for instance, a spectacular concrete folded-plate structure reminiscent of tents clustered together that provides space for 6000 people. Or the block-like Church of St. Agnes by Werner Düttmann in Berlin that now serves as a gallery. The concrete dome of the Don Bosco Church by Thomas Wechs in Augsburg counts among them, just as the former priory Church of the Holy Trinity in Leipzig erected by the GDR’s Academy of Architecture and Building. Mariendom in Neviges | Gottfried Böhm

| Photo: Seier+Seier

In addition to houses of worship, primarily public buildings such as city halls, cultural centres or schools were erected, in large-scale format and with bold, Brutalist verve. The backdrop was a political aesthetic. Buildings for ordinary citizens were to be at least as monumental as the castles of the powerful of old.

Mariendom in Neviges | Gottfried Böhm

| Photo: Seier+Seier

In addition to houses of worship, primarily public buildings such as city halls, cultural centres or schools were erected, in large-scale format and with bold, Brutalist verve. The backdrop was a political aesthetic. Buildings for ordinary citizens were to be at least as monumental as the castles of the powerful of old.

Monumental learning factory

The Ruhr University Bochum arose thus, as the beacon of a democratic educational offensive, from 1963 until 1970. Architect Helmut Hentrich designed the university as a “harbour in the ocean of knowledge”: 13 high-rises of steel-reinforced concrete, each nine storeys high and about 100 metres long, symbolise ocean liners at berth in this harbour. Beneath them extends a kilometre-long underground garage system. Stairways and covered passages open up and connect widespread mezzanine levels. Not all of the 41,000 students feel comfortable at their university, and the daily newspaper Die Welt even went so far as to describe the complex as “a learning factory of truly phenomenal hideousness.” Ruhr University Bochum | Helmut Hentrich

| Photo: © RUB, Marquard

Tenants, too, are not consistently enthusiastic about the kind of concrete architecture erected by, for example, Gottfried Böhm from 1969 until 1974 in Cologne-Chorweiler. Too inflexible, too little consideration of the wished of the residents, runs the criticism.

Ruhr University Bochum | Helmut Hentrich

| Photo: © RUB, Marquard

Tenants, too, are not consistently enthusiastic about the kind of concrete architecture erected by, for example, Gottfried Böhm from 1969 until 1974 in Cologne-Chorweiler. Too inflexible, too little consideration of the wished of the residents, runs the criticism.

Waves of rediscovery

Doubtlessly, the colossi in grey provide imposing photo motifs. But how well can one in fact live, learn and work in Brutalist buildings? “Very well, finds Brutalism expert Oliver Elser, citing as examples London’s Barbican Centre and Munich’s Olympic Village, now very much in demand. “Brutalist architecture’s quality - drastic, in-your-face – is currently being rediscovered.” And not just in social media, photo volumes or architectural congresses – increasing numbers of owners and users of Brutalist buildings have come to appreciate their recalcitrance and unwieldiness. This reassessment dovetails with the “wave of rediscovery“ characteristic of the history of building and architecture. Oliver Elser: “The Wilhelminian buildings spurned from 1920 until 1970 are now in high demand, for example.” Residential buildings in Chorweiler | Gottfried Böhm

| Photo: Elke Wetzig

Closely connected with Brutalism’s comeback is a new take on its most important construction material. While in the 1960’s concrete still stood for utopia and new horizons, it is now mainly equated with social problems in satellite towns Oliver Elser is convinced: “Nonetheless, concrete’s grotty image is changing,“ After all, the building material itself is not responsible for urban-planning and policy blunders. But this insight is too late for many Brutalist buildings: they have been torn down in the meantime.

Residential buildings in Chorweiler | Gottfried Böhm

| Photo: Elke Wetzig

Closely connected with Brutalism’s comeback is a new take on its most important construction material. While in the 1960’s concrete still stood for utopia and new horizons, it is now mainly equated with social problems in satellite towns Oliver Elser is convinced: “Nonetheless, concrete’s grotty image is changing,“ After all, the building material itself is not responsible for urban-planning and policy blunders. But this insight is too late for many Brutalist buildings: they have been torn down in the meantime. Olympic village in Munich | Heinle Wischer und Partner

| Photo: Bernhard Betancourt

To rescue endangered buildings and to document the robust outlandishness of this architecture, the German Museum of Architecture, the Wüstenrot Foundation and Uncube Magazine have launched the initiative #SOSBrutalism. Centrepiece is a continually growing online archive currently with about 1000 buildings around the world, classified among other things according to their degree of endangerment.

Olympic village in Munich | Heinle Wischer und Partner

| Photo: Bernhard Betancourt

To rescue endangered buildings and to document the robust outlandishness of this architecture, the German Museum of Architecture, the Wüstenrot Foundation and Uncube Magazine have launched the initiative #SOSBrutalism. Centrepiece is a continually growing online archive currently with about 1000 buildings around the world, classified among other things according to their degree of endangerment.  St. Agnes in Berlin | Werner Düttmann

| Photo: KÖNIG GALERIE Berlin | Roman März

And the decades do not pass without leaving their traces on Brutalist buildings. They require expert repair and renovation. A case in point: coatings from bridge and waterway construction are being tested on the landmarked Mariendom in Neviges. And the incremental renovation of Ruhr University is being accompanied by functional improvements. Curator Oliver Elser is not always in agreement with this, but he basically finds that: “Brutalist architecture doesn’t belong under a bell jar. You have to continue building on it.“

St. Agnes in Berlin | Werner Düttmann

| Photo: KÖNIG GALERIE Berlin | Roman März

And the decades do not pass without leaving their traces on Brutalist buildings. They require expert repair and renovation. A case in point: coatings from bridge and waterway construction are being tested on the landmarked Mariendom in Neviges. And the incremental renovation of Ruhr University is being accompanied by functional improvements. Curator Oliver Elser is not always in agreement with this, but he basically finds that: “Brutalist architecture doesn’t belong under a bell jar. You have to continue building on it.“