Cyber defence

Teutates fights Twitter viruses

Cyberwar sounds like an action film but the reality is much more prosaic. Guarding against cyberattacks is mostly a matter of vigilance. In Germany, a special agency is tasked with protecting politicians, businesses and private individuals from the perils of life online.

By Wolfgang Mulke

The gods of the past would rub their eyes in amazement today. Could Teutates, for example, who led the ancient Celts in war and peace, provide divine protection against the dangers lurking in social networks? Confronted with the large monitors on the wall of the national IT Situation Centre, he would probably see no more risks for his people than a normal mortal.

The computer software named after him creates screen graphics that visualise current activity on the short message service Twitter. Christian Eibl, who heads the Situation Centre, leads a team of anomaly-spotters. A surging new hashtag that might be connected with IT security problems, for example, makes the Situation Centre staff prick up their ears. They investigate to make sure it is not a cover for a new virus, cyberattack or unidentified malicious software. Such are today's weapons of war. A far cry from the analogue warfare waged between Romans and Gauls, malware and botnets land blows once delivered by swords and fists.

Large screens enable staff to monitor activity on social media platforms and at the same time keep an eye on government servers.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / Oliver Berg / dpa

The danger is as invisible as it is real. Back in 2014, the Internet industry association ECO estimated that around 40% of computers in Germany were infected with malware. It is installed by criminals to profit from the compromised computers’ resources. The networks thus constructed – botnets – have the bandwidth and computing power needed to launch attacks on other computers and their network services. Over the past four years, the problem has grown rather than shrunk. In mid‑2018, IT security specialist AV-TEST registered around 350,000 new malware programs and potentially unwanted applications a day.

Large screens enable staff to monitor activity on social media platforms and at the same time keep an eye on government servers.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / Oliver Berg / dpa

The danger is as invisible as it is real. Back in 2014, the Internet industry association ECO estimated that around 40% of computers in Germany were infected with malware. It is installed by criminals to profit from the compromised computers’ resources. The networks thus constructed – botnets – have the bandwidth and computing power needed to launch attacks on other computers and their network services. Over the past four years, the problem has grown rather than shrunk. In mid‑2018, IT security specialist AV-TEST registered around 350,000 new malware programs and potentially unwanted applications a day.

Cyber defence from a plain-looking prefab

The task of identifying cyber threats in Germany is addressed by the Federal Office for Information Security (BSI), the only federal agency with a statutory mandate to conduct cyber defence operations. In the spartan environment of the Bonn headquarters, more than 900 experts monitor and analyse movements on the Internet. The 1970s prefab used to be occupied by a tyre company; the strict security checks at the entrance are the only sign of the new tenant. The Situation Centre on the fourth floor has an extra layer of security. Eibl looks over the two rows of desks where staffers watch the six large monitors. Among other things, they check that government networks are available and monitor mail flows on the servers of central government offices in Berlin.

More than 900 experts at the Federal Office for Internet Security in Bonn analyse movements on the Internet.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / Oliver Berg / dpa

But the focus is not just on reconnaissance; the political impacts of possible cyberattacks are also analysed. This calls for interdisciplinary cooperation between professionals ranging from IT specialists to political scientists. In front of one of the monitors is a critical infrastructure expert, tasked with ensuring the safety of vital facilities such as power plants and hospitals. However, BSI spokesman Matthias Gärtner says the risk of attacks on dams or electricity generating stations is lower than widely supposed. “We mustn’t overstate the threat. It is not possible simply to throw a switch and blow the whole thing sky-high.”

More than 900 experts at the Federal Office for Internet Security in Bonn analyse movements on the Internet.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / Oliver Berg / dpa

But the focus is not just on reconnaissance; the political impacts of possible cyberattacks are also analysed. This calls for interdisciplinary cooperation between professionals ranging from IT specialists to political scientists. In front of one of the monitors is a critical infrastructure expert, tasked with ensuring the safety of vital facilities such as power plants and hospitals. However, BSI spokesman Matthias Gärtner says the risk of attacks on dams or electricity generating stations is lower than widely supposed. “We mustn’t overstate the threat. It is not possible simply to throw a switch and blow the whole thing sky-high.”

Thousands of attacks a day on federal agencies

Two floors below the Situation Centre is the National Cyber Defence Centre – a meeting-place for all the major players involved in the search for online criminals, terrorists and spies. NATO and German intelligence services are also on board. This is where all the different threads of information come together. And it is a busy place. At the end of 2016, for example, the Internet sleuths succeeded in destroying the world’s biggest botnet infrastructure, Avalanche. The Avalanche bots had used phishing and malware to gain access to online banking. But even protecting government networks is a full-time job. An average of 1,700 infected mails a day are intercepted before they can be opened. The number of non-targeted daily attacks on ministries and federal agencies runs into the thousands.

For a long time, Internet security problems received only passing public attention, although the BSI has been operating since 1991 and the National Cyber Defence Centre was set up in 2011. Awareness changed suddenly, however, with the disclosures of ex-CIA employee Edward Snowden in 2013. They revealed that the NSA was even listening in to Chancellor Angela Merkel's mobile phone conversations. Merkel’s comment at the time: “Spying among friends is unacceptable”.

