Digital Fundamental Rights

“In political terms the discussion is necessary”

Do our fundamental rights protect people in the digital age? Digital experts from Germany have tried to find an answer – with the Charter of Fundamental Digital Rights of the European Union. An interview with co-initiator Wolfgang Kleinwächter.

Mr. Kleinwächter, why do we need digital fundamental rights?

The world in which we live has changed. In the digital age, much of what we have considered safe has been put into question. We must therefore ascertain to what extent fundamental rights are also valid in the digital age and where there is a need for an expanded interpretation.

So the question is whether the fundamental rights of the EU protect us in times of big data, social networks and algorithms against surveillance and censor? Critics of the Digital Charter say “Yes, they do, they need only be applied accordingly”.

The existing fundamental rights protect freedom of the individual from the encroachments of public authority. That’s good, but it’s not enough. In an age of unbounded, technically supported and economically marketable communication we are just beginning to realize that national state is not omnipotent and cannot alone comprehensively guarantee our freedoms. Private companies like Facebook manage many components of communication. This affects individual rights such as freedom of expression and data protection. The draft of the Digital Charter therefore goes beyond existing rights: we want to obligate private companies to take appropriate action when it comes to protecting fundamental rights.

Pause and examine

But Facebook and company have long since created their own game rules.Our society is organized in national states with their own jurisdictions. Cyberspace knows no national boundaries. This makes the situation complicated and generates tensions that only the close cooperation of the makers of “code” on the one hand and “law” on the other can relax. In recent years there has been a consensus that the internet should not be “strangulated” by strict regulation. A bureaucratic monster of censorship and regulations would stifle innovation and the benefits of the information society. But we also can’t leave developments in the hands of the companies and technicians.

Rules and laws applying to digital life are now being openly discussed. Why the change?

The effects of the information revolution are only now becoming slowly visible. Everything, from business models to private communication, is being put to the test. This also applies to our social rules. The change resembles reactions to the Industrial Revolution. At first there wasn’t any social legislation; this came only after the negative consequences of capitalism became visible. Thanks to the internet we can do things that were impossible twenty years ago. But all freedoms can be misused. Cybercrime is just one example. Here you have to pause and examine whether the existing legal situation and its instruments are sufficient or whether they have to supplemented and expanded.

The Digital Charter pertains not only to current questions, but also to the future of work and artificial intelligence. The impact these technologies will have on our daily lives is still unclear. Is the Digital Charter trying to regulate something that doesn’t yet even exist?

We should try to avoid the retrospective reproach of having marched into a catastrophe with open eyes. Could artificial intelligence in the end turn against human beings? To give a legal answer to this question is too early. But in political terms the discussion is necessary. Especially when it comes to the internet of things or artificial intelligence, there is a similarity to the development of nuclear energy. On the one hand, nuclear technology has made possible positive new developments; at the same time, it has brought with it the threat of atomic war. A lively debate on these subjects is necessary so as to discover the border lines.

Lessons from the past

You cite the Industrial Revolution and the invention of nuclear energy; what can we learn from the upheavals of the past for this debate?Don’t be afraid, but don’t be reckless. We have to create a broad alliance, encompassing all stakeholders and participants. Not only the government, but also the private sector, civil society and the technological and academic communities.

The charter is called the Charter of Digital Fundamental Rights of the European Union, but the people who worked on it were exclusively members of the German digital elites.

Self-doubt has plagued the members of the group from the first day, but somebody has to get the ball rolling. If the charter is to have an effect, however, the debate must go beyond the elite circle of self-engaged activists.

With the aim of creating a common European legal framework?

Actually, that wouldn’t be sufficient. The internet is a global phenomenon and we have to find global solutions. But if Europeans can sustainedly be heard in the global concert, they could play a very significant part in shaping global regulations. This process, however, will take several years before it yields concrete results.

How far along is the debate about digital fundamental rights in other countries?

These discussions have been going on since at least the UN World Summit on the Information Society in 2003. A step forward took place in 2014 when the Universal Declaration on Basic Principles of Internet Governance was adopted at the NetMundial conference in Sao Paulo. It sets human rights as the foundation for all global internet policy. The German initiative is a further contribution; we have, so to say, poured more water into a steadily flowing river. To date, this debate hasn’t been conducted in Germany with the seriousness and at the high political level that is actually called for. Our chief motive was to kick off this discussion. Digital fundamental rights are not only for technical experts. They are for everyone. And they belong in major policy decisions just like cyber security and the digital economy.

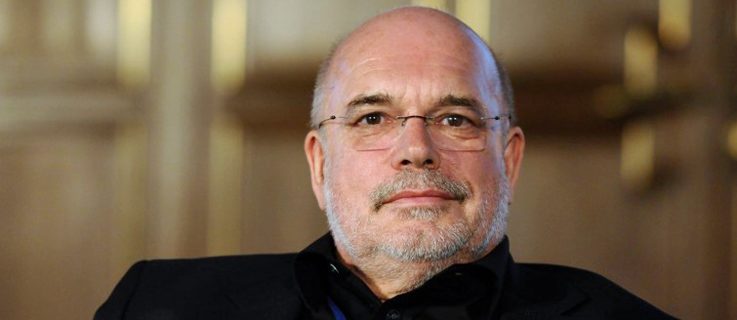

For more digital rights: the internet governance expert Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Kleinwächter

| Photo (detail): © Private

Wolfgang Kleinwächter is one of the initiators of the Charter of Digital Fundamental Rights of the European Union. Since 1998 he has been Professor of Internet Policy and Regulation at the University of Aarhus. He was a member of the board at ICANN and is currently a member of the Global Commission on Stability in Cyberspace (GCSC).

For more digital rights: the internet governance expert Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Kleinwächter

| Photo (detail): © Private

Wolfgang Kleinwächter is one of the initiators of the Charter of Digital Fundamental Rights of the European Union. Since 1998 he has been Professor of Internet Policy and Regulation at the University of Aarhus. He was a member of the board at ICANN and is currently a member of the Global Commission on Stability in Cyberspace (GCSC).

The Digital Charter (Charter of Digital Fundamental Rights of the European Union) was initiated by prominent Net activists, politicians, scientists and journalists on 30 November 2016. Its so far 23 articles (as of June 2017) call for legally binding fundamental rights in the digital world at the European level. In December 2016 the Digital Charter was presented to the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs of the European Parliament.

Comments

Comment