Belarussian Art in Poland

A Journey to Białystok

On the Polish border to Belarus, Belarusian artists exhibit art which they would no longer be able to show in their homeland. Around the corner is the war in Ukraine. The “taz”- journalist Julia Hubernagel went there for first-hand impressions.

By Julia Hubernagel

The train that travels to the northeastern edge of Poland on this last day in March is half empty. It seems as though no one wants to travel towards the east, towards the Russian Federation and the border with Belarus at the moment.

A few days later, on the way back, it’s a completely different picture: several weeks after the outbreak of war, the trains in Poland are still full of Ukrainian refugees. Silent children look blankly out of the window of the intercity, just like their parents; between them are dogs and cats, also mute. It’s hard to imagine what they have seen in the last few weeks; many have no more than a small rucksack with them.

The exhibition

Poland, not normally known for its friendliness towards foreigners, welcomes the refugees from the Ukraine with a willingness to offer help and support. Approximately 2.5 million Ukrainians are currently in the country. Even here in the province of Podlaskie, the destination of this journey and the most north-easterly Voivodship (administrative district) of Poland, which is not exactly on the refugee route to the West, several thousand people have arrived.Two years earlier, however, this region experienced a much larger wave of immigration from another neighbouring country. In Białystok alone, the capital of Podlaskie, around 10,000 people fled from Belarus at that time. In summer 2020, the Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko claimed victory in an election whose result was clearly manipulated. And Belarus experienced the largest mass protests since its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991.

No democratic upheaval in Belarus

“The broken clock of our history has been rattled by flash grenades. Now its ticking is both deafening and breathtaking,” wrote the Belarusian writer Julia Cimafiejeva in her diary in August 2020, still hoping for a democratic breakthrough. However, Lukashenko’s dictatorial regime suppressed the demonstrators with full force, with the support of Moscow. Today the population of the former Soviet republic is more oppressed than ever before.Somehow or other, the vicious circle of sham elections and protests plays out every five years, said curator Anna Karpenko in Białystok. In partnership with the Goethe-Institut Warsaw and the Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst Leipzig, the Galeria Arsenał is showing contemporary Belarusian art in the exhibition When The Sun Is Low - The Shadows Are Long.

The border between Poland and Belarus is only approximately 50 kilometres away from here. But it is difficult to cross. Trains haven’t run across the border for a long time now; aircrafts from Belarus are no longer allowed to land in EU countries since the Lukashenko regime forced a Ryanair plane carrying the regime-critical blogger Raman Pratasevich to land in Minsk. The artists from Minsk who travelled to the vernissage in the east of Poland therefore had to fly via third countries such as Turkey or Armenia. In one case, even via Belize.

It is actually quite dangerous for the artists from Belarus to take part in the exhibition in Białystok, Poland. The repressive character of the Lukashenko regime is explicit. Yet, the artists do not want to be silent. Lukashenko has lots to do, says Bazinato, smiling ironically. And, they are only artists anyway. It is a courage born of desperation from people whose country was recently used by Putin’s army as a deployment zone for the invasion of Ukraine and in which people can be arrested in broad daylight because they wear white trousers with a red jacket.

Living in Minsk

But in light of the brutal murders that are taking place in Ukraine, Belarus’ neighbour to the south, staying silent appears to be less of an option than ever, despite the danger. That’s also the view of Masha Svyatogor. In her collages, the artist portrays life in Minsk and tells of growing up in one of the giant tower blocks on the outskirts of the Belarusian capital.The sleeper areas may be monotonous and unattractive, but one feels safer there than in the centre, she says. “You can evade the eyes of the regime better there than along the large boulevards of the city centre.” Leaving Minsk is fundamentally not an option for her.

Many of the artists exhibiting their work in Białystok have already turned their backs on their homeland of Belarus. Curator Anna Karpenko dreams of returning to a free Minsk. Since the suppression of the protests in autumn 2020, she has lived in exile in Germany. In order to be able to stay, she applied for a student visa, although she has a degree in philosophy and sociology and does not need another one. There’s generally not much help for Belarusians who have to emigrate, she says. “To Europe, our country is still a blind spot.”

Belarus has a population of 9.4 million people; its diaspora outside Russia and the United States is somewhat fragmented. An exhibition with Belarusian art abroad is a rarity, although it’s not the first time for the Galeria Arsenał.

Crowds of visitors at the vernissage

During the vernissage, a curator from the USA who lives in Poland emphasises that the existence of these galleries far outside the capital is a rarity in conservative-Catholic Poland. On the opening evening, the gallery is packed; visitors press against each other. Unmasked: the virus was basically abolished by law in Poland a few days ago.The Polish-Belarusian border region is thinly populated. Most of the people here vote for the conservative PiS party. In 2020, many of the Belarusian refugees were nevertheless welcomed with friendship, says Maciej Chołodowski, who works as a journalist for the Gazeta Wyborcza. His face is hard to read as he says this, gazing out of the window in front of which the snow lies several centimetres high. But the border to Poland is not only difficult for Belarusians to overcome.