Chancellor Angela Merkel was shocked in 2013 when it emerged that the US intelligence agency NSA had tapped her mobile phone.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / Rainer Jensen / dpa

The second scandal to hit the headlines was in May 2015. Eibl remembers the day well. Hackers had managed to break into the IT networks of the German Bundestag and steal a still unknown number of documents and data. The system was evidently far less secure than the government networks. Parliament had been reluctant to assign the task of securing it to the government agency BSI. When crisis struck, however, the BSI experts were summoned to help. Although they managed to follow the hackers’ trail up to a point, the culprits’ identity still remains a mystery today.

Chancellor Angela Merkel was shocked in 2013 when it emerged that the US intelligence agency NSA had tapped her mobile phone.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / Rainer Jensen / dpa

The second scandal to hit the headlines was in May 2015. Eibl remembers the day well. Hackers had managed to break into the IT networks of the German Bundestag and steal a still unknown number of documents and data. The system was evidently far less secure than the government networks. Parliament had been reluctant to assign the task of securing it to the government agency BSI. When crisis struck, however, the BSI experts were summoned to help. Although they managed to follow the hackers’ trail up to a point, the culprits’ identity still remains a mystery today.

No horror scenarios but a long task list

The BSI experts’ job also includes protecting private individuals and businesses, especially small ones that cannot afford elaborate security systems. The agency informs them of possible threats and advises on how to handle them. It provides a non-commercial service and publishes its information on vulnerabilities. Eibl says many of his team passed up high-paying IT jobs in the private sector to work in public cyber security. In the coming year alone, the agency will recruit 350 new cyber experts. And with that growth it will soon be able to move into a new building. As threats increase, so does the need for vigilance. As the Situation Centre director knows: “No system is invulnerable”.

“The cooperation works very well,” says Nabil Alsabah, cyber security expert of the German IT association Bitkom. He applauds the fact that the agency has a high level of expertise, pointing out that “that is not the case in many other countries”. As regards the real threats posed by hackers, the security expert seems unperturbed. He sees the increase in attacks matched by improvements in cyber defence capability and thus regards the horror scenarios presented in certain movies as vastly exaggerated. None of them have happened yet, he says, “because we are better than we think”.

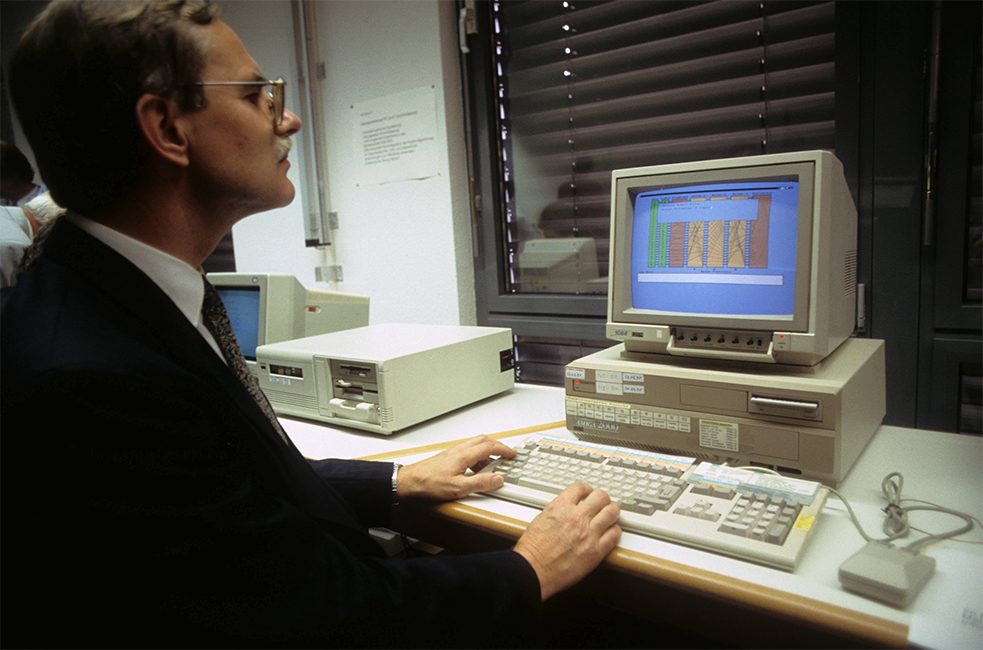

The BSI was established long before there was any real public awareness of Internet threats: a BSI staffer at work in 1992.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / Gisbert Paech / ullstein bild

BSI spokesman Matthias Gärtner believes the agency’s task list will lengthen considerably with the increasing digitalisation of business and private life. Driverless cars, networked home appliances, robotics and Industry 4.0 – all these developments create potential targets for spies and criminals. Protecting the underlying systems requires cooperation and thus a re-think by competing firms. “In the past it was virtually impossible to get two companies to sit down together and lay their cards on the table,” he says. That – he adds – has now changed.

The BSI was established long before there was any real public awareness of Internet threats: a BSI staffer at work in 1992.

| Photo (detail): © picture alliance / Gisbert Paech / ullstein bild

BSI spokesman Matthias Gärtner believes the agency’s task list will lengthen considerably with the increasing digitalisation of business and private life. Driverless cars, networked home appliances, robotics and Industry 4.0 – all these developments create potential targets for spies and criminals. Protecting the underlying systems requires cooperation and thus a re-think by competing firms. “In the past it was virtually impossible to get two companies to sit down together and lay their cards on the table,” he says. That – he adds – has now changed.