© Goethe-Institut Archiv

© Goethe-Institut Archiv

1971

GDR press campaign

A rumour creates a stir

During the period of German division, the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic also competed in the field of foreign cultural policy. In the 1950s and 1960s in particular, they competed for political alliances abroad in the context of the Cold War. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the conflict calmed down in the course of the policy of détente, but flared up again: The GDR press spreads the rumour that the Goethe-Institut is a spy institution.

In 1951 – the same year as the Goethe-Institut – the Herder-Institut in Leipzig began teaching German to eleven university applicants from Nigeria. In the following years, the GDR opened cultural and information centres abroad, thus competing with the Goethe-Institut in some host countries. Despite the policy of détente, the competition for German cultural sovereignty flares up once again when the GDR insinuates in a press campaign that the Goethe-Instituts abroad are nothing more than spy agencies of either the BND or the CIA – or even both. And anyway: the Munich headquarters was infiltrated by former Nazis, it was claimed as an allusion to the personnel continuity with the Deutsche Akademie. A year later, the mood has calmed down, but the competition continues until the fall of the Wall.

© Goethe-Institut Archiv

1972

Ian Kershaw at the Goethe-Institut Munich

A Brit becomes a leading expert on the Third Reich

Learn more

1972

Ian Kershaw at the Goethe-Institut Munich

A Brit becomes a leading expert on the Third Reich

A German teacher at the Goethe-Institut in his hometown Manchester awakens Ian Kershaw’s enthusiasm for German art and history. While attending a German course at the Goethe-Institut Munich, the British historian decides to focus his research on contemporary German history.

When Ian Kershaw meets the head of the Institute of Contemporary History Martin Broszat during an intensive German course at the Goethe-Institut Munich, the cornerstone is laid for an epic work of history. The British historian begins researching Nazi Germany at Broszat’s institute. Kershaw’s first book, “The ‘Hitler Myth’: Image and Reality in the Third Reich”, comes out in 1980 and serves as a basis for his celebrated, two-volume Hitler biography published in 1998 and 2000. Ian Kershaw is considered a leading expert on German 20th century history and is granted the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1994.

Photo: Michael Friedel

1974

Poster exhibition in London

The Staeck affair

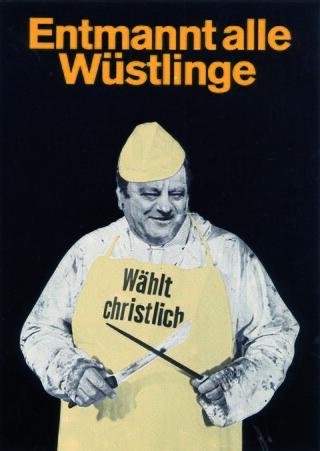

Artist Klaus Staeck creates a substantial political scandal with a poster exhibition in 1974. His depictions of German politicians was not at all well received and the Goethe-Institut was officially censured by then foreign minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher for financing the exhibition.

Under a banner reading “the Cold War is what gets us really hot,” Staeck portrays the then leader of the CSU Franz-Josef Strauß variously holding a shotgun or sharpening a knife. Too much satire for German politicians, who take umbrage that taxpayer money is used to insult them. In addition to an official censure, no more of Staeck’s exhibitions are to be funded. Authors Heinrich Böll and Günter Grass announce their intention to boycott Goethe-Institut events because they see its political independence under threat. Once the furore around the London exhibition dies down, they end their boycott and – like Klaus Staeck – continue to work with the Goethe-Insitut.

Photo: Michael Friedel

1977

Terrorist attacks on Goethe-Instituts

Bombings in Paris and Madrid

In the 1970s, the Goethe-Institut became the target of left-wing extremist attacks by the Red Army Faction (RAF) and the First of October Anti-Fascist Resistance Groups (GRAPO). While the attack in Paris was narrowly prevented, a bomb detonated in Madrid in 1977.

As early as 1974, sympathisers of the Baader-Meinhof Group occupied the Paris Institute. They hoped that this “solidarity action” with the RAF prisoners on hunger strike would attract widespread media attention. The occupation ends without bloodshed. In 1975, two bombs are discovered in the Paris Institute - just in time: it is assumed that the detonation was supposed to take place during evening classes and would have meant hundreds of deaths. A confessional call points to the RAF as the author. In 1977, Madrid was hit: the institute was the victim of a bomb attack by the left-wing extremist underground organisation GRAPO; the east façade of the building was badly damaged.

Photo: Michael Friedel

1985

The pope at the Goethe-Institut

With God’s blessing

We’ve got the pope! Future Pope Francis learns German at the Goethe-Institut in Boppard. To this day, he continues to exchange letters with the family he sublet from at the time. The institute in Boppard has since closed, but memories of the pontifex live on.

Jorge Mario Bergoglio, who became the 266th Bishop of Rome and thus the pope on March 13, 2013, comes to Germany in 1985, where he attends the Sankt Georgen Graduate School of Philosophy and Theology in Frankfurt and learns German at the Goethe-Institut in Boppard. During his stay in the Middle Rhine Valley, the then 48-year-old, like many other Goethe-Institut students, sublets from Helma and Josef Schmidt. The Schmidts and the current pope have been pen pals ever since. In handwritten letters, Bergoglio looks back on his time in Boppard and thanks the Schmidt family for their hospitality – in German, of course.

Photo: Michael Friedel

1987

Rudi Carell causes a diplomatic incident

How a spoof results in the closure of the Goethe-Institut Tehran

Learn more

1987

Rudi Carell causes a diplomatic incident

How a spoof results in the closure of the Goethe-Institut Tehran

In his comedy show, “Rudis Tagesshow,” Rudi Carell makes fun of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s founder Ayatollah Khomeini in a sketch, causing a diplomatic row with Iran: Not only are German diplomats expelled; the Goethe-Institut is also forced to close.

Not everyone finds it funny when, on the eighth anniversary of the Iranian Revolution, Rudi Carell depicts Ayatollah Khomeini being pelted with women’s underwear in a spoof. The day after the broadcast, Iran demands an apology from the German government, expels two diplomats, and cancels all flights to Germany. The Goethe-Institute in Tehran is also forced to close. Rudi Carell apologizes for the clip. The ARD has never broadcast the sketch again.

Photo: Bernhard Ludewig