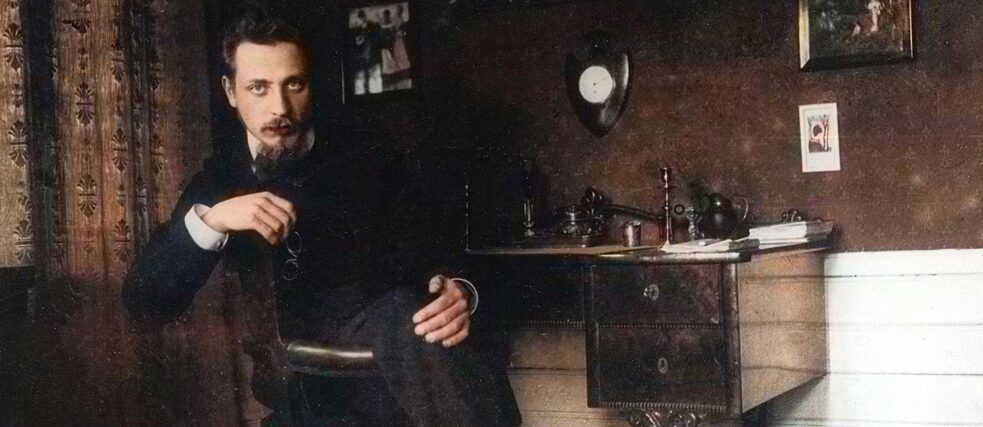

Rainer Maria Rilke

150 years of Rilke: A poet and his ambivalence

Rainer Maria Rilke, one of the most influential poets of literary modernism, was born 150 years ago. In this interview, literature professor Sandra Richter discusses what shaped him as a person and why engaging with his work is still worthwhile today.

Ms Richter, on 4th December, we will mark Rainer Maria Rilke’s 150th birthday. How might he have celebrated the occasion?

When Rilke was young and had little money, he celebrated his birthdays in simple ways – with strawberries and postcards on the table, such as one of the Nike of Samothrace. Little is known about his later birthdays. Perhaps he would have taken a long walk in the countryside, enjoyed a good meal and spent the day in the company of friends, engaging in conversation.

In your book “Rainer Maria Rilke; Or, an Open Life”, you present a new picture of the poet. What kind of person was he?

In his youth, Rilke was an exceptionally jovial person, but he knew that he was physically not suited for what was expected of him: a career as an officer. From an early age, he was passionate about art and consistently chose the life of an artist, pursuing it despite other inclinations and against the wishes of his father. He was a likable, humorous person, but at the same time a disciplined artist, wholly devoted to his work.

On what sources do you base this?

In 2022, the German Literature Archive in Marbach was able to acquire Rainer Maria Rilke’s private estate. I spent three years working with this collection, and this was a truly wonderful experience. It allowed me to see the young Rilke in an entirely new light, as well as the Rilke who gradually gained recognition, moving through the salons of Central Europe and establishing himself as a key figure in art and literature.

Which new insight surprised you most?

His ambivalence was striking. He was an artist who was creatively prolific, bringing joy to all those around him. But he could also hurt people so profoundly that they completely turned away from him. This was true of almost all the women and female friends in his life. Many of them were in love with him, yet served as his muse only for a few weeks before he set them aside.

Rilke was always surrounded by women. What roles did they play?

The women who had a lasting presence in his life often played multiple roles. They were frequently lovers at first and were worshipped by him. But later they slipped into more maternal roles, figures Rilke regarded as “chosen mothers”. He was surrounded by strong women: his wife, Clara Westhoff, an outstanding sculptor; his lifelong friend and writer Lou Andreas-Salomé; and the painter Baladine Klossowska.

Rilke supported young female writers. You write that some of them were dependent on the recognition of the established author. Do you think Rilke might be “cancelled” today, in the age of #MeToo?

The moral standards were different at that time, and yet Rilke’s publisher still felt compelled to defend him against rumours that he might have acted inappropriately towards girls. Rilke adored girls – a term that could include everything from young children to unmarried women. He revered them as asexual figures, although he did sometimes experience desire for them. At the same time, they embodied the very essence of art for him. He sought to support young female artists, not always selflessly, and he himself drew inspiration from female role models. He translated works by women writers, including the poets Sappho and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. For him, these women were morally far superior to men.

