Non-European Art

“We don't want to be like you”

When do we classify something as a work of art?

Mona Suhrbier from the Weltkulturen Museum (Museum of World Cultures) in Frankfurt am Main is an expert on the Amazon and an ethnologist by trade. She explains why it is so hard for the work of rural, indigenous women to get into a museum, and why art experts should brave stepping outside their own familiar art world more often.

Ms Suhrbier, what kind of art would you classify as “indigenous art”?

I should mention at the outset that we don’t use the term indigenous art here at the Weltkulturen Museum, where we have been building our collection of contemporary, non-European art since 1975. Instead we name the specific region for each exhibition. But for a somewhat provocative answer to your question: indigenous art is everything that is not national art. It is the type of art countries don’t want the outside world to see as representative, the “folklore” and “arts and crafts”. Mexico is an interesting example. Mexican art has borrowed extensively from local indigenous traditions. Painter Diego Rivera, the internationally renowned figurehead of Mexican modernism, referenced local traditions, such as the cult of the dead. Yet although 80 percent of all Mexicans belong to an indigenous group, there is still a clear distinction made between what we might call “universal” art, the high art considered suitable for display in an art museum, and art that is seen as a type of folklore. In the 21st century, Mexico built a museum especially for folklore. I can’t help but wonder why. Why aren’t the works on display there just art?

Have you arrived at an answer?

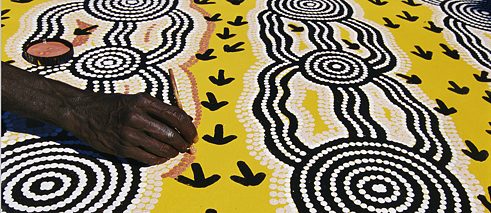

There is a tendency to put any work of art that uses rural forms of aesthetic expression into a folklore museum, especially if the artist was a woman. This is not the case for a male artist from an urban area like Mexico City. If he has the proper resume and studied with the right people for example, then - and only then – he is on his way to becoming a respected artist. I think “western” criteria are the problem here. Classification is often based on the material used. While the art world might accept that ceramics ‘might’ be art, a woven basket has a much harder time of it. Very little contemporary art from rural contexts makes it into our museums, though there are a few exceptions, like Aborigine and Maori art.

To what extent do art experts socialised in the western tradition reflect on whether they are even qualified to judge art from other, unfamiliar traditions?

I think everyone, even art experts, tends to judge the things they know as good. Most people don’t consider that they grew up in a specific visual world, and that this world serves as their guideline in a sense. It is more of a gut feeling than an intellectual approach. I think we don’t explore and question our own aesthetic imprinting nearly enough.

Even when non-European or indigenous art is shown in western museums, we rarely see or hear about the people who made it. Why is that?

It’s often a practical problem. Let’s say we are planning an exhibit in Frankfurt and invite a representative of what we might call the “source community” to attend. It would also make sense to invite an English-speaking representative from the academic field as well, someone who could reflect on the works and place them in context, making communication and understanding easier. Finding this person is like the proverbial needle in the haystack though. We try, but we don’t always succeed. Then there is the issue of defining the “source community” itself. I just finished setting up an exhibit of Guaraní artists. There are around 250,000 Guaraní people spread across five countries in South America. It would be impossible to select one representative.

So who did you invite?

A group of rappers, along with some others. The Guaraní people are poets and singers, and rap is a natural direction for young people to take today. One particular sentence the boys performed really spoke to me: “We don’t want to be like you”. This is how these young Guaranís are telling Brazilian society: we have our own ideas of how to live. For the indigenous peoples of South America, survival means each new generation has to find a new path. Otherwise they perish. Each new generation has to enter into dialogue with the respective national society, whether colonial or modern, and negotiate their lives. The young Guaraní are doing it now through rap.

As an ethnologist, what do you see as the biggest challenge for western art historians, gallerists and others in the field when dealing with non-European and indigenous art?

The art world has its own ideas and values, and can be tremendously naive in its judgments at times. Dealing with the foreign, the unfamiliar, takes practice. The western intellectual elite have not yet accepted that the world is big place with so many different schools of thought. You have to accept and respect that some art tells you: we don’t want to be like you. We want our art to be different and our rap too.