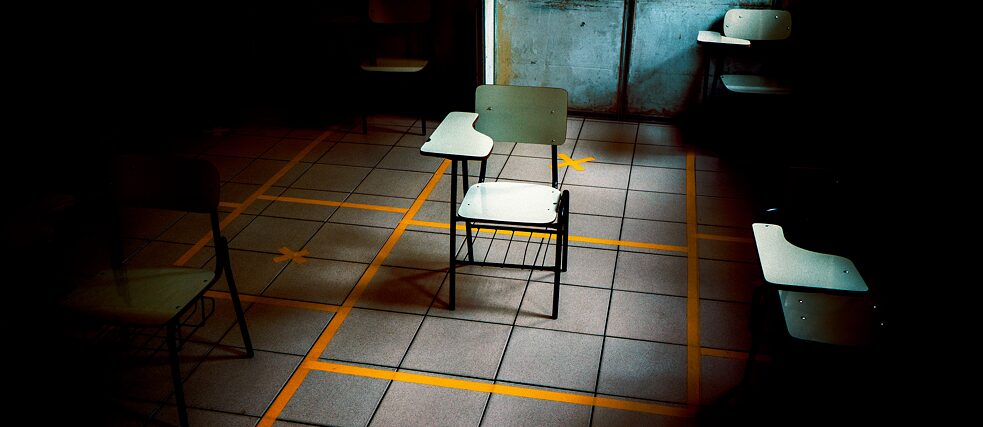

Post-Pandemic Education

“It was not lost time”

In Brazil, isolation caused by the pandemic also brought schools and families closer together. Christiane Sampaio describes, how teachers became more aware of the realities of children’s lives, and how urban public spaces came to be seen as more important for socialisation and conviviality.

By Christiane Sampaio

The pandemic, although revealing a world fraught with crises and structural inequalities, has also provided lessons. In Brazil, school closures in an effort to reduce the COVID-19 transmission brought teachers and families significantly closer together – something that has the potential to impact the education system in a sustainable manner. Teachers became more aware of the realities of Brazilian children’s lives. At the same time, school and urban public spaces came to be seen as more important for socialisation and conviviality.

“Teachers made an enormous effort to connect with families, even those who did not have access to the internet. There was an opportunity to understand where the family was coming from, their difficulties, challenges, and diversity,” ascertains Maria Thereza Marcilio, regional coordinator for the Americas of the Global Leaders for Young Children Programme at the World Forum Foundation and founding president of Avante – Education and Social Mobilisation, an NGO for education and social transparency which has been working in the field of education in Brazil for 25 years.

Marcilio reminds us that the relationship between school and family has always been tense in Brazil, particularly in at-risk areas with greater social vulnerability. “School tends to view parents as burdensome. As if families undid the work the schools have done. On the other hand, families do not feel accepted, and, for that reason, remain on the defensive. That saying about how it takes a village to raise a child does not actually work in practice because a more open dialogue of mutual trust is lacking,” the researcher points out.

Little Space for Educators

It is still early to determine what impacts consciousness and awareness will be able to have on schools’ political-educational projects and teaching practices. “It must be understood that the instructor is embedded in a network which is sometimes constraining and conditional,” as Maria do Socorro Nunes points out. She is a national coordinator of a research project of the collective Alfabetização em Rede (Online Literacy) about remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic, which connects 29 universities in Brazil and has reached 14,730 primary education teachers in 18 of the country’s states.According to the researcher, the most effective actions that are being developed are those in which teachers work with their school teams to think of alternatives and possibilities taking into consideration each child’s specific characteristics. This implies also identifying who does or does not have access to remote learning through technology. “Often the material arrives ready and provides a framework for the professor, making it impossible for him to implement his own pedagogical practice and develop activities based on his expert knowledge of the children,” Nunes explains.

New References

The research, whose methodological design was built by the Alfabetização em Rede collective, reveals that school and family came to interact not only from new digital reference points, but also physical ones. “Teachers made use of a wide variety of resources, like PDF books or storytelling videos sent via whatsapp. For families who did not have internet access, small bags with physical books, which normally stayed packed away in boxes out of circulation in school libraries, were distributed.”Nunes further states that, since that literacy activity, literature became part of the families’ routines. “Even if the parents are illiterate, nothing impedes them from connecting with a book. Reading is not limited to decoding. There are many ways of reading, and children read in various ways. The children’s literature book is a fundamental tool for the child to become aware of written culture,” the researcher explains.

Rethinking Routines

Marcilio mentions that the pandemic has taught us something else which has to do with the importance of being flexible and bringing the experiences we had during isolation into the school. “I am seeing people talking about recovering lost time and accelerating. It was not lost time. Everyone was living and learning because people do not learn only in school. You cannot speed up life and learning.” According to the consultant, there is a need to reconsider everything in school: “Rethink routines, age groupings, materials and the uses of spaces and environments both inside and outside the school.”Isabella Gregory, coordinator of the MOB.PI programme for urban planning and child participation at the CECIP (Centre for Creation of the Popular Image), cites the example of Alcinópolis, in Mato Grosso do Sul, which reclassified the surroundings of schools around the city based on children’s listening processes. A cross-sector team – involving the departments of environment, public works, education, health, social services, in addition to the mayor, his chief of staff, other civil servants, public safety, and the parent-teacher association – was mobilised.

The transformations began with the construction of toys using recycled wood in the open spaces of some schools – an activity in which school bus drivers and janitors participated. “The pandemic affords us opportunities to transform the city, to make it a more human and playful place,” says Marieta Colucci, who also works at MOB.PI as an urban planning consultant. Gregory und Colucci, both believe that occupying public space needs to be rethought from a cross-sectoral perspective that takes multiple views into account. “What would a child-friendly city be like? We always like to recommend thinking of some spaces in the neighborhood, taking into consideration how the caregiver and small child get around.” Nine Initiatives similar to that of Alcinópolis and coordinated by MOB-PI were carried out until September 2020.