Genre

What are Travel Comics?

Travel comics are a genre of graphic literature that has been gaining popularity recently.

By Vladimir Lopatin

What exactly are travel comics?

The answer is quite simple. For the most part, travel comics are lively, reality-based stories and adventures that authors and illustrators experience on their journeys. Travel albums have been around for some time and we’ve become accustomed to them: we write down our travel adventures, glue museum tickets or railway tickets in them, note the places we’ve been, strolled and had coffee. In recent years, however, people have begun to turn these collections of drawings, museum and railway tickets into full stories. Sometimes they contain street scenes, sketched hurriedly in a café, funny dialogues or situations, but sometimes a whole day or a whole journey is sketched.

Let’s talk about the pros and cons of this format.

In my opinion, the biggest disadvantage of travel comics is that they often lack well-thought-out, complete subjects and the story appears “fragmented.” Such comics are typically drawn on the go when the maker has a little free time, under conditions that are not exactly ideal: on the coach or train, in a cafe where they have a quick snack, or before going to bed, because at other times the authors are just ordinary tourists. They ramble through the city, taking in its history, spend time in museums, talk to people – leaving very little time for drawing. Many authors prefer less extensive subjects; modest sketches that reproduce actual situations. This creates a kind of hub for smaller events. It is difficult to perceive such “hubs” as coherent stories; they’re more like collages of events and experiences.

Travel comic by Lena Mursina (fragment)

| Lena Mursina /creamsodaorchestra

Travel comic by Lena Mursina (fragment)

| Lena Mursina /creamsodaorchestra

After the journey

Some only start drawing after the journey is over. In doing so, they run the risk that the colours of the first impression will pale and some details will be lost: they are tracing mere memories and photos. This approach certainly has its disadvantages; no memory is able to store a whole day with all its details for a week, especially if the day was very eventful. So, the author begins to think up dialogues; the dynamics of the plots diminish. In this situation, travel notes, brief reports and sketches can be helpful. The big advantage of this approach to drawing a travel comic, however, is that you can establish a smoother and more complete subject and add a main idea to the journey that ties the whole story together.

I believe that if you put the story together some time after your return based on photos and notes, it will be much more difficult to reproduce the impressions so they are as colourful and fresh as they actually were. The task is not at all easy: you bring home an enormous number of events in your memory from a journey, which then have to be sorted and structured while not losing the feelings, experiences and impressions. In this regard, the “draw while traveling” strategy is definitely beneficial.

Big art

Travel comics by Russian authors are usually not particularly long: one to 10 pages. Little books of around 30 pages are quite rare.

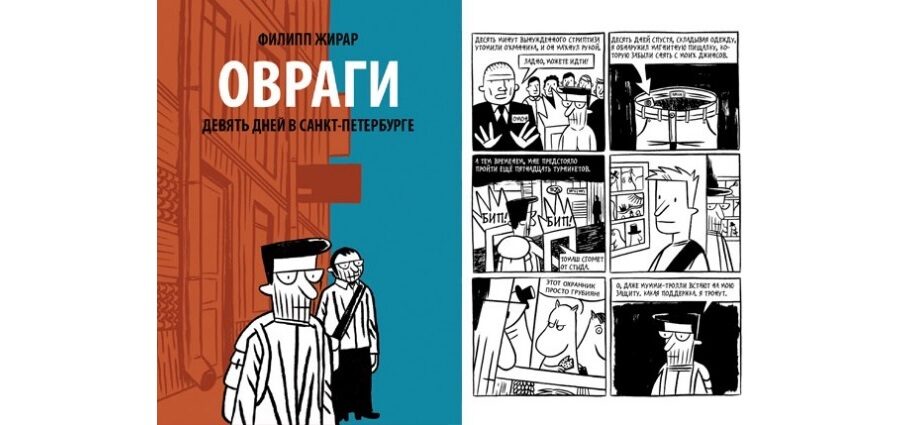

At this point, of course, we have to mention the bigger graphic novels in which authors take us with them on a journey: Shenzhen or Pyongyang by Guy Delisle (Drawn and Quarterly), Ruts & Gullies: Nine Days in Saint Petersburg by Philippe Girard (BDANG), and of course Joe Sacco’s Palestine, a travel comic in the spirit of comic journalism (Fantagraphics Books).

Sadly, no Russian authors have yet produced anything this major for the domestic market.

Ruts & Gullies: Nine Days in Saint Petersburg by Philippe Girard (BDANG)

| Philippe Girard, Ruts & Gullies: Nine Days in Saint Petersburg

So what makes this type of comic so appealing? These are pure emotions, the author’s impressions, lively fragments of the journey and unusual situations that the author has experienced and wants to keep in mind. We take a camera with us on a journey for the same reason; we want us to remember the journey for several years, to five or ten years later go through the photos, immerse ourselves in memories and sigh, “That was so cool!” An artist creates similar memory anchors – not only with the help of photos and videos, but with the help of drawings and comics. Artists naturally have options that photo and video cameras don’t: An artist who goes on a journey can document what’s never seen by a camera lens, funny dialogues, jokes, thoughts or events that suddenly happen.

