"Tanz in August"

Bollywood in a Township

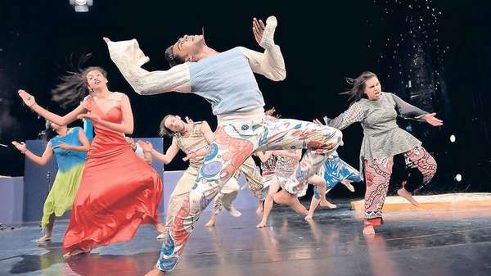

“Tanz in August”: Constanza Macras triumphs with the multiethnic piece Chatsworth.

One of the discoveries at Tanz im August was Euripides Laskaridis. His piece, Titans, is a laugh-out-loud fragmentation of a myth. Both of the titans that plunge across the stage of HAU2 in absurd actions aren’t powerful giants, but rather ridiculous shapes. Laskaridis, with an egghead, a cheeky nose and big belly, plays the female deity. His titan is a chickpea.

She wonders through the dark stage cosmos giggling in wonder. She looks at the stars or bends over a tiny mountain formation made of gold foil. She aborts the work of creation to get back to her homework. When the titan gets dressed up to look for a mate, trying to flirt with the somber Dimitris Matsoukas, it’s absolutely hilarious. Laskaridis shrinks the titans to human size in his grotesque theater of images. And the audience amuse themselves endlessly.

Audience members also almost fell out of their seats laughing for Constanza Macras, who premiered Chatsworth at HAU1. Chatsworth is a township in South Africa that was built by the apartheid regime in 1960. This is where Indian immigrants were ghettoized. Macras has put together an amazing, multi-ethnic ensemble for the piece. The Indian performers from South Africa are all ravishing. With Manesh Maharaj, there’s even a veritable of traditional Kathak dance on stage.

Splinters of theory and biographical stories.

The black South African dancers and the Berlin performers from Macras’ group, Dorky Park, are also splendid. At the outset, a video shows the painted matchbox houses of Chatsworth, which are typical of townships. The indians were forced into these tiny boxes to moderate their rate of growth, one of the performers explains. However he refers to the Indian migration to South Africa, which goes back to 1860, as an economic success story. The Indians used their chance. Avishka Chewpersad is the opposing critical voice. She accuses the Indian community of “obsessive particularism” for the way they cling to their own cultural identity. Splinters of their and political discourse are woven into biographical stories, which represent life in the diaspora.Maharaj speaks of his grandmother, who immigrated to South Africa in 1906. The widow with two sons worked growing vegetables, like many Indians did. They tell of a rich patriarch who swore off all earthly pleasures to become a monk and go on a pilgrimage. And of a man who can’t be open about his homosexuality. Deals between the different ethnic groups are negotiated in pantomime - each of them trying to pull one over on the others.