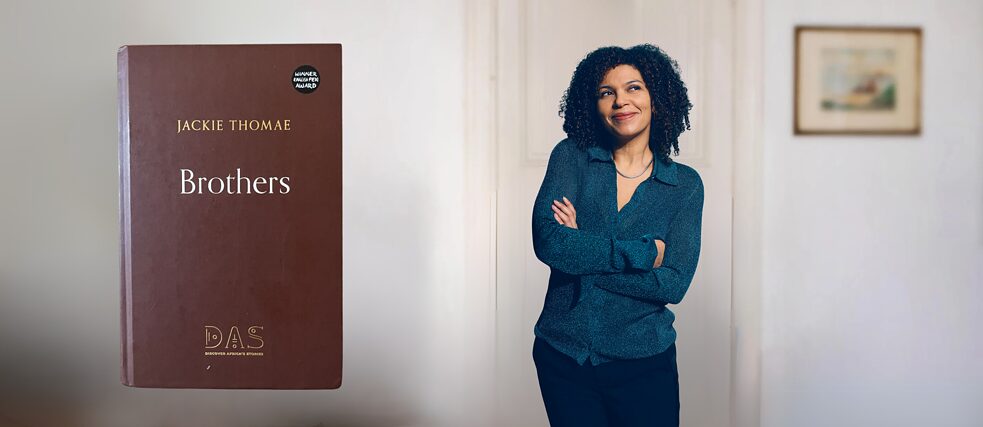

Jackie Thomae

Brothers

Two Half-Brothers, Different Destinies, and One Reunified Country – Jackie Thomae’s Brothers Documents Lives in a Germany Under Transformation.

By Prathap Nair

The year 1985 in many ways served as a pulsating precursor to German reunification. West Berlin rolled out the red carpet for Princess Diana and hosted legendary parties at the celebrated Dschungel club. Across the Wall, young East Berliners breakdanced to Beat Street at the Kosmos Kino, eager to escape from the shackles of authoritarian surveillance. On both sides, there were signs of an advancing liberation and a promise of change.

Amid these exciting times unfolds Jackie Thomae’s sprawling novel Brothers. It orbits two half-Senegalese brothers living in the GDR, Mick and Gabriel - born to the same father but unaware of each other’s existence. Mick is a waywardly philanderer who runs a club with his friend. For him, life is a series of hastily organized parties where drugs and alcohol blur consequence. Mick runs the risk of being a borderline womanizer but mostly ends up as a ladies’ man. “At red (traffic) lights, he’d flirt with ladies, try to catch their eye, and almost always managed it, even women with their husbands, or with children, or women in headscarves,” writes Thomae. Gabriel, his polar opposite, is a disciplined architect building a career in London.

Thomae’s Brothers invites readers to ponder what shapes a person’s destiny - external social circumstances, individual actions or pure coincidences. Although the novel is set in the sunset years of GDR and Germany’s difficult reunification, Thomae’s novel is not overtly coloured by the geo-political events. Instead, it’s preoccupied by the notions of race, sexuality, nationality and class through the lives of its protagonists who are uniquely positioned to offer social commentary. Hence the personal here is political.

The messy lives of human beings

Brothers investigates the messy lives of ordinary human beings like Gabriel and Mick. While it doesn’t shy away from discussing race - both protagonists are mixed race men in a predominantly white European society - the tone remains refreshingly optimistic. Referencing to Delia, his girlfriend, Mick thinks: “And why shouldn’t she be allowed to nod like a scowling Black dude. The world was diverse and tolerant. The world was upside down.”The novel’s narration is worth mentioning. While Mick’s portions are written in a close third person, Gabriel’s is told through the first-person perspective alongside chapters where his girlfriend, Fleur’s, voice channels his anxieties of living as a black man in London. Yet, Gabriel’s black identity doesn’t define him because he is a man of the world. And so when Fleur asks whether he has ever been to Africa, Gabriel replies, “I have no special interest in Africa. I have an evenly distributed interest in the whole world.”

Both brothers, stark as chalk and cheese they are, learn to navigate the question of race by seizing their place in societies that are unsure how to receive them. Race doesn’t consume them or keep them awake at night. This is perhaps Thomae’s quiet triumph: she shows how identity can be claimed without being defined by struggle.

In one of the novel’s most insightful passages, Gabriel reflects on how he belongs in the society that he lives and works in: “And suddenly I was white. Not that the tabloids explicitly described me as White. They didn’t need to. I became White when they refrained from writing that I wasn’t.

Anatomy of a Fall

German division and reunification have been explored exhaustively in popular culture - from Anna Funder’s Stasiland to movies like Good Bye, Lenin!, and TV shows such as Weissensee or Deutschland 83. Yet few contemporary works examine the immigrant experience in the DDR where thousands of contract workers from countries like Vietnam, Cuba, and Mozambique lived under precarious situations. Thomae’s Brothers stands apart by illuminating this overlooked perspective.Spanning four decades from 1985 onward, Brothers is both spectacularly imagined and lucidly rendered. Rather than braiding Mick and Gabriel’s narratives together, Thomae splits the stories of the brothers into two separate segments. This offers the readers two standalone novels rolled into one – remarkable in scope and intimacy. Neatly tying narratives up, the book ends with a poignant Epilogue featuring their absent father, Idris.

Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp’s translation preserves the book’s substance without diluting its somber tone from the original version and understated dealing of touchy subjects. Its thanks to Kemp’s clear-eyed and precise use of language that the novel comes alive - the Berlin club scene in the 90s, and London’s well sanitized white-collar set up.

Brothers was shortlisted for the Deutscher Buchpreis (The German Book Prize) in 2019, and Jackie Thomae will tour the Goethe-Institut in India, introducing the book to an Indian audience.

Jackie Thomae was born in Halle/Saale in 1972, grew up in Leipzig, and moved to Berlin in 1989, where she still lives today. She is a journalist, television writer and author. Thomae’s first book publication, the guidebook Eine Frau – Ein Buch (2008; tr: One Woman – One Book), written together with Heike Blümner, became a bestseller. Brüder (2019; tr: Brothers), Thomae’s second book, is a large-scale novel about the lives of two very different brothers that critics have often compared to Anglo-Saxon-style social novels. Die Zeit wrote, That the issue of skin color and racism is more complicated than social-justice warriors think, is shown in this observationally powerful social novel. Brüder was on the shortlist for the German Book Prize in 2019 and was awarded the Düsseldorf Literature Prize in 2020.