Art and Values Baltimore

Baltimore and the Arts

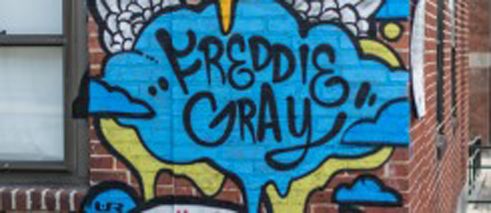

Since the violent death of Freddie Gray, the news from the city of Baltimore has been bad. The city is not unfamiliar with crisis, but there are also glimmers of hope. Now, the people want justice: a challenge for the judicial system, but also for the arts. Observations by Wilfried Eckstein.

Baltimore made the headlines last week with sad news and alarming images. The 25-year-old African-American Freddie Gray died after brutal treatment during a police arrest. Pupils demonstrated. Citizen protests escalated into rioting against businesses and police. A state of emergency was declared.

But there were also other images in the media: young people sweeping away the shards of glass the morning after the first riots, public libraries deciding to remain open for the people even near the neighbourhood of the rioting, Sandtown-Winchester. The director of the city libraries explained that the people need libraries to be safe places; places of refuge for families and the public. Other cultural institutions also kept their doors open. The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra played a free concert as conductor Marin Alsop declared her hopes that this would inspire others to try to change the world.

The protests have probably ebbed since the state’s attorney for Baltimore City, Marilyn Mosby, charged six police officers with murder and manslaughter. People on the streets of Baltimore, Washington and other US cities responded with honking, cheering and instantaneous marches.

For three decades, Baltimore has been known far beyond US borders for its high crime rates. Last year, the police made 60,000 arrests, a startling number considering a population of a little over 600,000. The TV crime series The Wire substantiated this negative image of the city.

Promising urban culture

But more and more artists are finding their way to Baltimore. Young people come here from other states because of the promise of reasonable rents and a vibrant urban culture. By no means are all neighbourhoods growing, but the city has always been a way station. These days, immigrants from the Middle East, Africa and South America come and are received by Baltimore’s welcoming culture, which basically changes nothing in the crisis of the city but certainly makes it more worth living in and loving.Until the late 1940s, the neighbourhood where Freddie Gray lived was home to the African-American middle class. The Royal Theater, where people heard and saw Duke Ellington, Billie Holliday, Eubie Blake, Chick Webb (a Baltimore native) and other jazz greats, is still nearby. That era is over. Today, one third of the inhabitants here live under the poverty line. For thirty years, the median household income has been 22,000 dollars. Nutrition is poor, every fifth adult is unemployed. Illiteracy, teenage pregnancies and drug abuse cast shadows over prospects of escape from the plight.

There are also other sides of Baltimore, beautiful sides. But no nook of the inner city has been left untouched at some point in time by grave crisis. The history of Baltimore is, nonetheless, quite splendid. In the nineteenth century Baltimore was the second-ranked immigration, seaport and industrial city in the United States. Today, magnificent skyscrapers, lovely mansions and colossal downtown structures are testimonies of the former heyday of this city of commerce and manufacturing. Then, in the 1950s, the city began the process of shrinkage that continues today. Over the past hundred years, the population dropped from 1.2 million to half that number. That was when urban sprawl began to take hold in American cities, when the middle class moved to the suburbs.

Charm, humour and perseverance

But over the past two decades, some parts of the city, such as the waterfront and the former industrial area near the train station and one that borders on Sandtown-Winchester, have been going slowly but measurably through an upward trend and out of permanent crisis. The facts remain the same, though: the jobs have not returned, people cannot feel statistical economic growth in their own pockets. So why are some neighbourhoods becoming safer?Last year, the Goethe-Institut Washington organized a cultural program about what is known as "creative placemaking". We and other European cultural institutes asked what positives the arts can contribute to an oppressive urban situation. What can dedicated citizens and artists do to make an urban area more resilient and find its way back to normal civilian life? We often asked ourselves whether we in Europe will be spared the kind of experiences taking place in Baltimore and how our societies at home can better prepare for the next crisis.

We learned a great deal in and from Baltimore. We met sculptors, painters, gallery owners, theatre makers, urban planners, investors and other dedicated people of Baltimore who will not give up on their city, who identify with it and are working to prevent its demise and bring about a renaissance. We learned how people can create a new culture of neighbourliness, how to make a park safer and a street walkable again. We understood that this dedication requires charm and humour as well as a perseverance that must be as relentless as the crisis it confronts.