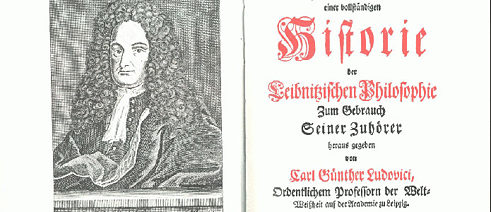

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

A Life for Science

Mathematics, physics, linguistics: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was at home in many disciplines. His work had a great influence internationally – albeit only after his death three hundred years ago.

“When I wake up in the morning I have got so many ideas in my head that the day is not long enough to write them all down,” said Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. The polymath could not have put it more aptly. Leibniz reflected widely on medicine, theology, politics, history, higher mathematics, technology, linguistics and physics. He also wrote down many of his thoughts; sometimes an envelope was sufficient to make a swift note. He published scarcely anything during his lifetime. Only after his death were his notes found: the amounted to about 200,000 sheets.

Leibniz devoted his whole life to science. He conducted research and exchanged ideas with scholars the world over. His insights and initiatives influenced many scientific disciplines and still have an impact today. Among other things he founded infinitesimal calculus – calculating with infinitely small numbers – laid the foundations for informatics, developed the binary code and studied the origin of words. The scholar called for scientific work to make use of sources and he is considered to be an important pioneer of the Enlightenment. Leibniz’s efforts to facilitate access to knowledge for as many people as possible was particularly progressive. He also encouraged the establishment of science academies for a better exchange of ideas between researchers.

“The last polymath”

Leibniz was born on 1 July 1646 in Leipzig. Today he is often designated as the “last polymath”, although competence in several different fields was not unusual in the 17t and 18th centuries. “Specialisation in individual study areas came later”, according to Harald Siebert, science historian at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences. “Leibniz may well have been an exception as regards the extent of his interests, the quantity of his notes and his originality, but at the time scientific research was strongly anchored in philosophy.”Leibniz started to study law at the age of 15, and did his doctorate at the age of 20. That was also not unusual. “When young men finished grammar school, they went on to study,” says Siebert. Six years after completing his studied Leibniz moved to Paris – and his sojourn there shaped his whole life. The French capital was the cultural heart of Europe at the time. Many scholars and scientists lived there. Leibniz got to know the Dutch mathematician and physicist Christiaan Huygens, among others. “Huygens recognised Leibniz’ talent and promoted him,” says Harald Siebert. “But he also noticed that Leibniz’ mathematical knowledge was not quite up to date and so he gave him the most recent publications. Leibniz worked through them all. For him it was like a second course of studies.”

Numerous trip throughout Europe

After four years in Paris, Leibniz accepted the post of Court Librarian in Hanover. His obligations there did not prevent him from making numerous trips around Europe. For years he sought in vain to return to Paris, but Hanover remained the centre of his life right up to his death. The local aristocracy may have had money, but had little appreciation of science and philosophy. “Leibniz felt very much alone. As he had no one to talk to, he maintained about 1,100 correspondences worldwide,” as Vincenzo De Risi, historian at the Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science, explains. “What is more, he had a huge library built in Hanover, because apart from those correspondences he had no other access to knowledge.” As Leibniz also made a copy of all the letters he wrote for himself, about 15,000 letters were found after his death.One of his most famous exchanges of ideas was with the English natural scientist Isaac Newton. The two researchers discussed the relationship between time and space in their letters. Newton was of the opinion that space was absolute. Subsequently a three-dimensional immobile space existed in which matter moved fully independently of it. Leibniz, by contrast, thought that space was relative, that matter defined it in the first place, and that everything in space was connected. Space was, moreover, always dependent on the observer. The correspondence with Newton was published shortly after Leibniz’ death and was read across Europe with great interest. Newton and Leibniz appeared to be adversaries. “The space-time discussion is still ongoing. To this very day, it still has an impact on the cornerstones of physics,” says De Risi. “In the correspondence of the two men Newton had more arguments, however, and Leibniz could not refute his physical explanation.” The arguments Leibniz was lacking were provided 200 years later by Albert Einstein in his general theory of relativity.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz died on 14 November 1716 in Hanover, and this year the anniversary of his death comes around for the 300th time. The year 2016 was therefore declared to be the Leibniz Year. Countless events related to the polymath are being organised not only in the city of Hanover, but also in institutions throughout Germany and indeed the whole world.