Women are also said to have played a role in Rilke's health. After all, he was sickly throughout his life.

Rilke repeatedly sought help, especially from his “chosen mothers”, who would then send him to doctors. Lou Andreas-Salomé advised him to walk barefoot, eat healthily and undergo spa treatments. Rilke frequently followed this advice. He adhered to a vegetarian diet, abstained from alcohol and made an effort to stay active, hoping to cure himself of the many ailments and weaknesses he felt he had.

You write that Rilke saw himself as a flawed being.

From his youth, Rilke was psychologically and physically very fragile. Some said that from behind he looked like a “girl”. He was indeed very slender and had sloping shoulders. And every woman who knew him wrote the same sentence in their memoirs: “He was ugly.” Apparently, however, he had other gifts. He was an attentive listener and had a beautiful, deep voice, which made people enjoy listening to him.

Despite everything, Rilke always rejected psychoanalysis. Why was he afraid of it?

Rilke was afraid psychoanalysis would turn him into a “disinfected soul” – and disinfected souls would have nothing left to write poetry about. He valued the unsettling, the strange, the seemingly sick. That was the material for his writing: his fears, his desires, everything that remained unfulfilled. All of this became the substance of his poetry. He saw himself as a kind of aesthetic Christ, suffering on behalf of others.

Although Rilke saw himself as Christ the Redeemer, he criticised the megalomania of others, and warmongering. Today, we again live in times dominated by power-hungry men, and unfortunately, by wars. How can Rilke’s work help us?

Rilke could write with pathos, and he could write polemically. He applied both approaches to the politics of his time. When the First World War began, he was briefly inspired and he expressed this in his passionate, lofty verses. He admired how people rose up, turned towards high ideals. But shortly afterwards, his disgust for the war grew. The First World War left him unable to write for a long period. In his letters, Rilke polemicised so strongly against empires that you might think you were reading the words of a radical leftist. He railed against domination and attempts to seize territory and power. In this respect, Rilke’s emotional responses offer a moral guide. He first engages fully, then he returns to what he considered the essence of humanity. And for him, that essence was not war or violence, but emotional connection.

Rilke was a European writer, deeply connected both to his native Prague and to many other countries. Today, Europe faces great challenges. Can Rilke offer us comfort in these times?

He certainly would have wanted to. For Rilke, Europe was a single, shared homeland. He came from the East. Czech was not his native language, but he could understand it. He knew Russian and could read the Scandinavian languages. Italian and French were not a problem, and he could also get by in Spain. These were countries of real cultural significance to him. Before the First World War, he could travel without a passport – an experience that deeply fascinated him.

What makes Rainer Maria Rilke feel modern even today?

He is an artist who uses language in a way that is unparalleled. He creates striking verbal images and rhythmic verses that are truly astonishing. He can write sentences that read like aphorisms, yet almost dissolve when you engage with the full text. Take, for instance, the famous line “You must change your life” from the poem Archaic Torso of Apollo. His enduring strength lies in his bold, playful use of language, precisely because this way of writing continues to resonate so deeply with readers.

You said we need Rilke today more than ever. How so?

Because today we often use language carelessly. Rilke had the ability to offer us new expressions and innovative metaphors. In an age of AI, in a world dominated by repetition and the banal, his approach can reveal entirely new worlds to us.

Lady Gaga even has a tattoo of one of Rilke’s maxims. He’s also trending on TikTok. How do you explain Rilke as a pop-cultural phenomenon?

Rilke has often spoken to young people because his work offers comfort and guidance. The emotional impact of his texts is incredibly important. His Letters to a Young Poet continue to resonate strongly with young readers today. Lady Gaga has a passage from it tattooed on her upper arm. These letters address the question of how to become a great artist: one must feel the calling and dedicate oneself entirely to it. Texts like these still captivate young people.

What, in your view, would Rilke find shocking about today’s world?

Definitely the state of the environment. This deeply concerned him even in his own time. When a factory opened nearby, it disturbed him greatly. The way we treat the natural world today would almost certainly alarm him.

And what might have fascinated him?

He would probably have been thrilled by the chance to see and explore the world – up to the point where travel becomes overwhelming and trivial, because one cannot fully grasp every culture, and some regions of the world risk descending into barbarism and inhumanity. He would certainly have been fascinated by the considerably expanded possibilities of curing diseases, and perhaps the illness that led to his death could also have been brought under control, namely leukemia.