Refugees in the border forests

Between the two countries there is a thick forest, one of the last surviving primeval forest regions in Europe. Wandering around there, almost forgotten owing to the new crises, are still the poorly equipped refugees from Syria, Iraq or Afghanistan, whom Lukashenko flew into Belarus in order to put pressure on the European Union.No one knows how many of them are still holding out there. Chołodowski says that many of his compatriots believe the state propaganda that there are many terrorists among the Muslim refugees. Anyone who wants to help, he says, is liable to prosecution.

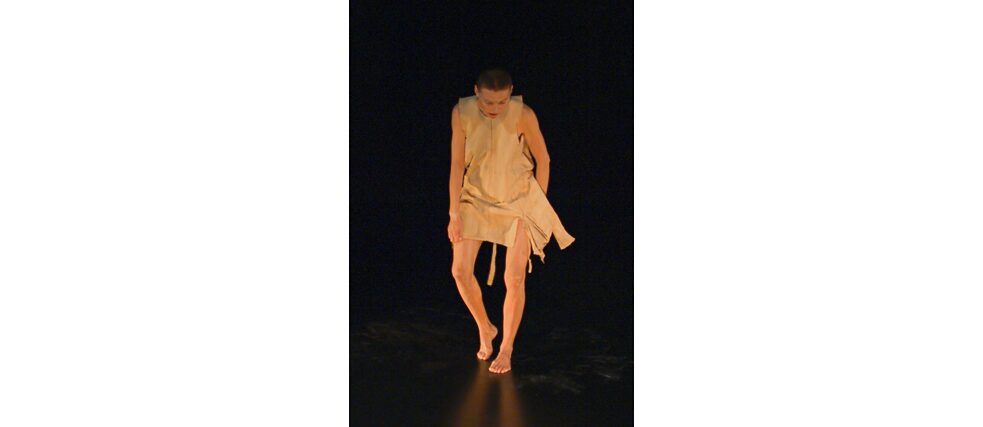

One of the Belarusian artists addresses the situation in the border forests in his work. In his video piece, Jura Shust, who lives in Berlin, uses drone recordings of the Polish border force and refugees’ mobile phone videos in seamless succession. The recordings speak for themselves: refugees who build makeshift shelters in the forest, displaced, trapped in a conflict between the East and West.

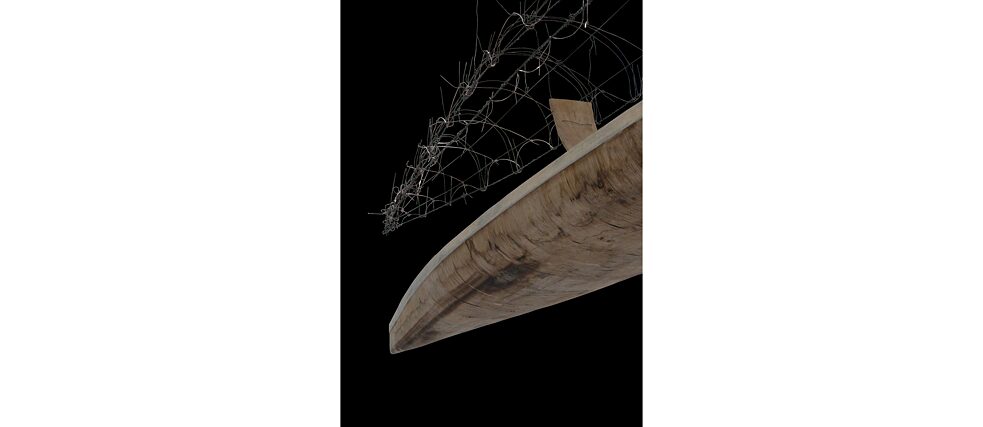

Jan Helda also explores the topic border. Helda has been living in Poland for 15 years. His sculpture can be regarded as the centrepiece of the exhibition in the Galeria Arsenał. A two-part canoe holds up the dichotomy of the two systems – Belarus and Europe – before our eyes. It seems as if we – and also Helda – don’t really have a choice which side of the boat we could choose: one half is made of wood; the other of barbed wire.

Information about the exhibition:

When The Sun Is Low The Shadows Are Long was shown from 01.04.2022 to 13.05.2022 at the Arsenał gallery in Białystok. Subsequently, the exhibition can be visited from 10.06.2022 to 25.09.2022 at the Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst (GfZK) in Leipzig.

This article was published first on 9th April 2022 in taz.