Ruts & Gullies: Nine Days in Saint Petersburg by Philippe Girard (BDANG)

| Philippe Girard, Ruts & Gullies: Nine Days in Saint Petersburg

So what makes this type of comic so appealing? These are pure emotions, the author’s impressions, lively fragments of the journey and unusual situations that the author has experienced and wants to keep in mind. We take a camera with us on a journey for the same reason; we want us to remember the journey for several years, to five or ten years later go through the photos, immerse ourselves in memories and sigh, “That was so cool!” An artist creates similar memory anchors – not only with the help of photos and videos, but with the help of drawings and comics. Artists naturally have options that photo and video cameras don’t: An artist who goes on a journey can document what’s never seen by a camera lens, funny dialogues, jokes, thoughts or events that suddenly happen.

story of the place.

Human memory mustn’t be overestimated. Our journey, which seemed so incredibly colourful and full of events, begins to pale after a month or two. Then the comics drawn during the journey come to the rescue. Although such comics have their drawbacks and authors see much more in them than readers do, I still hope that illustrators won’t stop making them.

Furthermore, such comics are valuable in the sense that they tell not only the story of the traveller but also the story of the place. The artist reports on a country or city that is new to them; they would like to share their thoughts and impressions of this place, what they’ve seen and learned about the place, with others who haven’t been here. The comic becomes a little “tour” and the illustrator becomes a travel guide.

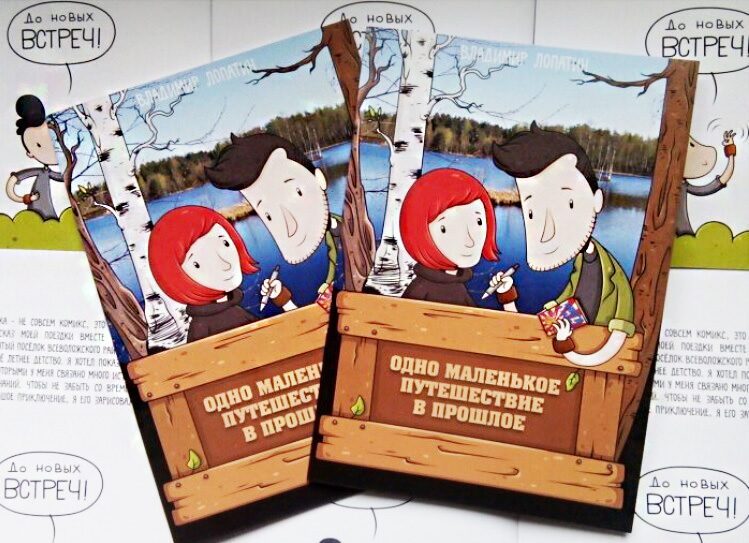

“A Brief Journey into the Past” by Vladimir Lopatin

| Wladimir Lopatin /piterskii_punk_wall

What would you have to do to develop short travel notes and emotion-filled sketches into large, complete stories about travel?

“A Brief Journey into the Past” by Vladimir Lopatin

| Wladimir Lopatin /piterskii_punk_wall

What would you have to do to develop short travel notes and emotion-filled sketches into large, complete stories about travel?

I have a couple of tips; perhaps some of them may be useful for those who’d like to draw an interesting story in this genre.

- It’s best not to travel alone, but in the company of others. Even a duo makes the journey much livelier: dialogues and reactions to different situations offer more interest. And it’s just nicer not to be alone.

- Take a notepad with you, draw at every opportunity, try to preserve the mood of the moment.

- Try to take notes during the day: what you experienced here and there, something funny someone said, interesting situations and information. Because in the evening it becomes more difficult to precisely remember an eventful day.

- If there was no opportunity to draw during the day, draw in the evening. Try to at least document the most important and essential things, as long as the emotions and memories of the day are fresh. The next day will bring new impressions.

- Collect museum tickets, interesting advertising brochures, business cards and other materials on paper. Build them into the story to make the comic livelier and closer to reality; you as a “travel guide” tell more about the place with these materials. Tram tickets tell the reader what the journey cost, promotional materials from the bar invite the reader to join you, etc.

- When you’re out and about, take photos. Lots of photos, especially of what you want to draw: rubbish bins, traffic signs, people, buildings – everything you might need.

- If you didn’t manage to finish drawing everything during the journey, don’t put off this task; do it while the emotions are still there.

- And now look at the result, look at what you’ve drawn along the way, and it will become clear to you: it’s not yet a complete work, but a basis for one. Now it’s time to sit down and get down to business on a great, full comic. After your material has been creatively revised, a cool, interesting story may emerge with a coherent subject and a guiding principle – a great travel comic in all respects that everyone will like.

Travel, draw and everything will be alright!